Integrating science with people: Creating the corpus callosum connections

Bill Dennison · | Environmental Literacy | Science Communication |As part of the Integrated Water Management Master's program offered by the International WaterCentre (IWC), a four person panel was convened which included Poh-Ling Tan, a lawyer from Griffith University, Helen Thompson, an anthropologist in the private sector, Dr. Stephen Mahler, an engineer from the University of Queensland, and I was the natural sciences representative. Bruce Missingham from the IWC was the moderator. The topic for the panel was about how we approach integration from our different disciplines. While Stephen and I emphasized how we used various tools to collect and synthesize quantitative data, Pauline and Helen talked about incorporating descriptive, qualitative considerations like the spirituality that different peoples associate with water and water issues. These different perspectives can lead to erroneous statements like "Social science is not a science", as described by Helen.

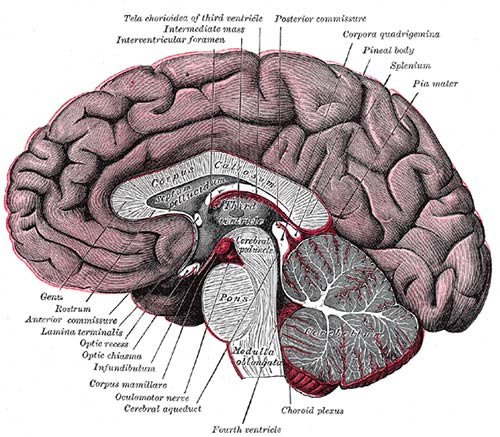

As our panel sat side by side in front of the students, it occurred to me that we were arranged as the lawyer and anthropologist on stage right and the engineer and scientist on stage left. We were presenting an analytical and rational left brain alongside an artistic and empathic right brain. So the analogy of a corpus callosum came to mind--the bundle of neurons that connect right and left hemispheres of the human brain. The corpus callosum is what we need to solve problems which can tap both hemispheres of the brain. It was apparent that the issues that we were discussing like the management of a tributary of the Brisbane River, Oxley Creek, or the management issues associated with extraction of coal seam gas require the best analytical tools, legal advice and sociological assessments that we can assemble. In order to integrate these different perspectives, the corpus callosum of connectivity is needed.

The perceptive students asked how to create the corpus callosum of connectivity. Some ideas that emerged from this question included interesting observations. One observation was the importance of assembling multi-disciplinary teams. The rules of engagement were discussed; 1) establish common goals or shared vision, 2) have a robust debate and agree on what was agreed and what was not--go forward with the agreed portions, 3) create opportunities to build relationships and trust. The differences between educational models were identified, with the Anglo compartmental model versus the more integrated Latin versions of science. In addition, the different push toward synthesis in some disciplines versus the push to generate diversity in others was identified.

The analogy of the corpus callosum was expounded by Dr. Brian McIntosh, who spoke of what happens when the corpus callosum is severed. Brian spoke of the 'alien hand syndrome' where the right brain which controls the left side of the body would develop a conflict with the left brain which controls the right side of the body, and the result could be one hand of a person would strike out randomly. This analogy of severing the corpus callosum can be made with severing considerations of science from the human elements while attempting environmental problem solving.

The topic of integrating science with traditional knowledge was raised and I recalled a favorite book of mine, "Words of the Lagoon: Fishing and Marine Lore of the Palau District of Micronesia" by Bob Johannes. Bob was a marine ecologist who spent enough time in the island nation of Palau to build relationships with the local fishermen. Over time, he recorded their extensive knowledge of fish movements, life cycles and interrelationships and where possible, compared their traditional knowledge with the scientific literature. What he found was that the scientific literature invariably confirmed what the local fishermen knew, but that the breadth and depth of traditional knowledge far exceeded scientific knowledge.

The engagement of government, industry, the community and academia in environmental issues was discussed. Educating various people during the project was identified as important, particularly in fast evolving fields where government struggles to stay informed of new developments. Learning to ask the right questions with the example as deriving the appropriate terms of reference for an issue was identified as a key element of any project. Developing a strategy of 'quick wins' in which positive outcomes are celebrated widely was recommended. In addition, the development of participatory monitoring programs (or 'citizen science') was discussed as a way to engage the expanding demographic of skilled and still active retired people. The role of academia to remain independent and to be able to advise government was discussed, with the ability of academics, if needed, to go directly to senior policy makers or to the public.

The panel discussion was wide ranging but remained focused on environmental problem solving and served as a model of interdisciplinary corpus callosum connectivity. With new relationships and a short time slot available, most of the panel agreed with each other, but a more in depth discussion would likely bring out some disagreements and this would be a good way to explore conflict resolution in the future. It was a stimulating discussion and much more engaging than the typical 'death by powerpoint' that occurs in many academic settings.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.