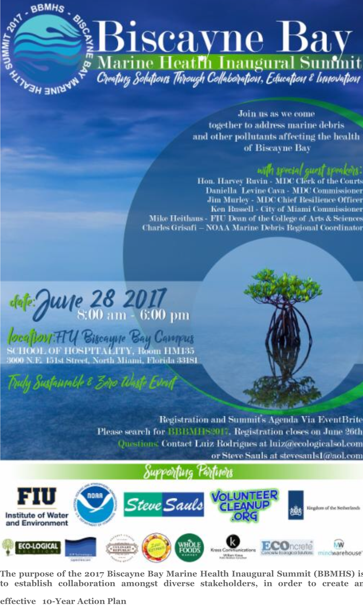

Biscayne Bay Marine Health Inaugural Summit

Bill Dennison · | Environmental Literacy | Science Communication | Applying Science |The Biscayne Bay Marine Health Inaugural Summit was held at the Florida International University Biscayne Bay campus. I flew down at the invitation of Jim Fourqurean, my long time friend and seagrass colleague, who provided a very nice introduction. There were around two hundred people in attendance and my role was to provide a lunch time talk to relate some lessons from other locations that were relevant to Biscayne Bay. I chose to focus on lessons from Moreton Bay, Australia and Chesapeake Bay and to not use slides, but rather talk. I have provided the text of my speech in this blog.

Biscayne Bay is a shallow barrier island lagoon, some 35 miles long. It contains many islands and historically-supported seagrasses, sea turtles and manatees. It is experiencing some very serious environmental degradation, with 2.7 million people in the small but crowded watershed. I was surprised to learn that many homes, even ones close to the Bay, use septic systems. I also learned that the sheet flow of water over the Everglades used to pass through the Biscayne Bay watershed. Seagrass loss, algal blooms and increasing turbidity are being observed in the bay. However, the bay does have a very solid monitoring program, including 83 water quality monitoring stations and seagrass monitoring for the entire Bay.

The conference organizers were Luiz Rodriguez, Steve Sauls, Irela Bague, Albert Gomez and Dave Doebler, who did an amazing job of putting together a full program. I ran into former UMCES colleagues Joe Serafy and Eric Buck, as well as Larry Brand who I knew from Woods Hole and when he visited in Australia on a phytoplankton collecting expedition.

One of the things that I appreciated about the people attending the conference was the passion they had for Biscayne Bay. They presented the newly coined “Harvey Award” to Miami-Dade Commissioner Daniella Levine Cava. The name of the award was in honor of Harvey Ruvin, Clerk of Courts for Miami-Dade County who is one of the staunchest supporters of Biscayne Bay. The award, created by Keith Clougherty, was a very attractive ‘sculpture’ using plastic refuse as construction material.

I appreciated that the conference, held in the building where the Florida International University students learn about hospitality, was a “Truly sustainable and zero waste event.” The food and drinks were superb.

Dave Doebler called himself just a “Dude in a kayak,” but he had initiated some impressive plastic marine litter clean ups. Jamie Monty from Miami-Dade County spoke about the monitoring and restoration initiatives supported by the county. Captain Dan Kipnis provided some impressive photographs and underwater video and spoke about his passion for the Bay. Charles Grisafi from NOAA told us about the marine debris program. Rene Price led a panel that included Tiffany Troxler, Jim Fourqurean, Patrick Shearer and Charles Grisafi. Tiffany emphasized the issue of sea level rise adaptation, and Patrick emphasized stormwater runoff issues. Jim addressed the issue of phosphorus overenrichment in the phosphorus-limited carbonate system. He also brought up the issue of contaminants like endrocrine disrupters and heavy metals. In the afternoon, we heard impressive local initiatives from Margarita Wells, City of Miami, Dara Schoenwald, VolunteerCleanup.org, Matt Anderson, City of Coral Gables and Walter Meyer, Parsons The New School. We also had breakout sessions to discuss priorities for government policies, infrastructure and public works, education and outreach, and research needs. I was in the research needs session, which Joel Trexler from FIU facilitated. Jim Murley from Miami-Dade County provided closing remarks with a historical perspective.

My lunchtime remarks were as follows:

Lessons from Moreton and Chesapeake Bays for Biscayne Bay

28 June 2017

William C. Dennison

It is great to be with you here. Thanks to my colleague and friend Jim Fourqurean for arranging the invitation. Forty years and a couple of months ago I came Miami to board a tall ship (R/V Westward on Sea Semester) at Dodge Island near where we are now and sailed out into the Sargasso Sea, up through Chesapeake Bay where I work now and end up in Woods Hole on Cape Cod where I ended up doing my PhD. Years later, I came back to board various University of Miami research vessels (R/V Calanus and R/V Columbus Iselin) to head to the Bahamas with this cute little graduate student (who is now my wife). So this place was the beginning of important things in my life.

I am going to tell you two stories; one about Moreton Bay in Australia and one about Chesapeake Bay, and draw 12 lessons relevant to Biscayne Bay from these stories. And then I will make 3 observations about Biscayne bay as an interested observer.

Twenty five years ago I headed off to Brisbane, Australia to take a job at the University of Queensland. The real attraction for me was the proximity to the Great Barrier Reef off the Queensland coast, kind of like coming to South Florida for the Florida Keys reef tract. I soon found myself splashing around in the bay adjacent to Brisbane, a city of 2 million people. This shallow subtropical embayment is called Moreton Bay and it supports abundant seagrasses, sea turtles and dugongs (the Australian version of manatees). Moreton Bay is not unlike Biscayne Bay and I even had a graduate student who did a comparison study of nitrogen cycling in Moreton Bay vs. Biscayne Bay. My graduate students and I began to realize how special Moreton Bay was, but also appreciated its vulnerability. Like South Florida, Queensland was a popular destination for vacationing Australians and the resident population began to swell. In fact, during the ten years that I was living in Queensland, it was the fourth fastest growing region in the world. So with this crush of a growing population, there were signs that Moreton Bay was suffering just like Biscayne Bay. Seagrass beds began to disappear, algal blooms were causing fisherman’s skin to peel off, and the water was becoming increasingly cloudy. Sound familiar?

Fortunately, the local elected officials turned their concern into action. They pooled their resources and funded the design of an integrated monitoring and research effort. We coined this effort the Healthy Waterways Campaign. Our tag line was “Because we are all in the same boat”. One of the first things we did was to create a newsletter, using color graphics with maps, photographs, diagrams and graphs. We printed 30 copies, since we had 15 people in our technical group and thought a few extra copies would be good to have. After a week, all 15 people requested additional copies, so we printed a hundred copies. After another week, we were out of copies, so we printed 300, figuring that we would have a lifetime supply. After two more weeks, we printed a thousand copies, and that became our minimum print run going forward.

LESSON 1: There is a public appetite for synthesized information, presented clearly and attractively.

So our next step was to produce a short, colorful book which we called the Crew Members Guide to Healthy Waterways, which was an invitation to join the crew. I was interviewed and asked to provide a ranking for the different regions of Moreton Bay. We called this the report card of the Bay, and the truth of the matter was it was generated by gathering half a dozen of my graduate students around a map of the Bay and we said, well the Bremer River upstream from the Brisbane River was the worst, let’s give that an F and the Brisbane River gets a D and the Eastern Banks with the seagrass and dugongs was the best, let’s give that an A. And then everything else was ranked in between. We just made up the grades.

In the meantime, our Brisbane Lord Mayor, Jim Soorley, had launched a week long Riverfestival to celebrate the Brisbane River that ran through the center of the city, not unlike the Miami River. As part of the celebrations, which included boat races, open air concerts, amazing fireworks, he asked us to gather world experts to share their stories just like you are doing today. This led to the creation of the International Riversymposium. The Lord Mayor went to Martin Albrecht, the CEO of Theiss, a global construction company located in Brisbane. Jim Soorley pitched the idea of having a Noble prize for river management, funded by Theiss. Thus was born the Theiss International Riverprize. The first recipient was the River Mersey in northwest England. The River Mersey flows through Manchester and Liverpool, cities that launched the Industrial Revolution. This river was so polluted that the city of Liverpool literally could not give away riverfront property, even with tax incentives and a million pound incentive. But decades into the restoration, they had salmon returning, they ran swimming competitions in the river and had turned the Liverpool property that no one would take into a four star hotel. The civic pride that the folks from Mersey had about their river was palpable.

LESSON 2: Environmental restoration can be a source of civic pride.

Because of the amazing story of the River Mersey, we were hoping for some good local media coverage, but the headlines of the Brisbane Courier Mail led with “Brisbane River rates a D”, and the TV stations showed footage of sand and gravel dredging in the river and reproduced the grades that we frankly made up one afternoon. And the story of the River Mersey ran on page 17, next to the local crime blotter. This was a wake up call for us in many ways.

LESSON 3. Local news outranked stories from far away.

Just as was said about politics “All politics is local”, the news is also best when it is local. People care about what they can see themselves and what affects them. We learned to tailor our messages around the watershed to the most location specific as was possible.

LESSON 4. Report cards need to be backed with data.

As scientists, we really couldn't go around making up grades. So we created a monitoring program that we called the Ecosystem Health Monitoring Program. This program is still collecting data and producing annual report cards.

We had just launched our Healthy Waterways program and were hoping for some rapid progress. To hear from the Mersey folks that they were decades into the restoration and were anticipating decades more to go made us take pause.

LESSON 5. Ecosystem restoration takes time.

If you consider that we have generally degraded things over many decades to centuries, you really cannot expect to turn things around instantaneously. Part of what we starting saying publicly was that it was going to take a long time. This is just as relevant for Biscayne Bay as anywhere else.

Back to our little Crew Members Guide book. Our program got the attention of the federal government who had funded the local councils and the Minister for Forestry and Conservation asked for a briefing. I got up and made my ten minute pitch and handed him the Crew Guide and sat down. He started leafing through the book as the next five speakers had their ten minute pitches, and he pretty much ignored them. The speakers were getting aggravated and kept saying, “Minister you can see from this slide that such and such . . .”, but he barely glanced up. At the end of all the presentations, he only had one question. “Where is my logo?”, he asked, pointing to the book. I answered, “Well, Minister, we wanted to be inclusive, because the six local councils that started this Healthy Waterways initiative are expanding to 19 councils and we did want anyone to fell left out, so we created this logo and tagline to be inclusive.” He said “Where is my logo?” again. So we ended up, at great expense, putting stickers on the back of the book to include his logo.

LESSON 6. It is important to share the credit, particularly with elected officials.

The local mayors also started to anticipate the report card and would call me up two weeks before the release and ask “How did I do?” And then “How did the mayor next door do?” They always wanted to see how they ranked relative to other jurisdictions.

LESSON 7. Peer pressure is a powerful human motivator.

And some of them would even ask if there was anything they could do for extra credit to improve the grades. Anyway, we went on to produce several books about Moreton Bay and Brisbane River, using the color graphics and synthesized information and provided everyone with the information about what was wrong with the Bay and where the problems came from. We were able to show using stable isotope tracers the extent of the sewage plumes from different sewage treatment plants, which catalyzed sewage treatment upgrades throughout the region. The sewage upgrades started to shrink the sewage plumes and this incentivized further studies and further improvements. We were able to show where the sediment runoff came from in the watershed and even identify that the cattle grazing in the stream was accelerating streambank erosion so fencing the cattle became the priority.

LESSON 8. Celebrate the small victories and build on success.

After ten years of doing this, I had the opportunity to try this Healthy Waterways experiment out on a bigger scale in Chesapeake Bay. Chesapeake Bay was ten times larger than Moreton Bay, had ten times the watershed size and ten times the population. So I waltzed into Chesapeake Bay, and said “Let’s do a report card—we have lots of monitoring data, it should be easy.” Well, that went over like a lead balloon. They said, “We have this fantastic model for the Bay that was better than monitoring data, and there was already enough information about Chesapeake Bay out there, in fact the Bay had its own monthly newspaper. We don’t need your color graphics newsletter either. Why are you even here?” This was disheartening, and after some particularly no good horrible days, I even considered packing up my family and heading back to Australia. But then the local newspaper, the Washington Post, published an expose’ on the over-reliance on the modeling—front page above the fold, and things began to change.

LESSON 9. Don't underestimate the power of getting the message out.

Since the U.S. Congress reads the Washington Post, they launched a Government Accountability Office investigation, sent the Office of Management and Budget to audit the Chesapeake Bay Program and the recommendations featured the need for independent rigorous verification of the restoration progress. Suddenly, this report card idea was not so far fetched. Eleven years ago, we produced our first Chesapeake Bay report card. The biggest surprise was not that the area around Baltimore was degraded—it is an old city right on the Bay—but that some of the rural areas on the eastern shore were just as degraded. This highlighted the need to understand what was happening and it became apparent that even though the human population is low on the Eastern Shore, the chicken population is huge—almost 600 million chickens produced every year. So the fertilizer used to grow the chicken feed (corn and soy) and the chicken manure from 600 million birds was causing water quality degradation. When the Eastern Shore counties found out that they were in almost as bad a shape as Baltimore, they were shocked into action. Back to LESSON 7, as peer pressure is indeed a powerful motivator. Baltimore did not want to continue to be the worst, so local business leaders have banded together and created the Waterfront Partnership. They bring Baltimore City and Baltimore County into their meetings and they ask how can we accelerate the clean up of the harbor? They have robots that crawl up stormwater drains to sniff out ammonia which detects illegal or leaky sewage seepages into the stormwater system. They bought boats to pick up floating trash, and even made giant water wheels that automatically scoop up trash that comes in from the major buried streams. They asked how they can reduce the waste streaming entering the stormwater system and the city officials said “We can’t afford more street sweeper trucks” so the businesses bought more street sweepers, and the city supplies the manpower to run the equipment. They also bought more trash cans, so people aren't as tempted to litter. They planted more urban trees. There is a long term ecological research site in Baltimore (like the one in Florida Bay) and the scientists found that an increase in 10% urban tree canopy is correlated to a 12% decrease in theft, robbery, burglary and shooting. In fact, they are actively digging up asphalt playgrounds and planting grass to decrease impervious surfaces and reduce flashy runoff carrying ‘urban slobber’ into the waterways. An interesting aspect of this is that if you observe kids playing on hard urban surfaces, the stronger kids become dominant, but if you observe kids playing in nature, the smarter kids become dominant.

LESSON 10. There are co-benefits to improving ecosystem health.

We had a Republican governor Bob Ehrlich in Maryland who instituted a “Flush Fee” (being a Republican, he avoided the word tax) which was used to fund sewage treatment upgrades. Upgrading large urban sewage treatment resulted in some dramatic rapid improvements. We then had a democratic governor, Martin O’Malley who created a Trust Fund for septic system upgrades and agricultural incentives, in particular cover crops. This funding has been used to reverse some of the degradation of agricultural areas. The current Maryland governor, Larry Hogan, is fully funding both programs instigated by his predecessors and is actively pursuing Chesapeake Bay restoration, serving currently as chair of the multi-state Chesapeake Bay Program executive committee.

LESSON 11. Ecosystem restoration can and should be bi-partisan.

The Chesapeake Bay restoration effort started in earnest in 1983, but it was entirely voluntary until 2010 when the EPA created the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) which is a mandatory nutrient diet. The other important thing that happened was instead of lofty, but distant, clean up goals that extended beyond the political life of elected officials, two year milestones were created to closely monitor the progress. This nutrient diet, with its tracking system, is starting to show real benefits. In addition to the federal and state monitoring programs, we are increasingly recruiting citizen scientists to aid in the monitoring efforts.

LESSON 12. Both carrots and sticks are important, but you need public accountability.

This year’s report card in which the Bay is subdivided into 15 reporting regions, shows that 7/15 regions are significantly improving. This is great news. Now in our eleventh year of releasing the Chesapeake bay report card our media reach was over 150 million people—that is half the population of the US. We still have a long way to go, and we are not declaring “Mission Accomplished”, but we are finally on the right track.

How do the Moreton Bay and Chesapeake Bay stories relate to Biscayne Bay?

First, in spite of population pressures, it is possible to reverse the negative trajectories, even though it will take time and sustained effort. From all accounts, Biscayne Bay is suffering and is heading in the wrong direction, but this can and should be reversed. Biscayne Bay would benefit from publicly released report cards to track progress.

Second, The world is looking for leadership. There are many tropical coastal megacities cropping up in the world, and Miami and Biscayne Bay can become a global model for sustainability. Biscayne Bay has been the forgotten Bay of Florida, adjacent to so many nearby icons like the world famous Miami beaches, the globally famous Everglades, Florida Keys and Florida Bay. It is time to allow the world to discover Biscayne Bay.

Third. The most important thing to do is what you are starting here today. Gathering elected officials, NGOs, scientists, elected officials, activists, and others to publicly declare “We care about the health of Biscayne Bay, which means we care about the city and the community as well”. This passion, coupled with growing community knowledge, can motivate positive environmental change.

Coming to Biscayne Bay was the beginning of some great things in my life, and I sincerely hope that this day, 28 June 2017, will be remembered as the beginning of something lasting, something positive and something pretty great for all of you. Good luck on your journey.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.