To get the grade: Collaborate! Stakeholder engagement and the missing link between research and action

Veronika Leitold, Alec Armstrong ·Veronika Leitold, Alec Armstrong

An international activist, a fly fisherman, an NGO manager, a food & beverage consultant, a water quality researcher and an indigenous elder are all gathered around a table… Why? They have come together to make a decision: either approve or veto the construction of a new hydroelectric dam upstream in the river basin that is home to all of them. There is much tension between the proponents of the new energy source and the conservationists in the group. But with the recent forest fire that swept across the region mobilizing all available resources to control damage, these members of the community learned that only through coordinated effort and integrated action are they able to effectively safeguard their environment. Therefore, after carefully weighing the pros and cons, the group decides to veto the dam construction, thus evading the displacement of an indigenous village from the forested upper valley and maintaining the integrity of the community and the ecosystem.

The above story is only hypothetical and somewhat simplistic in nature. Yet, it models a plausible real-world scenario, which was based on the WWF’s interactive board game called “Get the Grade!” that we used as a tool in our Coupled Human and Natural Systems class last week to explore the topic of engaging stakeholders – i.e. people or organizations that have a legitimate interest in a project or entity, or would be affected by a particular action or policy – and the role of environmental report cards in guiding stakeholder decisions.

![Stakeholder engagement can be described as a process of maturity: each step of the process includes progressively greater participation from stakeholders and increasingly more shared responsibility with the management authority. Meaningful stakeholder engagement depends on the ability of practitioners to use the appropriate techniques in each successive step towards building a healthy, lasting, and trustful relationship with stakeholders. Source: Walton et al., 2013 [pdf] Stakeholder engagement can be described as a process of maturity: each step of the process includes progressively greater participation from stakeholders and increasingly more shared responsibility with the management authority. Meaningful stakeholder engagement depends on the ability of practitioners to use the appropriate techniques in each successive step towards building a healthy, lasting, and trustful relationship with stakeholders. (Source: Walton et al., 2013.)](/site/assets/files/2637/image1-500x172.png)

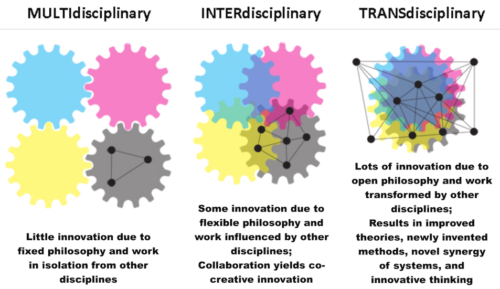

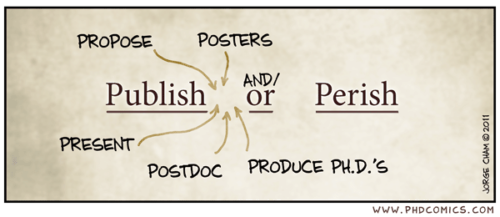

Following the hands-on session of Get the Grade!, the second half of our class took on a more theoretical tone as we reflected on ways in which collaborative research, stakeholder engagement and public outreach might fit into a scientist’s working life. The assigned readings for this week questioned many of the traditional academic and institutional norms, which hold that scientists are trained to provide information as “experts in their field,” they share knowledge through one-way communication by writing papers and giving talks, and their main motivation in the academic race for tenure and promotion is to improve their publication record (“publish or perish”). Stakeholder engagement is an inherently different approach, however, which consists in the co-development of the information gathering process between scientists and stakeholders, openness to the perspectives of others, and a shift in motivation from publication to creating public action. As such, it has much in common with transdisciplinary research.

Often, the problems we face in our modern-day society are complex, and they are best solved by applying transdisciplinary research elements, such as effective communication and leadership, intense collaboration, and the integration of multiple knowledge streams and value systems. In the field of conservation science, for example, it has even been suggested that “a conceptual paradigm shift should take place in the academic conservation discipline toward more commitment on the part of the researchers to turn conservation science into conservation action” (Arlettaz et al., 2010). But how can this be incentivized if academics are essentially evaluated on their research performance, i.e. their publication record, and not rewarded for any commitment to action and implementation in the current system? How much agency should scientists have in transdisciplinary collaborations? Can collaborative work and public outreach be considered as legitimate scientific output? Who is to decide?

The resounding consensus in our class discussion was that even if we can agree that engagement and public outreach should be part of our science careers, such roles require lots of time and effort, yet they remain undervalued in academia, therefore scientists are hesitant to engage in these activities, seeing them as mere distractions from the scientific productivity. There is a real value, however, in effective data synthesis and interpretation, and a growing demand for “knowledge brokers” who can facilitate transdisciplinary problem solving and action-oriented research by mastering “the art of communication” and bringing people together to collaborate. Perhaps not every scientist is fit for such a role, but the power of choice to transcend disciplines and think outside the academic box should be granted to everyone.

REFERENCES:

- Arlettaz R., Schaub M., Fournier J., Reichlin T. S., Sierro A., Watson J. E. M., Braunisch V. From Publications to Public Actions: When Conservation Biologists Bridge the Gap between Research and Implementation. BioScience 2010; 60 (10): 835-842.

- Boyer E. L. Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Chapter 2: Enlarging the Perspective. p 15–25. Princeton University Press, 3175 Princeton Pike, Lawrenceville, NJ, 1990. [pdf]

- Dennison W.C. Environmental problem solving in coastal ecosystems: A paradigm shift to sustainability. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, v 77, n 2, p. 185-196, 2008.

- Longstaff B.J., Carruthers T.J.B., Dennison W.C., Lookingbill T.R., Hawkey J.M., Thomas J.E., Wicks E.C., Woerner J. Integrating and Applying Science: A handbook for effective coastal ecosystem assessment. Chapter 4: Communication strategy: packaging and delivering the message for maximum impact, p 45–58. IAN Press, Cambridge, MD, 2010.

- Walton A., Gomei M. and Di Carlo G. Stakeholder Engagement. Participatory Approaches for the Planning and Development of Marine Protected Areas. World Wide Fund for Nature and NOAA—National Marine Sanctuary Program. 2013. [pdf]

Next Post > Atlantic Estuarine Research Society meeting at St. Mary's College of Maryland

Comments

-

Alec Armstrong 7 years ago

I think it could be interesting to explore changes to the game that promoted failure. This could be a follow-up or advanced round for people already familiar with the game and could be useful if it actually illustrated pitfalls. Examples of these changes include an alternative reward system that affected individual dice, the ability to punish other players or otherwise affect their ability to participate in decision or vote actions, cards that allowed players to make choices that increased their dice scores at the expense of a chosen value's dice, the ability to obfuscate information or distribute information about a decision or vote differently to different players, power differences like some values not getting votes or getting veto power, some kind of competition or scarcity, having 2 different teams playing simultaneously in adjacent basins or representing competing coalitions, etc.

-

Kelly Hondula 7 years ago

Veronika did a nice job of synthesizing both what happened during the game and our discussion of challenges to transdisciplinary research in academia. I think it would be an interesting twist to the game if different roles/characters had a different balance of how important the overall grade was to them versus their own individual performance. The rules of the game gave us that the goal was for us as a team or sub-basin to have the highest grade, but I think that in real life that may not always be the case or at least very challenging outcome to achieve. This is reflected somewhat in the second part of our class discussion, which elucidated the competing goals that people in different roles within academia have. Maybe this is also reflected in the game in that we didn't have anyone in the role of a graduate student or professor (although there was a water quality researcher).

-

David Miles 7 years ago

This topic is very interesting. I think the core academic practice of publish or perish is going to be very difficult to uproot and change. I like the idea of a go between, a knowledge broker as Veronika put it, bring people together to work on the complex problems bred from environmental issues. Perhaps a new "field" of scientist is needed, or maybe these issues can be taken up by other institutions besides those of higher learning, or maybe institutions of higher learning can make room for these types of research projects outside of the various disciplines that contribute to them. Perhaps this new field could publish papers about their successes and failures and those works be considered "publishing".

-

Killian F 7 years ago

Great job with the blog post! I like Suzi’s comment on universities being very supportive of students that are double majoring can help lead to changes in academia being more supportive of transdisciplinary work. While working on my double major at UMD, the two departments I worked with (Biological Sciences and Atmospheric and Oceanic Science) were both supportive, but had very little overlap in topics and requirements for both majors weren’t very flexible to allow for someone studying in two pretty different departments. Students in both departments were often surprised and confused to learn that I had a double major with the other department, though they could see how they could be applied together for interdisciplinary research. I think schools have a few majors that are used to people have double majors in together, but having people who are outside of established boxes of what majors work together can still lead to problems. Schools still have a ways to go to be fully supportive of transdisciplinary research for people at all stages of their academic career.

-

W.Cruz 7 years ago

Agreed with Rachel and Noelle we did change our strategy to get a better grade but we did not approve some regulations that could have benefit in a real world scenario but with this games we knew its outcomes so we played only to get a better grade.

-

Natalie Yee 7 years ago

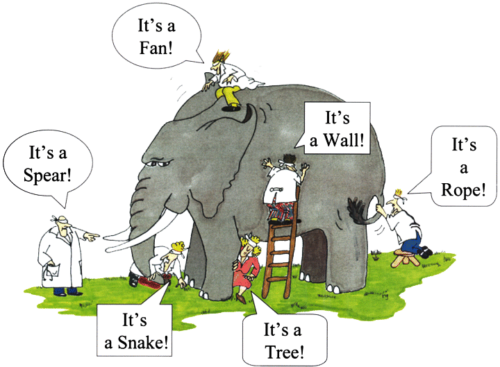

I agree with Rebecca in that that last image is a perfect example of how different stakeholders all have a valid point in their own sphere, but to make an informed decision, we have to look at the bigger picture to understand what is going on and where to go from here. This is directly reflective of how our Get the Grade session went. Although there was our own party interest in mind (economist, ecologist, politician, etc.), we realized it was the overall grade of the town that mattered in the long run. We took chances that potentially jeopardized some categories to better others because the entirety of the dam community was most important.

Having the ability to know the outcomes of the decisions for the second and third round created a different game play. The first round was much more own party centered, but knowing the effects allowed us to work together to better the whole community. The ideal goal is to be able to have stakeholders in real life to understand what the overall effects of decisions would be so that we can work together for the greater of the community, not just for our own parties.

-

Rebecca Wenker 7 years ago

I love the last image you used, and think it perfectly describes how a one-track focus and a lack of communication can really hinder progress. However, like you (and the previous commenters) have mentioned, the current academic system makes it somewhat difficult and unappealing to collaborate. It doesn't foster any reward for doing so. I wonder how this system could be altered to more easily promote beneficial collaboration, action, and translation of information to the public? How could collaboration be framed so that it benefits both parties, and the parties funding them?

-

Noelle O. 7 years ago

I agree with Suzi that there is a trend in academia to move towards trans-disciplinary educational training and programs, but it is still not the norm. I think stakeholder engagement is absolutely critical to fisheries and natural resource management. Management risks wasting a lot of time, money, and energy where there are large disconnects between scientists, managers, and stakeholders.

As Rachel mentioned, we were quick to change our strategy to have the overall highest grade rather than having our sectors come out on top. Ideally, management and stakeholder processes would follow this strategy and vote for decisions which would benefit the system as a whole rather than achieving individual victories.

I also love the comic at the end! An easily digestible reminder why communication is so important!

-

Suzi Spitzer 7 years ago

Great recap of our class activity and conversation! I especially enjoyed our discussion of various institutional barriers that discourage (or at least fail to encourage) academics who invest time and energy into stakeholder engagement and transdisciplinary research. As you mentioned, although community engagement and transdisciplinary collaboration are very useful strategies for solving complex problems, there is very little professional recognition for academics and professors who choose to use these approaches.

It is also worth noting that graduate students are often burdened by policies and requirements that tend to pigeon-hole us into one area of study—programs that encourage transdisciplinary work are springing up, but they are the exception! Perhaps a sign of changes to come is that more and more undergraduates are double-majoring in college and integrating various areas of study in order to tackle problems in new ways. Many universities have been extremely supportive of students who choose to double-major. Maybe this strategy will “trickle up” and lead to changes in graduate programs and academic departments, so that these institutions can eventually play a more supportive role in graduate student and faculty transdisciplinary research. -

Rachel E 7 years ago

Loved this blog Verokika! You really captured the events of the game well. The one different I think between this game and the "real world" is that all of us were interested in getting the best grade possible and not having other group members fail. It was sort of a group mentality that we wanted to all succeed. However, in the "real world" this isn't always the case and not all stakeholders will be sympathetic to the "indigenous elder."

If all stakeholders were aware of the grade and benefitted from having an overall good grade, then I think we could make a lot more progress towards making the grade better.

The last image you included describes this perfectly. People only see the solution that fits their stakeholder group, and not the over arching ecological problem. Well written!

-

Krystal Yhap 7 years ago

This was an amazing blog post Veronika! You did an awesome job capturing what we covered in our discussion, during game play, and in the readings we had for last week. My sentiments about our discussion in class last week and about this blog post are very similar to Suzi and Rebecca's. I would add that when we played the game everyone in our collaborative group started out by looking after their own interest and what decisions would benefit their particular sector. But as the game went on it seemed that slowly but surely our whole group began to start thinking more about the common goal, which was to get the best possible grade, and we started to make decisions based on what was needed to achieve that goal. This allowed us to get to know one another better, learn from each other, offer insight, and understand what type of action was needed in order to help the group advance as a whole rather than just our individual sectors. Like others have mentioned, sometimes this plays out well in real life and sometimes collaboration in real life is more time consuming and underappreciated and some stakeholders approach collaboration only looking at what it will do for them and what they bring to the table, rather than what can be learned from one anther. I love all the graphics you used to depict the different themes we discussed in class. The last graphic showing how if everyone focuses on their epistemology and that their knowledge base is the only one of merit that truly matters during a collaboration then you can completely miss the broader problem and potentially good solutions to that problem. Communication is so important and adopting a mentality of approaching collaboration as both a teacher and learner, respecting and seeking to understand everyone's backgrounds in order to collectively come up with ways to reach a common goal.

Like Suzi, I hope to see a change in the way academia, especially graduate programs, are set up and able to foster and encourage students to pursue more transdiciplinary work. I hope it is something that only increases in value both in and outside the academic community.