Towards improved understanding of human-environment interactions through cultural anthropology – building on the legacy of past scholars to overcome current challenges

Kirk Saylor ·Readings and discussion this week were led by postdoctoral fellow Elizabeth (Liz) van Dolah, a cultural anthropologist focused on the Chesapeake Bay region. Cultural anthropology comprises one of four fields within the discipline of anthropology, the other three being physical (or biological) anthropology, linguistics, and archaeology. Alfred Kroeber has been widely quoted for describing Anthropology as "the most humanistic of the sciences and the most scientific of the humanities." This description seems particularly true of studies conducted by cultural anthropologists concerned with understanding other societies, rather than missionizing, changing their customs, etc. Culture, however, we define this superorganic phenomenon (i.e. as a tool or social construct), seemed to generate interest among participants and provided a good foundation for the modules to follow.

Before launching into a formal discussion of cultural anthropology, an initial brief exchange concerned widespread wildfires across the western US and how to place fire in a cultural context (i.e. how it is viewed and used by societies). Having spent a decade in Australia earlier in his academic career, William (Bill) Dennison mentioned how traditional Aboriginal burning practices were suspended by land managers in areas designated as protected parks. This policy, in turn, altered vegetation patterns, and predator-prey dynamics, eventually leading to wild dogs (i.e. Canis familiaris dingo) opportunistically attacking and killing humans. Bushfires of increasing frequency and intensity pose a hazard to both humans and biodiversity/ecosystems.

On this topic, Kenneth (Kenny) Rose asked whether the group considered climate change the key factor in changing fire patterns. Although there is evidence of climate-fire teleconnections, he noted predisposing/proximate factors, such as forest management practices, "random" events (e.g. lighting),1 and "chance" events (e.g. gender reveal party), seen by others as more important. He suggested the complexity of such situations requires a coupled systems perspective accounting for multiple feedbacks. For more on the human fire use by Native Americans, n.b. Vale2 and Stewart.3

Shifting to the formal discussion slides on "Environmental and Ecological Anthropology" provided background/context to situate the assigned readings and facilitate discussion concerning how culture influences beliefs, values, and behaviors. The historical roots of anthropology as a discipline can be traced back to scholars from other disciplines, e.g. Darwin, Lyell, Malthus, and Ratzel. Two other scholars worth mentioning include von Humboldt and Darwin's contemporary Wallace.

The acknowledged "father of Anthropology." Franz Boas conducted pioneering studies of Native Americans in the Arctic and Pacific Northwest (Eskimo, Inuit, and Kwakiutl).4,5 Boas believed cultures need to be evaluated based on their unique history set within a given environment, and he, therefore, focused on gathering empirical data to inform deductive analyses grounded in cultural relativism and historical particularism. Boas' legacy has continued through his academic progeny, including Mead, Radin, and Sapir (among others), and their progeny in turn.

Boas' approach challenged the Eurocentric framework of inexorable "progress" from savagery to barbarism to civilization, e.g. per Morgan. While hunter-gatherer and pastoral nomadism livelihoods have become rare,6 there are still places where such "anachronistic" modes of living continue. It should be noted the disappearance of shifting cultivation from Europe ~ 250 years ago resulted from government efforts to assert control and promote modern agriculture.7

With regard to the assigned readings, Rappaport was considered first. His paper on the cultural regulation of human-environment interactions focused on the ritualized practices for the management of pig populations by the Tsembaga Maring in New Guinea.8 A question posed by students was whether Rappaport engaged with this population to obtain direct evidence via interviews/surveys. The published paper did not appear to provide any indication in that regard. However, Rappaport's doctoral dissertation and fieldnotes may offer further clues.

Another student posed a much broader question: could modern society be considered as existing "in balance with the ecosystem"? This led to the discussion concerning the extent to which the planet could be seen as a self-regulating system. On a geologic timescale, there are periods of relative stability but also catastrophic occurrences, e.g. major extinction events.9,10 Human activity over several millennia of the Holocene cased widespread megafaunal extinctions and biome-level transformations. More recent anthropogenic transformation of ecosystems are correlated with major declines and losses in biodiversity since 1970 CE.11

Rose cited the complexity and interdependency of supply chains, of which most people have been largely oblivious until the current pandemic, as an example of people's estrangement from natural resource systems on which they depend. Such data are however becoming more widely available thanks to NGOs, e.g. the Stockholm Environmental Institute and its "Transparency for Sustainable Economies" website, which provides insight into a variety of agricultural commodities (food, feed, biofuels, pulp).

Various criticisms have been raised regarding Rappaport's research for being overly functionalist, reductionist, materialist, and potentially environmentally deterministic. Additionally, Rappaport did not consider surrounding systems beyond the study area. A number of alternative frameworks emerged, per Biersak:12 symbolic ecology, with a focus on placemaking and cultural landscapes; historical ecology, with a focus on nature as historically produced; and political ecology, with a focus on the role of power asymmetries.

Further discussion of Rappaport involved questions of bias: Was Rappaport biased in his study? If so, what were the sources of bias? Could these be corrected? It was suggested that some anthropological scholarship had racist roots, but academic institutions have been working toward greater representation of ethnic and racial diversity. There was a sense that uncomfortable questions need to be asked within the scientific community, in order to move the discussion forward and overcome conceptual and practical barriers.

Question (1 of 3)

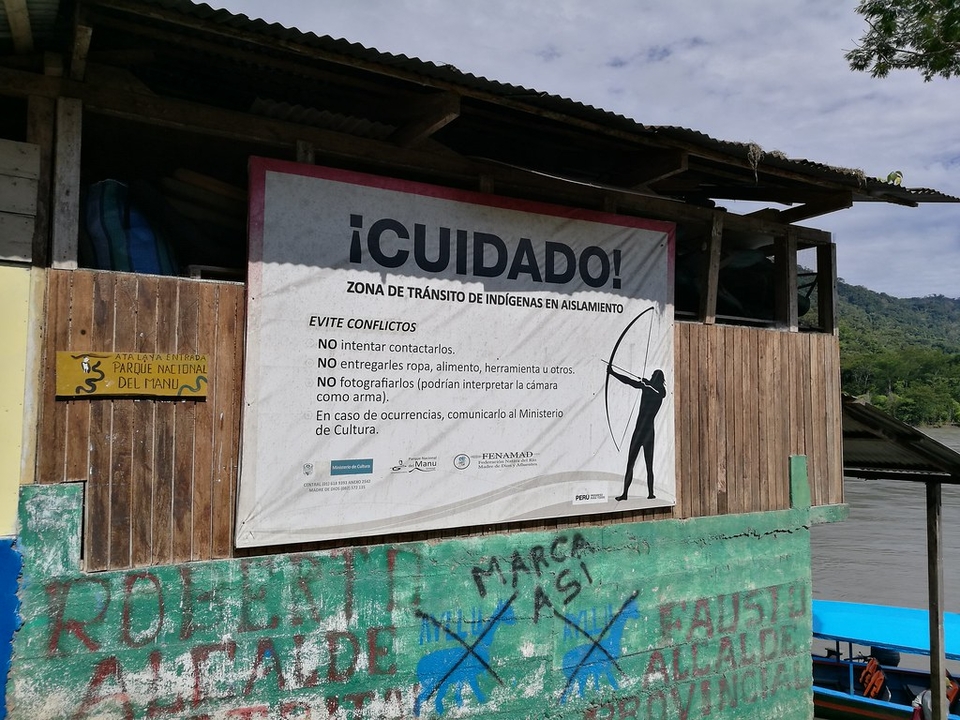

What can be done to effectively engage indigenous cultures regarding sustainable resource management, when native peoples are justifiably concerned about outsider intrusion in the context of the ongoing pandemic? Note the recent killing of Rieli Franciscato in Brazil in this regard?

Finally, the discussion turned to the Chesapeake Bay, which constitutes the area of interest for faculty leading this course as well as several students. The reading by Paolisso13 reflects the conceptual development of cultural anthropology beyond place-based frameworks. In practice, it acknowledges that communities have distinctive identities and intrinsic values, which are shaped to some extent through discourse between stakeholders. For communities whose livelihoods are based on natural resources, e.g. farmers and fishermen, it is important to keep such communities engaged with outside actors. To the extent that such groups are not properly included and engaged, regulatory processes would be more prone to fail.

There are a number of emerging issues in the Chesapeake Bay region that require collaborative engagement and involvement. One such issue that emerged in discussion was the proper management of tidal ditches in light of relative sea-level rise (i.e. net effect of subsidence and rising sea levels), which can be exacerbated by storm surges / tidal events. Another related issue is marsh migration and forest dieback (i.e. ghost forests), associated with changing salinity gradients. Such trends are relevant to at least one of the doctoral students doing research supported by NOAA.

Given the clear connection between climate change and recent/ongoing developments in the Chesapeake Bay, the discussion turned to the question of how to overcome climate change denial and disinformation efforts. It was suggested that faith communities need to be engaged more broadly than has been the case thus far, particularly majority white congregations that tend to lean right of center. Also, informational outreach efforts need to be - and are being - restructured to create more / better communication between scientists and citizens in affected areas.

On a broader level, Rose cautioned there needs to be a clear line of separation between science and policy, whereby scientists avoid explicitly advocating in such a way that they would appear to be activists. This viewpoint was communicated by Nancy Baron, who refers to Advocacy as the "scarlet letter" of academia in her op-ed in Nature14 and book.15

At the same time, it warrants noting that the federal government has been pursuing a rather overtly anti-science agenda over the last few years, including but not limited to climate change denial. The recent appointment of an industry-sponsored climate skeptic to a senior government position, along with other efforts undermining regulations related to air quality and water quality, as well as failures to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, raise major environmental concerns. Given unprecedented current circumstances, it does not come as a great surprise that certain arbiters of science feel compelled to weigh in on upcoming elections, e.g. Scientific American.

Question (2 of 3)

What would you consider the threshold for science to assert position vis-Ã -vis the need for change in governance? Or must scientists always remain neutral to "maintain objectivity"?

Brief addendum - Cronon (1996)

As a brief addendum, this blogger wishes to mention briefly the recommended reading by Cronon16 for its discussion of human-constructed "nature" spaces across California. Additionally, Cronon provides a relevant analysis of socially constructed wilderness since the time of Muir, whereby an ideal of pristine nature has assumed the status of a secular religion. Nature as either a "lost Eden" or "avenging angel" both seem to be fairly compelling social constructs in the present era. To the extent that wilderness becomes idealized as nature-without-humans, it does not provide a space within which humans can exist. Cronon, therefore, challenges the relatively extreme views of the Deep Ecology movement, arguing for a middle ground position of human coexistence.

Question (3 of 3)

What would you consider to be a culturally viable "middle ground" for regulating human values and behavior vis-Ã -vis the environment per Cronon's conclusion to Uncommon Ground in a contemporary consumer society (e.g. U.S.)? From a practical standpoint, what constitutes a middle ground position vis-Ã -vis dependence on fossil fuels, factory farming, waste management, and/or other societal problems associated with capitalist systems of production?

Thanks to the faculty for leading this discussion and everyone for their participation. Any errors or omissions are my own. Would welcome any additional reflections that you may have to offer on this discussion.

Works cited

1. Abatzoglou, J. T., & Williams, A. P. (2016). Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(42), 11770-11775. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607171113

2. Vale, T. R. (Ed.). (2002). Fire, native peoples, and the natural landscape. Island Press.

3. Stewart, O. C., Lewis, H. T., & Anderson, K. (2009). Forgotten fires: Native Americans and the transient wilderness. Univ Of Oklahoma Press.

4. Boas, F. (1896). THE DECORATIVE ART OF THE INDIANS OF THE NORTH PACIFIC COAST. Science, 4(82), 101-103. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.4.82.101

5. Boas, F. (1889). The houses of the Kwakiutl Indians, British Columbia. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 11(709), 197-213. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.00963801.11-709.197

6. Heinimann, A., Mertz, O., Frolking, S., Egelund Christensen, A., Hurni, K., Sedano, F., Parsons Chini, L., Sahajpal, R., Hansen, M., & Hurtt, G. (2017). A global view of shifting cultivation: Recent, current, and future extent. PLOS ONE, 12(9), e0184479. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184479

7. Dove, M. R. (2015). Linnaeus' study of Swedish swidden cultivation: Pioneering ethnographic work on the 'economy of nature.' AMBIO, 44(3), 239-248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0543-6

8. Rappaport, R. A. (1967). Ritual Regulation of Environmental Relations among a New Guinea People. Ethnology, 6(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.2307/3772735

9. Barnosky, A. D., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S., Wogan, G. O. U., Swartz, B., Quental, T. B., Marshall, C., McGuire, J. L., Lindsey, E. L., Maguire, K. C., Mersey, B., & Ferrer, E. A. (2011). Has the Earth's sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature, 471(7336), 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09678

10. Rosenzweig, M. L. (n.d.). On the evolution of extinction rates. 13.

11. Vitousek, P. M. (1997). Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems. Science, 277(5325), 494-499. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5325.494

12. Biersack, A. (1999). Introduction: From the "New Ecology" to the New Ecologies. American Anthropologist, 101(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1999.101.1.5

13. Paolisso, M. J. (2006). Chesapeake environmentalism: Rethinking culture to strengthen restoration and resource management. Maryland Sea Grant College, University of Maryland.

14. Baron, N. (2015). Science communication: In the cross hairs of controversy. Nature, 528(7582), 332-332. https://doi.org/10.1038/528332a

15. Baron, N. (2010). Escape from the ivory tower: A guide to making your science matter. Island Press.

16. Cronon, W. (Ed.). (1996). Uncommon ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. Norton.