Learning About Transdisciplinary Science Through Graduate Teaching

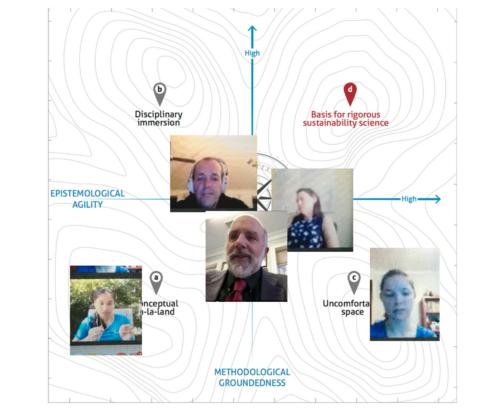

Bill Dennison ·Last semester, Heath Kelsey and I taught a Marine Estuarine and Environmental Science (MEES) course titled “Transdisciplinary Science For Environmental Problem Solving." Our three Integration and Application Network students, Suzi Spitzer, Vanessa Vargas and Natalie Peyronnin enrolled in the 2 credit course. Professor Michael “Dougo” Douglas from the University of Western Australia attended most classes, in spite of the fact that it was 10 pm - 12 am in Perth, Australia. We used BlueJeans software for our weekly classes. BlueJeans allowed me to participate in the course from some bizarre locations, including at a parking lot along the Connecticut turnpike, in the wee hours in a Darwin hotel, and at the National Academy of Science in Washington, DC during the Science of Science Communication III conference.

Dougo and I began our collaboration when he and his wife Samantha Setterfield spent part of his 2012 sabbatical from Charles Darwin University (his previous institutional affiliation) with us in Maryland. Dougo, Sam and I came up with some concepts about how to approach science applications from our collective experiences in Australia and the United States. We followed up the sabbatical with discussions at conferences we attended, including a discussion that followed a recent session that Dougo attended at the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) in Annapolis. We drafted a rudimentary manuscript, but it was this MEES course that really allowed the paper to come together, thanks in part to the perspective of the graduate students participating in the class.

One of the concepts that we developed during Dougo’s sabbatical was the “A team” vs “B team” researchers, originally suggested by Dougo and Sam with Stan Gregory at Oregon State University. The “A-team” researchers were well-published and highly cited, and the “B team” researchers spent considerable energies developing and maintaining relationships with stakeholders at the expense of publishing as many peer review scientific papers. We all decided that we were content with our self-appointed status as “B team” researchers, taking pride in the ecological outcomes that we achieved by working closely with a diversity of stakeholders. We felt the need to share our “B team” perspectives to other “B team” researchers, including the lessons that we learned about how the people, projects and pathways could be aligned to initiate timely actions.

Holding these ideas in our minds, Heath and I decided to teach a graduate course last fall in order to survey and update the relevant literature, analyze the word usage and literature citations, and integrate our experiences with the literature. This turned out to be a great decision. By the end of the course, we felt that we were able to gain a mastery of the transdisciplinary science literature. We read and discussed a lot of papers, some of which made us angry, and some of which were really insightful. This literature survey was greatly enhanced by Vanessa Vargas’s literature citation network analysis which allowed us to target the key papers in various aspects of transdisciplinary science. Analyzing the word usage allowed us to develop the historical context of the evolution of the transdisciplinary approach. And in the end, we feel more confident that our unique perspectives can make a valuable addition to the literature.

Dougo, Heath and I found the transdisciplinary science literature to be really informative. We both wished that we had discovered this literature earlier in our careers of applying science. One of the motivations for the paper we are writing is to draw attention to this transdisciplinary literature and provide guidance to our scientific colleagues interested in pursuing transdisciplinary science.

We titled both the course and the manuscript “Transdisciplinary science for environmental problem solving” to reflect the two different camps; researchers and stakeholders/practitioners. Researchers are comfortable using the term ‘transdisciplinary’ as a progression from disciplinary, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary. Stakeholders/practitioners are more concerned with solving environmental problems, and the term ‘transdisciplinary’ does not resonate with them. In straddling the worlds of academic science and the practitioners with their environmental challenges, we chose a title that conveyed both approaches: the theory and the practical application.

The advantages of formalizing our interactions through a course on transdisciplinary science were several-fold. The weekly schedule kept the topic current so we didn’t have catch up each time we got together. Also, the graduate students provided fresh perspectives that forced us to reanalyze our assumptions and to better articulate our ideas. Talking about the literature in-depth gave us a broader perspective of the different trains of thought from different fields. The continual development of figures and analyses allowed to better understand this field and stimulated us to provide fresh insights regarding the field. Finally, the drive to publish in a high quality journal exerted by the students redoubled our efforts to complete this manuscript.

Reference:

L. J. Haider, L.J., Hentati-Sundberg, J., Giusti, M., Goodness, J., Hamann, M., Masterson, V. A., Meacham, M., Merrie, A., Ospina, D., Schill, C., Sinare, H. (2017). The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sustainability Science. PDF available here.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.