Ancient culture and unique biodiversity - Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia

Jane Hawkey ·On May 22 and 23, Heath Kelsey and I had the opportunity to travel to Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory, the “top end” of Australia. The park covers some 20,000km2, making it Australia's largest national park. Our site visit provided the context for the project we were visiting Charles Darwin University for - to help synthesize and communicate the key findings of the National Environment Research Programme (NERP) scientists studying the Kakadu floodplains.

Kakadu was declared a National Park in three stages between 1979 and 1991, and is included on the list of World Heritage places for both its cultural and natural importance. There are also 683,000ha of Kakadu wetlands that are listed in the RAMSAR protected wetlands of international importance.

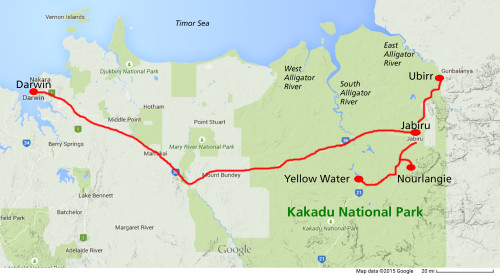

Starting at the city of Darwin, we drove 255km across the park to the town of Jabiru – our headquarters for two days of exploration of Kakadu. The region was in early dry season (May-Oct) with the wet season (Nov-Apr) floodwaters receding back to the deepwater rivers and billabongs (wetland lakes), becoming refugia for many plant and animal species.

Kakadu is a living cultural landscape. Many of the rangers are local Aboriginal traditional owners. Generations of Bininj/Mungguy have lived on and cared for this country for tens of thousands of years. The rock art represents one of the longest historical records of any group of people in the world. Their ancient history is evidenced by the fascinating rock art at Ubirr.

Aboriginal people have conducted traditional patch burning for tens of thousands of years. The ancestors gave them a cultural obligation to look after and clean up the land, a duty handed down from generation to generation. Done in cooler weather (early dry season) to prevent wildfires, huge benefits were gained as biodiversity was recovered.

En route to Jabiru, there were several areas along the road that were on fire. These are prescribed burns conducted by park management to clear the understory of grasses and small trees – potential fuel during the peak dry season. The smoke was attracting whistling kites (Haliastur sphenurus), medium-sized raptors that feast on the small mammals, reptiles and insects attempting to escape the blaze.

“This earth, I never damage. I look after. Fire is nothing, just clean up. When you burn, new grass coming up. That means good animal soon, might be goanna, possum, wallaby. Burn him off, new grass coming up, new life all over. - Bill Neidjie, Bundj Clan

Kakadu is home to 68 mammals (almost one fifth of Australia’s mammals), more than 120 reptiles, 26 frogs, over 300 tidal and freshwater fish species, more than 2,000 plants and over 10,000 species of insects. It provides habitat for more than 290 bird species (over one third of Australia’s birds). Some of these species are threatened or endangered. Many are found nowhere else in the world.

At Nourlangie, we hiked around the Anbangbang billabong, a seasonal wetland that was a great place to view birdlife.

About one third of Australia's bird species are represented in Kakadu National Park, with at least 60 species found in the wetlands. The South Alligator River system is the largest in Kakadu and contains extensive wetlands that include river channels, floodplains, and backwater swamps. We took a boat tour of Yellow Water, a large billabong in that system. Dawn proved a great time to see a variety of birds and saltwater crocodiles before the mid-day sun heated things up.

Our two days of exploration were much too short. It is an amazing place. The quote by Jacob Nayinggul of the Manilakarr Clan sums it up:

“Our land has a big story. Sometimes we tell a little bit at a time. Come and hear our stories, see our land. A little bit might stay in your hearts. If you want more, you can come back…”