Peter Oliver's top ten books about science

Peter Oliver · | Science Communication | Applying Science | Learning Science | Field Manual for Water Quality Monitoring in Schools: An Environmental Education Program for Schools, Keith Mitchell & Bill Stapp

Field Manual for Water Quality Monitoring in Schools: An Environmental Education Program for Schools, Keith Mitchell & Bill Stapp

I found this to be a very useful book when I started showing kids how to monitor streams. There are some inspirational things in the book, particularly where they talk about all the different places in the world where this approach is being used.

Shouldn't Our Grandchildren Know? An Environmental Life Story, Graham Chittleborough

Shouldn't Our Grandchildren Know? An Environmental Life Story, Graham Chittleborough

Chittleborough was a scientist with CSIRO in Western Australia who wanted to show his grandchildren some of the things he thought were special, but found that many of them were gone. Chittleborough had the skills and the knowledge about the environment and he wrote this book to attempt to impart this knowledge to the next generations.

The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology, Theodore Roszak

The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology, Theodore Roszak

Roszak talks about the 'neon telephone' where there is someone from an Eastern block country and they go into a store in Hong Kong and it is full of neon telephones. This person leaves the shop crying and says "I don't understand, how many telephones can one person want or need?" He walks into the next shop with 25 brands of toothpaste and he was used to only seeing one brand in stores in the Eastern block country. He considers this variety a form of madness. Roszak points out that it is stupid to have so many choices, yet we like to have choices. For the environmental educator, the concept that having many choices may not be a good thing and there are certain best practices that we should be promoting. But the human desire for lots of choices becomes a bit counterintuitive, and this is something that we have to deal with.

The Power of Partnership: Seven Relationships that will Change Your Life, Rains Eisler

The Power of Partnership: Seven Relationships that will Change Your Life, Rains Eisler

Rains Eisler is an organizational consultant and I read her book because when I worked for the government, partnerships were the rage and everyone talked about partnerships (e.g., win-win situations). I could see that effective partnerships were not happening, so I read The Power of Partnerships. What Eisler talked about was a partnership culture and a dominated culture, and mainly we work in a dominated culture where power is used so that one group of people has dominance over another group of people. Partnership power is where power is really shared, where people are given power to really do something.

We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change, Myles Horton and Paulo Freire. Brenda Bell, John Gaventa and John Peters (eds)

We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change, Myles Horton and Paulo Freire. Brenda Bell, John Gaventa and John Peters (eds)

Horton and Freire are two of the biggest educational thinkers in the world. Freire was a Brazilian educator who raised the issue of pedagogy of the oppressed. Horton was an American educator who was famous for his role in the U.S. civil rights movement for African-Americans. The book is essentially two old blokes having a conversation like the one that stimulated Bill and me to write this book. The title, "We Make the Road by Walking", provides great symbolism. You don't have to know exactly where you are walking, but you have to know what you are doing.

Critical Social Science: Liberation and its Limits, Brian Fay

Critical Social Science: Liberation and its Limits, Brian Fay

When I use the terms, enlightenment, empowerment and emancipation, I am mostly thinking in terms of critical social science. There are different sorts of social science, there is some that is very positivist, treating people as objects. We observe people, and often don't let them know that they are being observed. We conduct experiments and analyze one parameter at a time like in laboratory experiments. Then there is interpretive social science, starting with anthropologists who not only observed people, but also asked them why they did what they did and learn from them. In a way, the scientists handed over the clipboard and asked people to be involved. There is a third social science, Brian Fay's critical social science, in which the clipboard is fully handed over to people who act as co-researchers and we will work on something that is important to the people being studied. The new knowledge generated forms enlightenment, the knowledge then informs and empowers people for social change. Critical social science fits very well with praxis (practical, thoughtful doing) and solving wicked problems.

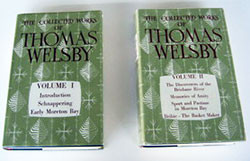

The Collected Works of Thomas Welsby: Volumes 1 and 2, A.K. Thompson

The Collected Works of Thomas Welsby: Volumes 1 and 2, A.K. Thompson

A beautiful story in this book is about two brothers who are very reliable witnesses reporting that they observed a herd of dugong about a mile and a half long and three hundred yards wide in between Moreton Island and Bribie Island. They said that at any one time there were a hundred dugong breaching to breathe. You tell this to young people today and they won't believe you. When a young scientist says that the Bay is in good condition, then I tell them that they need to read Welsby. Understanding the environmental history of a place is crucial.

The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Malcolm Gladwell

The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Malcolm Gladwell

I put Tipping Point on the list because it is about social change. When we do all this thinking (phronesis), we get to the point where we want to do something. We have a prudent understanding of what should be done, so let's go do a bit of doing (praxis). Malcolm Gladwell gives us some practical clues about what is needed; salesmen, mavens and networkers. If you produce 'sticky' ideas with the right numbers of people involved, you can have social epidemics that work for the good. An example is creating a social epidemic about articulating values clearly so that scientists know where to channel their efforts for future management of the Great Barrier Reef. Developing the power relationships where power is shared among stakeholders, like farmers in the catchments of the Great Barrier Reef, could develop 'sticky' ideas that could benefit the reef. Tipping Point affected me because it was practical.

Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism, J. Philip

Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism, J. Philip

When I started my Masters, my supervisor sent me on a task of finding the first occasion in Western thought. What I was reading this book for was attempting to find the origin of thinking that influenced me. I learned that what I consider to be true is not often examined. For example, we base our whole economic system on the assumption that resources are infinite. Yet, that is not using our 'Nous' (that which is known). This book helped crystallize my environmental philosophy.

Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development, Allen Irwin

Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development, Allen Irwin

There are a few different origins of what we call citizen science that sprung up around the world. Irwin provides a strong case for what comprises citizen science. He also believes that citizen science helps communicate the scientific approach to the surrounding area. Irwin also calls for more social science and more risk assessment. I enjoyed the way citizen science as Irwin describes it changed the power relationship between teacher and student.

This blog post is an excerpt from Dancing with Dugongs: Having fun and developing a practical philosophy for environmental teaching and research by Peter E. Oliver and William C. Dennison, which will be released at the 2013 Riversymposium in Brisbane, Australia.