Developing a report card for the Florida Reef Tract

Heath Kelsey · | Environmental Report Cards |Jane Thomas, Caroline Donovan, and I visited Ft. Lauderdale, FL to facilitate a workshop for the development of the Pilot Report Card for the Florida Reef Tract with our partners from NOAA's Coral Reef Conservation Program. The workshop and report card was a follow-up to the workshop for creation of the pilot report card for American Samoa. Together these report cards are designed to serve as a model for the rest of the regions where NOAA has responsibility for monitoring the condition of coral reef ecosystems.

We facilitated the process by leading the group through as much of our 5-step report card process as we could, given the time constraints of a two-day meeting. As usual, we made good progress on the first two steps, decided on approaches for designating benchmark conditions in step 3, and on designing the report card in step 5. The discussions were excellent, and as happens everywhere we go, we learned a great deal about the ecosystems we discussed.

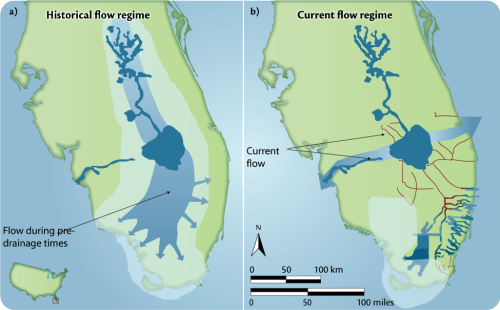

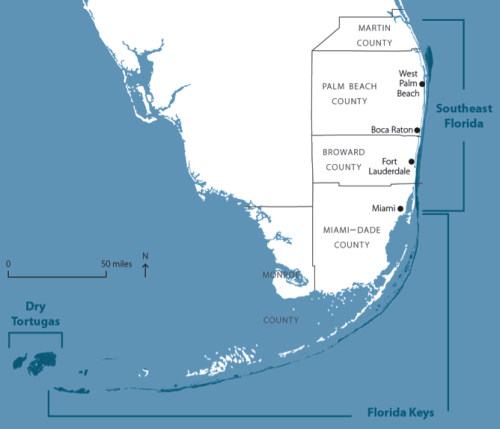

The Florida Reef Tract is the 3rd longest barrier reef system in the world, behind the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and the Belize Barrier Reef in Central America. The pressures on this system have been building since the early 1900s, when the Florida Everglades began to be drained through a series of canals, channels, and levees. From 1900 to 1940, the population of South Florida increased steadily, but not rapidly. Following the end of World War II, the population began to expand much more rapidly. Today, the population of the five counties in South Florida (Martin, Palm Beach, Broward, Miami–Dade, and Monroe) is 6.1 million people, a population greater than 33 of the states in the USA. Along with this population explosion and the severely altered hydrology in the Everglades, increases in tourism, commercial and recreational fishing, and most importantly, ocean temperatures and acidification have also occurred.

Participants in the workshop separate the reef tract into sections based on different criteria, but generally agree on three large regions along the coast: 1) Southeast Florida: from Martin County to Government Cut in Biscayne Bay, 2) the Florida Keys, from Government Cut to the Marquesas, and 3) the Dry Tortugas. Condition of the coral reef ecosystems in the Florida Reef Tract has declined from historic conditions. In the region including Broward and Miami–Dade Counties, coral cover has declined dramatically from pre-1970 conditions to the current time. Conditions north of Broward County and in the Marquesas are less well known—large-scale monitoring in these areas began in 2012 as part of NOAA’s National Coral Reef Monitoring Program. Generally, conditions are thought to improve on a gradient from Biscayne Bay to the Tortugas, as human population impacts become less acute, with the possible exception of the high population density immediately surrounding Key West.

The report cards are intended to communicate the condition of the coral reef ecosystems in each region individually and eventually, when all are complete, of all of the coral reef ecosystems under U.S. jurisdiction globally. The report card nominally follows the format of the priority indicators identified in the monitoring plan, with three main areas of focus: Biologic (including benthic and fish communities); Climate; and Social. Each of these thematic areas has indicators described to measure its condition, such as coral cover and ocean acidification.

Our approach to developing the two report cards was to allow teams from each region to develop a set of draft indicators that would be appropriate for their ecosystems. The indicators would be reconciled after drafting the first two, keeping in mind that the indicators should be similar to facilitate aggregation of results, and to design a set of indicators that can be used across the remaining regions of NOAA's Coral Reef Monitoring Program (NCRMP).

In practice, the indicators from each region were slightly different, and we will need to reconcile these indicators, which we intend to do through a series of web-based meetings to achieve consensus on the indicators, benchmarks to compare to, and analysis methods. The Ft Lauderdale workshop was a big step toward producing the pilot report cards for the American Samoa and Florida Reef Tract regions of the NCRMP, but of course more work needs to be done to develop a common framework for evaluating reef ecosystems.

About the author

Heath Kelsey

Heath Kelsey has been with IAN since 2009, as a Science Integrator, Program Manager, and as Director since 2019. His work focuses on helping communities become more engaged in socio-environmental decision making. He has over 15-years of experience in stakeholder engagement, environmental and public health assessment, indicator development, and science communication. He has led numerous ecosystem health and socio-environmental health report card projects globally, in Australia, India, the South Pacific, Africa, and throughout the US. Dr. Kelsey received his MSPH (2000) and PhD (2006) from The University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. He is a graduate of St Mary’s College of Maryland (1988), and was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea from 1995-1998.