A Long Love Affair With Chesapeake Bay Part I

Bill Dennison · | Science Communication |Love, fifteen, thirty, and forty are tennis scores, but they also represent my relationship with Chesapeake Bay.

On November 29, 2017, I gave a presentation at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum (CBMM) as part of a four-part series about the Chesapeake photographer Robert de Gast (1936-2016). Through April of this year, CBMM is exhibiting 80 photographs curated from more than 10,000 by de Gast in their collection. My talk was titled “After de Gast: The Chesapeake transformation since 1972,” and included a discussion of three major storms that affected Chesapeake Bay, as well as various science and management advances surrounding the Bay. While developing a timeline of major Chesapeake events since 1972, I began to realize just how important my personal relationship with Chesapeake Bay has been throughout my career.

I began my presentation with cultural references from 1972 such as The Godfather, The Brady Bunch, the Ford Pinto, and Pong. 1972 was also a tumultuous year politically, with the terrorism attack on Israeli athletes at the Summer Olympics in Munich, and the Watergate hotel burglary of the Democratic National Committee that led to the impeachment of President Richard Nixon.

A significant Chesapeake science advance in 1972 was the launch of the Landsat 1 satellite which provided synoptic images of the entire Chesapeake Bay. The most significant Chesapeake management advance in 1972 was the passage of the Clean Water Act which provided the newly created Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) with regulatory authority over discharges into navigable waters. The Center for Environmental and Estuarine Studies, now University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, was also formed in 1972 by consolidating the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory (formed in 1925), the Natural Resources Institute and the newly created Horn Point Laboratory.

But the most significant event in 1972 for Chesapeake Bay was Hurricane Agnes. This very early storm (June 14-23) created flood conditions and was devastating for five states that were declared disaster areas and was also devastating for Chesapeake Bay ecologically. In particular, submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) were significantly reduced. Hurricane Agnes arrived after a very dry period in the 1960s and ushered in a relatively wet period in the 1970s. Agnes stimulated a suite of coordinated scientific studies that resulted in a book that described the extent and impact of Agnes on Chesapeake Bay, The Effects of Tropical Storm Agnes on the Chesapeake Bay Estuarine System, published in 1976.

In 1977, the EPA funded a suite of scientific studies to understand some of the transitions that were occurring in Chesapeake Bay. This was also the year that I first visited Chesapeake Bay aboard the R/V Westward as a Sea Semester student. We actually stopped at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, as we sailed from the mouth of the Bay up through the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. I was impressed with the vastness of the Bay as well as the people I met on Smith Island, in Annapolis and St. Michaels during our port calls. When James Michener published his 1978 classic Chesapeake, I avidly read it in my Alaskan cabin as I was doing my Masters research at the University of Alaska the following year.

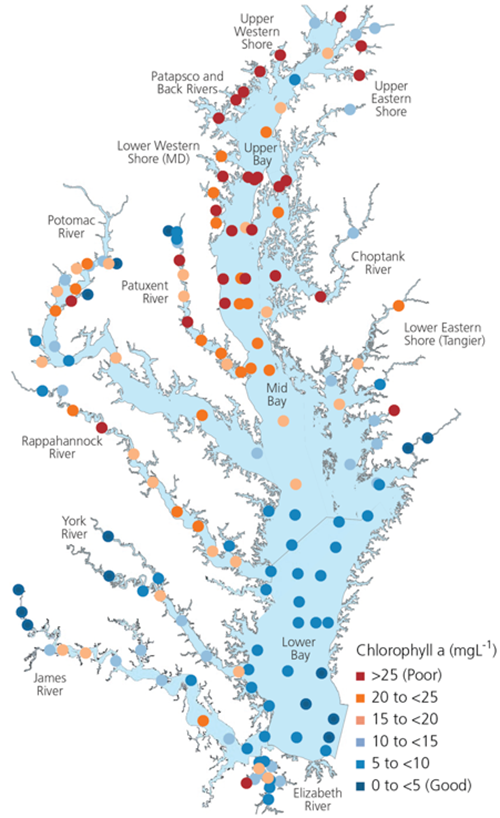

Several other important changes in Chesapeake Bay monitoring occurred over the next several years. In 1978, a large physical model of Chesapeake Bay was constructed in a huge warehouse on Kent Island. It has since been replaced by computer models, but it was an iconic tool. In 1983, the Chesapeake Bay Program was formed as a partnership between the federal government, Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia and was located in Annapolis. In 1984, the newly created Chesapeake Bay Program initiated a Bay-wide monitoring program, which still exists today. In 1985, a phosphorus detergent ban led to reduced phosphorus inputs into the Bay. Also in 1985, a five-year moratorium of striped bass or rockfish was instituted, resulting in a dramatic recovery of this iconic species.

in 1987, a Chesapeake Bay agreement was signed to reduce nutrients by 40%. This was timely since low oxygen bottom waters (“dead zone”) began to become prominent in Chesapeake Bay. Tom Horton published his classic “Bay Country” in 1987. It was also the year that I returned to Chesapeake Bay by joining the Horn Point Laboratory faculty for a four year stint. I was living on a boat, so when I arrived in Chesapeake Bay, it was via the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, where I had exited the Bay a decade earlier.

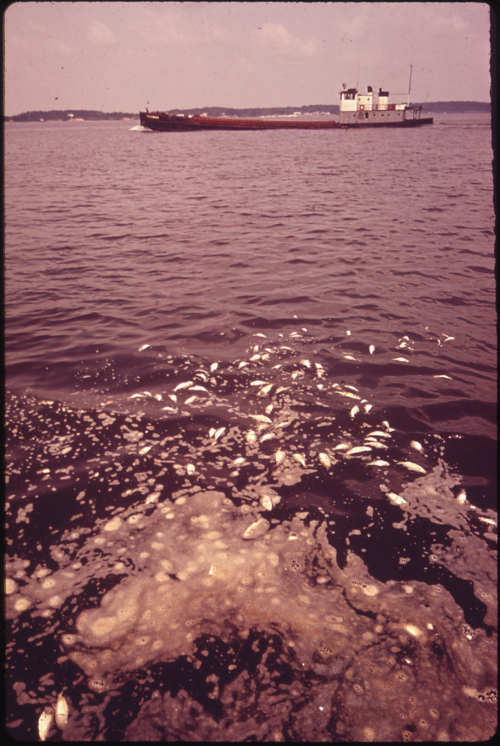

Twenty years ago, in 1997, mysterious fish kills with lesions were observed in the Pokomoke River. Human health impacts were reported by watermen which led to a media circus which resulted in a book called When the Waters Turned to Blood, by Robert Barker and a film (The Pfiesteria Files by Michael Fincham). The Delmarva chicken industry was implicated as a contributory factor in the algal blooms that led to the fish kills. In the year 2000, The Renewed Agreement called for water quality improvements. This led to the removal of Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries from the impaired waters listing by 2010.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.