Great Barrier Reef literacy

Bill Dennison · | Environmental Literacy | 1 commentsThe concept of environmental literacy derives from a series of programs that have established various literacy principles, for example, ocean literacy and Chesapeake Bay literacy. These distillations attempt to identify the essence of what an informed person needs to know. The literacy principles form the overall outline presented here, but it is in the richness of examples, stories and visual supporting materials that bring the literacy alive.

Seven environmental literacy principles for the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) are the following:

- The Great Barrier Reef is the largest coral reef complex in the world.

- The massive catchment of the Great Barrier Reef affects the reef.

- The Great Barrier Reef has regular, large scale disturbances.

- Climate change poses an immediate and real threat to the Great Barrier Reef.

- The Great Barrier Reef supports indigenous uses, shipping, recreational and commercial fishing and tourism.

- The Great Barrier Reef supports high biodiversity, including megafauna.

- The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is managed as a large contiguous unit.

1) The Great Barrier Reef is the largest coral reef complex in the world.

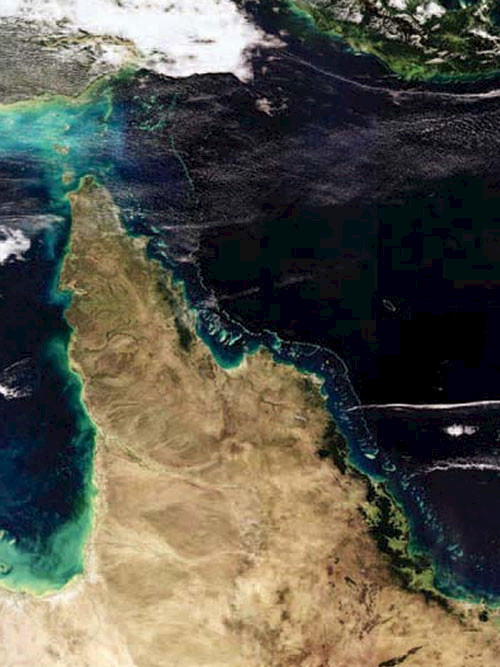

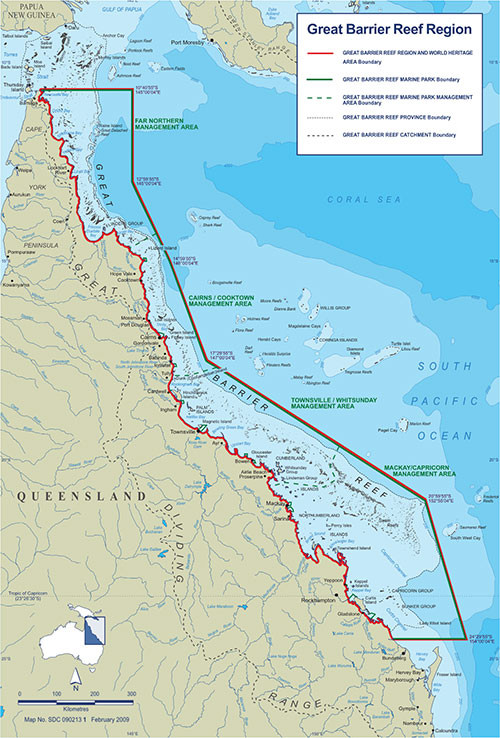

The Great Barrier Reef complex is comprised of over 2,900 coral reefs, and extensive seagrass meadows, mangrove forests, and inter-reefal hard and soft substrates. The reef extends over 2,600 km (1,600 miles) along the Queensland coast. The second longest reef complex in the world, the Mesoamerican reef (Yucatan, Mexico to Hondoras) only extends for ~1,000 km. The Great Barrier Reef is visible from space and is listed as a World Heritage Area. The total area is 344,400 km2 and contains 900 islands.

Due to its immense size, the Great Barrier Reef spans large gradients. Inshore to offshore gradients exist, particularly in regions where the reef is 200 km from shore. Scientists often divide the reefs into inner, mid-shelf and outer shelf reefs. A north to south gradient exists, stretching from 10°S at the tip of Cape York to 24.5°S at the southern limit in the Bunker-Capricorn group. A catchment runoff gradient exists, from the wet tropics which receives >2500 mm of precipitation per year, to dry conditions (<500 mm per year) with long intervals between rain events.

It is often difficult to describe the Great Barrier Reef--there are so many facets and different regions that it often leads to the adage about the blind men and the elephant. There are ribbon reefs, platform reefs, fringing reefs around continental islands, isolated reefs, reefs with and without coral cays, in short, many different types of reefs. Similarly, there are intertidal and deep water seagrasses, estuarine seagrasses, coastal seagrasses and seagrasses growing on reef platforms. There are estuarine mangroves, coral cay mangroves, coastal fringing mangroves, and continental island mangroves. We can describe a portion of the Great Barrier Reef very well, but a different region will have entirely different features.

2) The massive catchment of the Great Barrier Reef affects the reef.

The Great Barrier Reef catchment is 426,000 km2 in size, extending from the coast inland to the Great Dividing Range. This massive catchment affects the reef through runoff of freshwater, sediments, nutrients and toxicants. The Great Barrier Reef catchment is much larger in the southern portions, and contains two of the largest river basins in Australia, the Burdekin and Fitzroy River basins. A variety of land uses affect the runoff of water and quality of the water that runs into the coastal portion of the reef, known as the 'Great Barrier Reef lagoon'.

The principal land use in the Great Barrier Reef catchment is grazing (primarily cattle). Cattle disturb the soil, particularly near streambeds which promotes soil erosion. There are intense agricultural land uses, particularly sugarcane and horticulture (e.g., banana, pineapple), predominantly in the Wet Tropics, Mackay/Whitsundays and Burnett/Mary regions. There are large areas of forest and protected lands, particularly in the northern portions of the GBR catchment. Runoff of freshwater, sediments, nutrients and pesticides from the catchments affects the inshore portions of the reef.

map (from Reef Water Quality Protection Plan Secretariat (2009) Great

The rainfall patterns are different in different parts of the catchment. In the Wet Tropics, predictable summer rains occur every year and the river plumes enter the reef annually. In contrast, the large catchments in the southern portions of the reef (Burdekin and Fitzroy) often do not have enough rain to have river flow. The rivers from these catchments can go many years without flowing onto the reef. On the occasion that these rivers do flow, the plumes can be substantial. Flood plumes on the Great Barrier Reef generally head north, due to prevailing southeasterly breezes and the deflection of flows to the left in the southern hemisphere due to Coriolis forces.

Terrigenous sediments, nutrients and toxicants are deposited close to shore in a 'coastal wedge'. Winds and tides resuspend the fine grained sediments long after the flood event that delivered the sediments, thus there is a legacy effect of floods. Tropical ecosystems are particularly sensitive to nutrients from terrigenous sources. Eutrophication can be expressed as expansion of mangroves, seagrasses and soft corals, with a contraction of hard corals. Coral reproduction is particularly sensitive to eutrophication. Extreme eutrophication can lead to fleshy algal overgrowth of corals. In an experimental nutrient addition using 12 replicate patch reefs (Elevated Nutrients on COral Reef Experiment (ENCORE)), automated nutrient additions (control, +N, +P, +N+P) were conducted for 3 years. The initial low dosage nutrients was only detectable in coral reproduction, but higher dosages resulted in changes in various components of the coral reef ecosystem.

3) The Great Barrier Reef has regular, large scale disturbances.

Most of the Great Barrier Reef is within potential pathways of tropical cyclones, large low pressure systems that generate extreme winds and large waves. The outer reefs receive the highest energy waves, but the inshore reefs can be susceptible to wave damage also. Another natural disturbance is extremes in temperature, particularly warm water temperature which leads to coral bleaching. Bleaching refers to the white color that results from the expulsion of the symbiotic algae that live symbiotically within the cnidarian host. Other stressors can cause bleaching, including cold temperatures and freshwater. Massive outbreaks of Acanthaster planci (crown-of-thorns seastar) can lead to loss of coral cover. Cyclones, warm temperature extremes and outbreaks of crown-of-thorns are natural disturbances which have occurred historically. The frequency and intensity of these events appears to be increasing, and anthropogenic causes have been implicated.

4) Climate change poses an immediate and real threat to the Great Barrier Reef.

There are many facets of climate change that will affect the ecosystems of the Great Barrier Reef. Increased bleaching frequency due to high temperature events compromises reef health. Bleaching maps reveal bleaching in both inshore as well as offshore reefs. Increased sea surface temperature for the Coral Sea is one of the observed and forecasted climate change trends.

Ocean acidification is another climate change impact on the Great Barrier Reef. The amount of dissolved carbon dioxide in seawater is affected by atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Recent research on calcification rates in corals indicates a possible slowing of calcification over the past decade. Increased monitoring of ocean acidification on the Great Barrier Reef has recently been initiated in response to this concern.

Enhanced rates of sea level rise are also a threat to reef survival, as net accretion of calcium carbonate will be necessary to avoid having the reef 'drown'. Seagrass meadows and mangrove forests are also susceptible to both sea level rise and high temperature events. Mangroves are particularly sensitive to relative sea level rise.

The issue of increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, with associated runoff plumes, is a concern, based on climate projection scenarios.

5) The Great Barrier Reef supports indigenous uses, shipping, recreational and commercial fishing and tourism.

The Great Barrier Reef has been used by indigenous Australians since it was formed over the past ten thousand years. Aboriginal Australians have used mangrove forests for various building materials and a place to forage for food, and have used seagrass meadows and coral reefs to forage for food. More recently, the Great Barrier Reef has become a major tourism destination for many visitors from the all over the world. The amount of money generated by Great Barrier Reef tourism has been estimated (in 2010) as $5.6 billion dollars annually. This is due to day trips, live aboard boats, and island and beach resorts and all of the associated travel, hotels, and restaurants that accompany this tourism. Large, fast catamaran boats take tourists out to the outermost reefs on day trips. The fishing industry is both recreational and commercial, with different portions of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park being zoned for different uses, some of which allow various fishing activities. There is bottom trawling for shrimp, scallops and bottom fish between reefs, and line fishing for fish on and around reefs, net and pot fishing between reefs.

6) The Great Barrier Reef supports high biodiversity, including megafauna.

The Great Barrier Reef supports a high biodiversity of corals, seagrasses, mangroves, and associated invertebrates and vertebrates. The vast areas of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park support not only coral reefs, but also seagrass meadows and mangrove forests. As a result, there are large populations of dugong which feed on seagrasses, sea turtles which nest on coral cays and feed throughout the reef, sharks that reside both offshore and inshore. One of the unique features of the reef biodiversity is the prevalence of large megafauna. Animals like whales, sharks, rays, dugong, sea turtles, crocodiles, and grouper are common in Great Barrier Reef waters. The prevalence of megafauna affects the ecology of the reef complex. For example, sharks are top predators in pelagic ecosystems and dugong grazing structures seagrass communities. There is a trend of increasing biodiversity moving northward into more tropical conditions.

Increasingly, the Great Barrier Reef is becoming the last place on earth where there are large tracts of intact coastal tropical ecosystems with megafauna that maintain these ecosystems in a largely natural state. Many other regions of the world, like the Caribbean and the islands of the Indo-West Pacific, have significantly reduced numbers of megafauna and severely degraded tropical ecosystems. As coral reef degradation occurs globally, the Great Barrier Reef will become more and more unique, particularly regarding megafauna.

7) The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is managed as a large contiguous unit.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority is a federal authority and the state of Queensland is also involved in the management of the reef. The Great Barrier Reef has been declared a World Heritage Area. There are also various non-government agency activities in the Great Barrier Reef. There is complex zoning on the reef, with different suites of activities permitted in different areas, including some areas exclusively designated for science.

General References

Furnas, M (2003) Catchments and Corals: Runoff to the Great Barrier Reef. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Australia.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2009) Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2009. Townsville, Australia.

Hutchings, P, Kingsford, M, Hoegh-Guldberg, O (2008) The Great Barrier Reef: Biology, Environment and Management. CSIRO Publishing. Collingwood, Australia.

Johnson, JE, Marshall, PA (eds) (2007) Climate Change and the Great Barrier Reef. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Australian Greenhouse Office, Australia.

Koop K, Booth D, Broadbent A, Brodie J, Bucher D, Capone D, Coll J, Dennison WC, Erdmann M, Harrison P, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Hutchings P, Jones GB, Larkum AWD, O'Neil JM, Steven A, Tentori E, Ward S, Williamson J, Yellowlees D (2001) ENCORE: The effect of nutrient enrichment on coral reefs. Synthesis of results and conclusions. Marine Pollution Bulletin 42(2):91–120

Reef Water Quality Protection Plan Secretariat (2009) Great Barrier Reef Technical Report Card -- 2009 Baseline. IAN Press, USA.

Reid, C, Marshall, J, Logan, D, Kliene, D (2009) Coral Reefs and Climate Change: The Guide for Education and Awareness. The University of Queensland, Australia.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Next Post > Global use of IAN symbol libraries

Comments

-

sabri 11 years ago

first of all i would like to thank to Dr Bill Dennison who share this valuable article, for me who staying in Bali Island this article really help me out to know more about reef, again thank you Dr Bill Dennison