Open-Concept Disciplines

Shannon Hood ·By: Shannon Hood

The readings for this week drew me to think a lot about home construction. As the daughter of an architect and builder, I grew up looking at building plans with my dad and walking around in framed homes. Years ago, it was standard to have many walls and doors in homes, with much delineation between the kitchen, dining room, living room, study, etc. Plenty of walls; a good sturdy home. As time has gone by, it's become more trendy to see open concept living spaces (see nearly every episode of Fixer Upper), with the kitchen, living, and dining spaces blending seamlessly into one another. They may look great, but they make the framer's job tricky! In the absence of many load-bearing walls, there has to be a great foundation and sturdy, strategically-placed beams to hold up all that weight.

You may be wondering why I'm talking about building design in reference to a course on Environment and Society. It's a fair question, I'll give you that one. This week's readings were about removing the boundaries placed upon academics by our disciplines. Initially, I found myself thinking - 'no way, we need our specific areas of discipline to provide the pillars on which our collective body of knowledge and progress can grow.' However, after our class discussion, I have a different perspective on the matter. Perhaps I was taking the readings too literally. We'll get back to that later, and see if you agree with my change of heart. First, I'll take you through the class discussion and we'll come back to home building 101.

We started out with some housekeeping issues (last home reference for a while, cross my heart). Our final project consists of working in small groups to develop proposals to integrate cultural and natural resources in U.S. National Parks within the National Capital Region. During next week's class period, our groups will meet in College Park and present our projects to our classmates, professors, and representatives from the National Park Service(!).

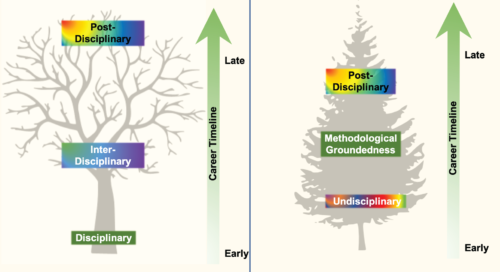

Our class's teaching assistant, Suzi Spitzer, began by sharing her academic background up to this point in her career. A few other students in the class shared similar stories; beginning in a given discipline but feeling called to an interdisciplinary approach over time. Others shared the opposite experience, having begun their academic careers in interdisciplinary work and refining their specific discipline in graduate school. This seems to be a newer approach to academia in sustainability sciences, unlike the tradition of becoming an "expert" in a single discipline, and then branching out later in their career.

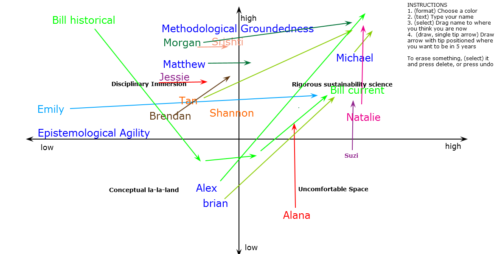

The experience of early-career researchers who engage in problem-based interdisciplinary research may be termed undisciplinary. The term refers to individuals learning from a broad range of approaches, rather than delving first into a specific discipline1. We spent some time examining the "Interdisciplinary Compass," and engaged in a class exercise where we identified our place on the compass (and learned a little bit about zoom's technological capabilities in the process!).

The compass is broken into four quadrants, separated by two axes. The horizontal axis represents epistemological agility, or one's ability to understand different ways of knowing things. Different realms have unique approaches to gaining knowledge which may be different from our own, but are valid nonetheless. The vertical axis represents methodological groundedness, or how well someone understands technical methodologies that can be used to conduct research. The class was asked to write our names where we think we currently exist on this compass, and draw an arrow to where we'd like to end up on the compass. Some of us found the technology easier to use than others. Despite Suzi's perfectly clear instructions, I was in the latter category and spent most of the time trying to find the right drop-down box; I never did manage to figure out how to draw an arrow. Kudos to my classmates who pulled it off so smoothly.

However, the point of the matter is, as students engaging in a largely interdisciplinary field, we tend to seek both high methodological groundedness and high epistemological agility in our future careers. While the majority of the class currently identifies in the "Disciplinary Immersion" quadrant, with a relatively higher understanding of methodologies than epistemology, at least a few of our classmates self-identified in each of the four quadrants. It was encouraging to hear from our professor, Dr. Bill Dennison, that he has found himself in different places within this compass throughout his career. It gives us a general frame of reference for how to think about topics we may need to understand more fully in order to reach a point where we understand both how to conduct our own research, as well as how to respect the knowledge contributed by others.

The concept of self-identity was discussed as a challenge to undisciplinary students. Lacking a clear-cut background in any one area has left some students feeling like "academic immigrants," as noted by Munar2. A few members of our class identified with this concept of feeling as though they lack a clear academic identity. While this lack of clarity or even downright confusion may be frustrating, it's not necessarily a bad thing.

Rather than strictly defining ourselves based on our disciplines and academic backgrounds, perhaps we, as academics, should start with the why. Why are we motivated to do what we do? What are we hoping to achieve? We are accustomed to introducing ourselves by our institutional affiliation, our job title, and our current projects. However, a more boundary-spanning approach would be to introduce ourselves based on what we're trying to achieve, and what motivates us to do the work.

This approach, of speaking more personally about how we relate to our work, may help to remove some of the unfortunate stigmas of scientists3 as elitist, esoteric men in white lab coats. That's not us (promise!); we're just people looking to solve problems. Perhaps communicating about ourselves in this more personal way will help to negate that stereotype.

A tool for applying such an accessible science approach, is citizen science. Well-designed citizen science projects, such as the Citizen Lake Monitoring Network in Wisconsin, can engage a diverse audience, collect a robust dataset, and result in a community which is well versed in scientific methods.

Back to our home analogy. After hearing an assessment of undisciplinary research in practice, I see that the approach does not advocate for tearing down all the metaphorical pillars which uphold our scientific rigor. Rather, it widens the foundation from the start, creating a strong foothold from which to build well-balanced pillars of knowledge. Further, it does not seek to replace other approaches to learning, but rather to broaden accessibility of the sciences in our quest for knowledge and understanding.

References

1. Haider, LJ; Hentati-Sundberg, J; Giusti, M; Goodness, J; Hamann, M; Masterson, VA; Meacham, M; Merrie, A; Ospina, D; Schill, C; Sinare, H. (2018, January). The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sustainability Science: Open Access. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11625-017-0445-1

2. Perneky, T; Munar, AM; Wheeller, B. (2016, July). Existential Postdisciplinarity: Personal journeys into tourism, art, freedom. Copenhagen Business School. https://research-api.cbs.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/55425630/ana_maria_munar_existential_postdisciplinatiry_publishersversion.pdf

3. Pandya, R. (2018, July 9). It's time to shake science's superiority complex. Thriving Earth Exchange Blog. https://thrivingearthexchange.org/its-time-to-shake-sciences-superiority-complex/

Next Post > Representing UMCES at the 12th International Conference on the Environmental Management of the Enclosed Coastal Seas

Comments

-

Morgan 5 years ago

Shannon. Wow. What a great blog. I loved the analogy, and you made the class discussion so relatable! I also really enjoyed your second image. I think in general, this topic is going to become more prominent in upcoming generations of researchers.

-

Alex Sahi 5 years ago

I like the self reflexive method of writing this blog. I think it came out great! I think it highlights a path to where undisciplinary work is, and where it is going. It also is a piece of undisciplinary writing in and of itself which is a very cool take on the blog assignment.

-

Emily Nastase 5 years ago

Shannon, this is great! I never would have thought to compare disciplines to building a house. You've got me wondering though, what the limits are to undisciplinary learning? Just as a house has structural limitations, can undisciplinary training only span a certain amount of topics/disciplines before it becomes unstable? I imagine with the undisciplinary approach it would be easy to fall into "conceptual la-la land" or "an uncomfortable space" on the Interdisciplinary Compass.

-

Natalie 5 years ago

I love your writing style - so conversational. Glad you took us on your journey of seeing the positives of working across boundaries.

-

Tan Zou 5 years ago

Hi Shannon. I really like your blog! I like how you compare the “open concept living spaces” with “removing the boundaries placed upon academics”. I think the way they are similar to each other indicates that the challenges we interdisciplinary or undisciplinary students are having right now are not new. We can always learn from other fields about how to deal with these challenges. We are not alone. I also like how you plot the topics we discussed in the class by yourself. They are effective ways to show the audience not attending our class what we discussed and understood.

-

Brendan Campbell 5 years ago

I think defining yourself based on motivations does help to negate the 'men in white lab coats' feeling. Lately I have noticed that I have been defining myself more generally based on what outcomes I am looking to achieve rather than as a scientist and I think others respond positively to that. I think doing this is more personal, like you said. We all have problems we want to solve we all just have different strategies for doing it and that is perfectly acceptable.

-

Matthew Wilfong 5 years ago

Wow, what a great analogy! I know I have succumb to watching far too many Fixer Upper episodes so the analogy hits the nail right on the head. I agree that finding an identify as a scientist attempting to be "undisciplinary" is incredibly tough and leave one susceptible to the ever-present "imposter syndrome". I do believe the future of science is undisciplinary, but unfortunately I think we will be stuck with the current scientific format for a bit longer or until the current graduate students "undisciplinary-trained" progeny become the principle investigators themselves.

-

Brian Scott 5 years ago

Every time I buy a house I immediately start tearing down walls. I finally had to stop buying houses.

So, I completely get where Shannon was going. No boundaries doesn't mean no boundaries, it's more about opening up - just like opening up living spaces. It's about changing the boundaries and getting rid of barriers. The boundaries are great - they keep things in place. But, to make changes, walls have to come down. -

Srishti Vishwakarma 5 years ago

A perfect example of architect and buildings to start off the article. Citizen science does help to broaden the approaches to learning. It breaks the boundaries and help communities learn from each other.