The Science of Science Communication

Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen · | Science Communication |In November 17-18, 2017, Bill Dennison, Suzi Spitzer and I attended the Science of Science Communication III, part of the Sackler Colloquia series of the National Academy of Science. The theme was “Inspiring novel collaborations and building capacity." This theme built upon two previous colloquia in 2012 and 2014, but focused on the consensus study report Communicating Science Effectively: A Research Agenda, in particular. The overall goal of the colloquium was to improve science communication by attracting new researchers and fostering institutional commitment to evidenced based science communication. This blog is the first of three blogs that will discuss this event.

Bill, Suzi and I first discovered the Science of Science Communication Colloquia series through the journal club that we started about a year ago. In this club we discussed many of the articles from the two PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Science) special issues that resulted from the two previous colloquia. All those papers had greatly informed and expanded our understanding of the science of science communication and how it can be informed by the Social Sciences. So, when we found about a third colloquium, we decided to attend.

The 2017 colloquium was held at the National Academy of Science in Washington DC. I was pleasantly surprised by the creative, science themed artwork inside. When viewing this artwork, together with the history and inherent prestige of the Academy, one can't help but be instantly inspired. The two-day conference brought together an impressive group of researchers and practitioners with the goal of advancing science communication and building capacity. Each day was filled with a combination of talks and panel discussions that were all live streamed and recorded. The two moderators, Mr. Frank Sesno and Mr. Ashley Llorens, did a great job in guiding the sessions. After each sessions, questions were taken from the physically present participants and from online participants who were engaged through Twitter (#SacklerSciComm). Awards for building capacity and partnership were also given out to two researchers-practitioners team, and their proposed research were presented and discussed during the colloquium.

The topics that were covered in the two days included genetics, health, business, driverless cars, and even immigration. The main points, though, remained the same:

1. There is a science behind effective science communication, and research is much needed. There is a greater need now than previously to effectively communicate science to the public. This led to the consensus study report Communicating Science Effectively: A Research Agenda, advocating for a framework to advance both the research and practice of science communication. While not all scientists are expected to get out in the public, those who do need training and a better understanding of what works and what doesn't work. Frequently emphasized was the importance in communication of story telling, framing the issues, and going "glocal," which is the idea that fundamentally, people accept things at the local level. People also gravitate towards stories. A great story is that of compelling characters overcoming obstacles to achieve a worthy outcome.

Forming interdisciplinary (and transdisciplinary) research teams is also essential in studying science communication. This in and of itself, though, is a challenge. Bridging gaps to make collaboration effective can be achieved through cognitive and affective integration and through healthy debate and deliberation among team members.

2. The science and the practice of science communication face multiple challenges and thus, the alignment of researchers, funders, practitioners and users is needed. Advancing the field of science communication is complicated by the traditional structure of academic institutions, the current complex media environment, the inherent controversy surrounding some scientific discoveries and applied technology, and other important issues such as scale and evaluation.

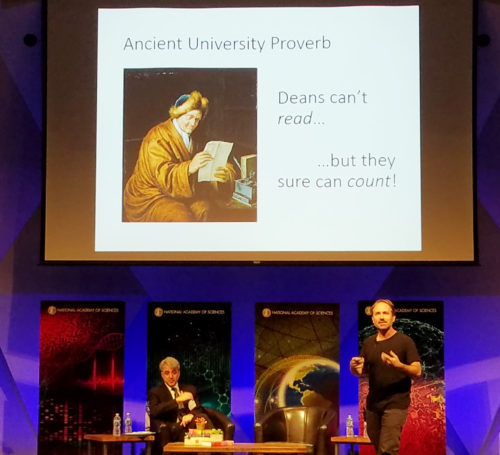

Although there are some academic and research institutions that encourage collaboration, extension, and stakeholder engagement, the biggest hurdle for researchers and especially for early career scientists to engage in inter/transdisciplinary work, aside from little funding and support, is the lack of incentives and opportunities within the existing academic rewards system that puts more value on peer-reviewed publications and disciplinary work. Another challenge in the incorporation of science communication in "main stream" science is the lack of a mechanism for evaluating its effectiveness.

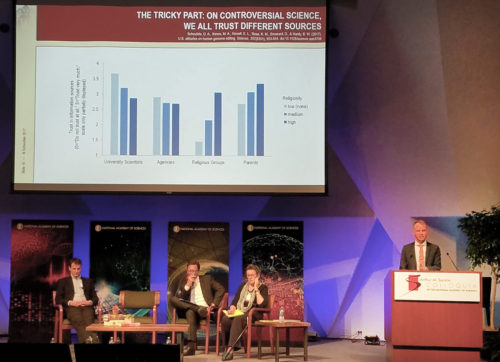

Today's complex media environment also poses a big challenge for researchers and practitioners who practice science communication. With the internet, it becomes easier to spread and share our research. However, the public is able to receive information from many different sources, some of which may report scientific findings incorrectly. Because of this tension, the biggest question is whether message is being heard and understood. Some of the controversial scientific issues in the media discussed in the colloquium included gene therapy and gene drives, artificial intelligence in driverless cars and infectious disease and vaccines. While there was not a session on communicating environmental problems and climate change, communication issues remain the same regardless of scientific field. Personally, it's been a while since I have attended talks on issues related to genetics and the biomedical sciences, so I appreciated and enjoyed those sessions.

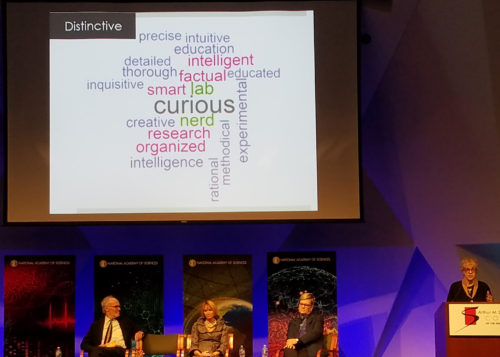

3. Scientist are "secretly human." This was the running joke throughout the colloquium, but the essence remains true. Being an effective communicator is an acquired skill and should be honed. Foremost is that scientists and researchers should "embrace" their humanity to have positive societal impacts. Suzi discusses this topic more in her blog.

4. There is mistrust of Science that needs to be addressed. According to the plenary speaker, Dr. Atul Gawande, this mistrust stems from two disputes: (1) a genuine debate about data and (2) whether scientists are trustworthy or not. Dr. Gawande shared his insights and experience as a surgeon, writer and public health researcher in how to deal with this "mistrust." Fundamentally, it boils down to how we do our science and what we think, and I quote, "we're battling not only what it means to be scientists but what it means to be citizens."

One of the greatest challenge in science communication is in communicating uncertainty. According to Dr. Gawande, in grappling with uncertainty, scientist explains the world by successive estimation. He gave the example that in the 19th century, one of the biggest issues in surgery was the use of anesthesia and antisepsis. Although both are good, their adoption rate at that time was not the same. Why? Because the effects of anesthesia are immediate and visible, and the effects of antisepsis are invisible. It's harder to convince people to change something that cannot be seen and for a reward that is not immediate. The same analogy can be applied for communicating uncertainty in climate and biological science. Dr. Gawande likened climate change to hypertension: both are considered silent killers.

Overall, the Science of Science Communication III Colloquium lived up to its promise. It's comforting to know that the importance of Science Communication is now being widely recognized and actively being advanced. Much of the themes that were discussed is also something that we are now applying in our own practice of Science Communication at IAN. Because there is still so much to learn and discover, it's very important for us to stay involved and evolved with this emerging field.

About the author

Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen

Dr. Vanessa Vargas-Nguyen is a Science Integrator with the Integration and Application Network and an associate faculty of the Marine Estuarine and Environmental Science Graduate Program. Her current interest is in transdisciplinary approaches, socio-environmental assessments, socio-environmental justice, stakeholder engagement, and adaptive environmental governance. Vanessa is originally from the Philippines and has extensive experience in molecular biology and marine science, specializing in microbial communities and molecular processes associated with Harmful Algal Blooms and shrimp, corals, and human diseases. She has since shifted her focus on how science can benefit society and was conferred with the first Ph.D. under the new Environment and Society foundation of the MEES graduate program. Her dissertation used ethnographic approaches to investigate the role of socio-environmental report cards in transdisciplinary collaboration and adaptive governance for a sustainable future. She received academic training from the University of the Philippines (BSc; MSc) and the University of Maryland (MSc; PhD). She is involved in developing holistic socio-environmental assessments for complex systems such as the Mississippi River and Chesapeake Bay watersheds and is coordinating a multi-year international transdisciplinary research consortium involving the US, Norway, Philippines, Japan, and India.