Farming and Chesapeake Bay: Initiating a dialog with the Vansville Farmers Club

Bill Dennison · | Science Communication |The Vansville Farmers Club was formed in 1884 as a successor to the Maryland Agricultural Society at the home of James D. Cassard. Club members meet at each other's farms on a monthly basis, tour the facilities and share practices with each other. The Vansville Farmers Club created the first Farmers' Institute that developed into a statewide Farmers' Institute, which then evolved into the Extension Service of the University of Maryland. They also created the Vansville Farmers Club Scholarship Fund in 2006 for agricultural students in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Maryland.

On 17 November 2012, I spoke with the Vansville Farmers Club at the Annapolis Yacht Club, as a guest of Francis “Skip” Gardner. I provided three stories about Chesapeake Bay, drew three lessons from those stories, provided three handouts regarding Chesapeake Bay issues, and asked three questions of the Vansville Farmers Club. The first story regarded my experiences sailing into Chesapeake Bay in 1977 aboard a tall ship and meeting watermen of Smith Island, cadets at the U.S. Naval Academy and sailors at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. The second story began ten years later, when I lived aboard a boat moored in the Choptank River and transited the Bay from top to bottom. I talked of swimming on the extensive oyster reefs and seagrass meadows, learning about the 132 recipes for crab cakes from watermen, and watching skipjacks ply the oyster reefs of the Choptank River. And the final story was returning to Chesapeake Bay after living for ten years in Australia to find recurrent mahogany tides, oysters practically gone, blue crab numbers down and seagrasses declining. These stories have been described in a previous blog post.

The three lessons that can be drawn from observing Chesapeake Bay over this 35 year span of time are 1) shifting baselines of perception, 2) the evolving scientific needs, and 3) the importance of training the next generation of problem solvers. 1) The shifting baselines are a reflection of changes in what constitutes 'normal' in the mind of residents. Incremental change can be difficult to detect, and it can become 'normal' to have reduced fisheries, turbid water and annual algal blooms. Experiencing Chesapeake Bay over long time periods can allow for broader perspective that provides context for the current conditions. 2) The evolving science needs reflect both the level of knowledge about Chesapeake Bay, as well as the changing management challenges. The initial phase of estuarine science describing the Bay processes and organisms was followed by eutrophication science that identified the problems associated with excess nutrients. The development of Bay models and monitoring programs ensued and good tracking schemes (e.g., indicators, report cards) were developed. Current management needs are being addressed by scientists to develop better monitoring tools, better diagnostics of various environmental issues and better targeting of restoration efforts. Learning about the implications of climate change is also a major emerging scientific effort. 3) The importance of training the next generation of problem solvers by using Chesapeake Bay as a training ground is exemplified by the diversity of professions of my former shipmates. For example, my 1977 Westward colleagues have become social workers, doctors, scientists and business CEOs. Greg Marshall, my shipmate in 1987, invented the 'Crittercam' and works at National Geographic to apply unique underwater video imagery to answer compelling science questions. Ricky Arnold and I scuba dived in the Severn River to collect sediments for his thesis research, and Ricky applied his training in diving in his spacewalks as a Space Shuttle astronaut with NASA.

The three handouts that I provided the Vansville Farmers Club were A) the Chesapeake Bay report card, B) the Baltimore Harbor report card and C) the Measuring the Effectiveness of Best Management Practices newsletter. A) The Chesapeake Bay report card provided a sobering reminder of the challenges ahead for restoring Chesapeake Bay. But the positive trajectories observed in some of the report card reporting regions are testament for ecological tipping points and demonstrate the resilience of the Bay. B) The Baltimore Harbor report card is an example of a partnership between the business community, government, non-government organizations, academia, and citizens through the Healthy Harbor and the Waterfront Partnership Initiative. This provides an example of partnerships that I would like to emulate with the farming community. C) The Measuring Effectiveness newsletter provides an example of how government funding can be used to stimulate innovation and develop integrated restoration activities. The combination of the flush fee initiated by Governor Ehrlich for upgrading wastewater treatment and the Chesapeake and Atlantic Restoration Trust Fund initiated by Governor O'Malley, provide sustained funding streams that are being used to reduce Maryland's impact on Chesapeake Bay.

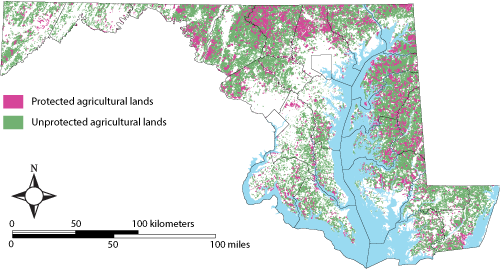

The three questions that I asked were the following: 1) Do you believe that climate change is real?, 2) How important is a healthy Chesapeake Bay?, and 3) What are ways that farmers can retain soil, fertilizers and pesticides on the fields where they are useful, instead of having them runoff into Chesapeake Bay where they are damaging? The answer to the climate question was an acceptance of climate change as a reality. The issue of whether or not climate change was human-induced was not universally accepted, but the approach of developing adaptation strategies to dealing with climate change was endorsed. The response to the question of valuing a healthy Chesapeake Bay was to emphasize the role that farmers would like to play in helping maintain a healthy Bay. The alternative of converting agricultural lands into housing developments was emphasized as a perverse outcome of creating regulatory or economic conditions that would force farmers to sell their land, with deleterious impacts on Chesapeake Bay. The third question of what farmers can do generated a response that the farmers were happy to be asked this question - they generally have not been consulted as to ways that they can contribute in this realm and are often portrayed as the Chesapeake villains. It was this third question that prompted a follow-up meeting in May 2013, which will be recounted in a separate blog entry.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.