Combining visuals with narrative for effective science communication

Bill Dennison · | Science Communication |My collaboration with Randy Olson, the master of developing good narrative structure for communicating science, has led me to consider the parallels between developing effective visual graphics and good narrative.

Both narrative structure and visual processing are hard wired into the human brain. Brain scans of people watching a story unfold on videos show their brains are highly activated and they display the same activation as a group, compared to people watching videos devoid of a story (e.g., people walking through a public place). Brain scans of people viewing different color hues show a higher activation in some colors (e.g., red) than other colors (e.g., green). These observations show that our neurobiology makes us particularly attuned to stories and visual cues like color.

![Neural basis for narratives (left) and distinct hues (right). Credit: Hasson in Olson 2015 (left) and Neural basis for unique hues, Stoughton and Conway 2008 [pdf] (right) Neural basis for narratives (left) and distinct hues (right)](/site/assets/files/2524/brainhue-01-500x226.png)

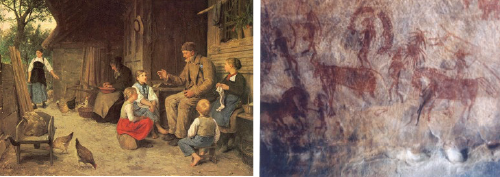

The earliest form of narrative according to Randy Olson is the epic poem of Gilgamesh, dating back to 4,000 B.C. I have made the case that an early form of visual communication is the development of stained glass by Egyptians and Romans and used extensively during the Medieval Period. The technique of combining metal oxides with sand to make glass created an opportunity to produce different colored glass that could be arranged using lead frames to create diagrams. These early forms of narrative and visual communication began to converge in the hand-illustrated books laboriously reproduced by Medieval monks. Printing presses were developed to allow more rapid reproduction of narrative and visuals.

Another reason that combining narrative and visuals is so ingrained in many people is through their first exposure to books through children's books. Every night in millions of beds, parents are reading richly illustrated children's books to their children. When I read my children some of my favorite Dr. Seuss books, I could recall my mother reading the same book to me. Reading books to my children was a wonderful way to reconnect with my parents. The stories and drawings were amazingly familiar decades after I had last read them. You cannot imagine a children's book with colorful drawings accompanying an interesting story.

Film and television combines narrative and visuals in a powerful way. Movies are often more entertaining than simply reading words or viewing still photos. For example, the prospect of reading a tome is much more daunting than watching the movie version. As much as I love to read a good book, the abundance of good film and television is fairly compelling to watch.

Combining narrative and visuals is important for three reasons. 1) Narrative and visuals engage the audience. Stories are more interesting than a string of facts and good visuals are compelling to view. 2) Narrative and visuals are memorable. It is easier to remember a good story than disassociated vignettes and good visuals are easy to recall. 3) Narrative and visuals shorten reading time. Readers/viewers can follow a storyline more readily and visuals can be quickly scanned.

Both narrative and visuals are not typically a big part of current science training or practice. Scientists are not taught how to form a narrative in their papers or presentations. Rather the focus is on data analysis and interpretation in context with the appropriate references. Figures are often an afterthought and are exported directly from data analysis tools like spreadsheets and statistical programs, complete with 'chart-junk' and often illegible fonts. Oral presentations relying on dot points and cluttered or illegible graphics are more typical than a compelling story illustrated with good graphics.

Randy Olson advocates for a 'narrative culture' using story circles to help one another hone our science stories. I advocate for a 'visual culture' using graphics circles to help one another to hone our science visualizations. We need to begin to form a combined 'narrative and visual culture' to integrate these approaches to form powerful science communication products.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.