Walt Whitman and The Celebration of Nature

Claire Sbardella · 2 comments I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

This is how Walt Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself” begins. With 52 sections, it is the longest poem in his book Leaves of Grass, and it is considered to be his most influential work. First published in 1855, critics consider both the poem and the overall books as American classics, and they remain extremely influential on poetry even today. It took several years before it was recognized, however; because of its use of blank or unrhymed verse and its sometimes salacious content it was almost refused publication. These two excerpts that I have chosen demonstrate some aspects of how the book, despite its original poor reception, is very well written, and maybe even more important to read today.

Unlike the poem that I analyzed last month, which contained a sobering environmental message and a clinical examination of disease, “Song of Myself” focuses on the celebration of nature and humanity’s place within it. Whitman is not separate from the earth, rather he embraces it. I think that taking a glance at his feeling of unity with the environment around him can remind us of the reasons we struggle to maintain and facilitate its survival.

The first section continues in the same vein as the first three lines:

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form'd from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their

parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

Creeds and schools in abeyance,

Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten,

I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard,

Nature without check with original energy.

The stream of consciousness style can make this poem somewhat difficult to follow, but it is a vital part of understanding the overall theme. Outdated words and spelling give modern readers an extra challenge. “Loafe” is an older spelling of the word “loaf,” which means to laze around. The word “abeyance” means “a state of not happening or being used at present" (link). Both of these words suggest a state of complete relaxation and ease. Stream of consciousness, with its free association of thoughts that have no formal introductions, enhances this mood. The poet’s thoughts shift naturally, from his feeling of unity to his personal life to the acknowledgement of his failures. Everything that he "harbor[s] for good or bad" are at one with the environment around him.

This idea of unity is explored further when Whitman asks his soul to join him in noticing a “spear of summer grass." This introduces a spiritual element to the poem, and emphasizes the fact that Whitman wants to be fully present for his meditation, “My tongue, every atom of my blood, form'd from this soil.” The grass that Whitman observes stands as a symbol of the small and overlooked becoming huge in meaning, an idea that is explored further in the poem excerpt below.

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also my brothers, and the women

my sisters and lovers,

And that a kelson of the creation is love,

And limitless are leaves stiff or drooping in the fields,

And brown ants in the little wells beneath them,

And mossy scabs of the worm fence, heap'd stones, elder, mullein and

poke-weed.

This final verse that I have included expands on this idea of unity and further focuses on what the author considers to be its underlying fixture of the world: love. The repetition of "and," is a stylistic device called anaphora, which is commonly used in hymns of praise. This stylistic shift from stream of consciousness to hymn stresses the unity of humanity, nature, and the divine. This joyful mood is enhanced by the poet's declaration that “the kelson of creation is love.” A “kelson” is a “centerline structure running the length of a ship and fastening the transverse members of the floor to the keel below" (source). It holds the ship together, just how love holds all of creation together. This abstract discussion is balanced by concrete images of leaves “stiff or drooping,” “brown ants,” “heap’d stones,” and weeds. These particular objects and animals are not commonly considered beautiful or noteworthy, but they are indispensable and meaningful.

“Song of Myself” is a literary classic, and I hope that my brief introduction to this poem will help you understand why I think that it still has much to offer. Despite the age of Leaves of Grass, Whitman’s reminder that we are intimately involved with nature stresses the importance of environmental protections – not only for the economics of survival, but also for emotional and aesthetic sustenance.

Poem text taken from Project Gutenburg

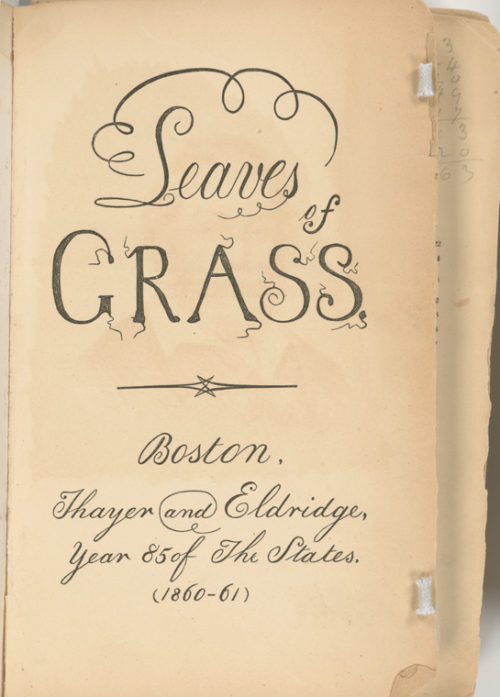

LeavesOfGrass Thayer Eldridge NYPL, by Thayer and Eldridge, licensed by Public Domain

Phytolacca-americana-berries, by Gerhard Eisner licensed by GNU Free Documentation License

The Cheesewring, by Mick Knapton, licensed by CC Attribution 3.0 Unported

Tragus roxburghii W IMG 1725, by J.M. Garg, licensed by CC Attribution 3.0 Unported

Next Post > Exploring an Ecosystem in Transition: On the Road to Flamingo II

Comments

-

Don Mcauly 8 years ago

pretty valuable stuff, overall I think this is really worth a bookmark, thanks

-

Lisa Becker 3 years ago

Thank you so much for this very clear introduction to Whitman! I plan to use your article in my American Literature class where kids are still trying to outgrow pandemic-related abeyance, lol.