"Raising the bar" vs. "Dumbing it down" for science communication

Bill Dennison · | Science Communication |We have long advocated "Raising the bar" for science communication products. We feel that complex ideas can be effectively communicated, as long as the language and visualizations are clear, concise and concrete. The communication specialists often advocate "Dumbing it down", reducing the complex to very simplistic terms, glossing over any complexities to form 'sound bites'.

Several of us at the Integration and Application Network are reading the book "Made to Stick" by Chip and Dan Heath (Random House, 2007). This book addresses the issue of how to make ideas 'stick'--that is, resonate with the audience, maintain their integrity and influence future actions. A passage in the book regarding this topic is particularly poignant:

Several of us at the Integration and Application Network are reading the book "Made to Stick" by Chip and Dan Heath (Random House, 2007). This book addresses the issue of how to make ideas 'stick'--that is, resonate with the audience, maintain their integrity and influence future actions. A passage in the book regarding this topic is particularly poignant:

“It’s hard to make ideas stick in a noisy, unpredictable, chaotic environment. If we’re to succeed, the first step is this: Be simple. Not simple in terms of “dumbing down” or “sound bites.” You don’t have to speak in monosyllables to be simple. What we mean by “simple” is finding the core of the idea.”

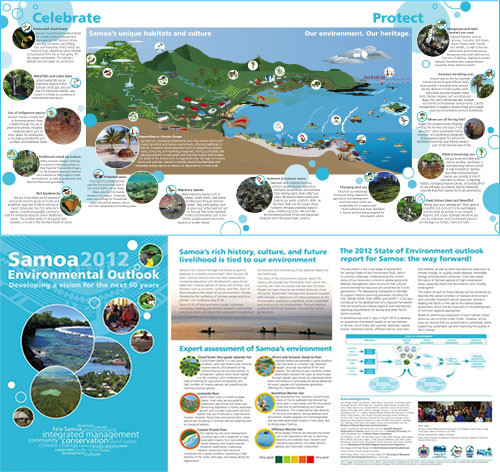

This "finding the core of the idea" that the Heath brothers describe in "Made to Stick" is what IAN Science Integrators and Science Communicators do in our storyboard sessions to develop science communication products. We establish a primacy of information and establish the most important concepts, and then create active titles that summarize the concept and select the photographs, maps, conceptual diagrams, figures, tables and text to support that concept.

The tactic of "Three Ways" described by the Heaths is a useful way to establish the central concepts. They refer to the "Curse of Knowledge" as the intellectual baggage that people often carry which creates erroneous assumptions about what the audience already knows. The exercise they describe is where you attempt to tap out a tune just using a coin on a table, so the listener only hears the rhythm without any tones. The person tapping the tune is 'hearing' the tune in their head, but the listener is not. The person tapping cannot understand why the listener has so much trouble interpreting the song, but it is because the listener is not privy to the tune. This is an example of the "Curse of Knowledge". The Heaths write the following:

"This tactic of the 'Three Whys' can be useful in bypassing the Curse of Knowledge. Asking 'Why?' helps to remind us of the core values, core principles, that underlie our ideas."

We often use the successive questioning, beginning with "Who?", "Where?", "What?", "When?", and "How?" in order to ask "Why?" to elucidate the essential elements for our communication products. The "Why?" question is where good science needs to be employed for answers and good science communication needs to employed for dissemination.

Another point that the Heath brothers raise is that of "Commander's Intent". It refers to the management strategy in the U.S. Army where the goals of objectives of the various deployments are communicated to the troops so that they can adjust and adapt to changes in conditions without a precise battle plan to follow. The recognition that various battle plans are invariably rendered obsolete rapidly in battlefield situations means that improvisation will be necessary. The quote from "Made to Stick" is the following:

"Commander’s Intent. It’s about elegance and prioritization, not dumbing down.”

One of things that I gleaned from reading "The Autobiography of General Ulysses S. Grant: Memoirs of the Civil War" was Grant's ability to use handwritten notes delivered by hand to various officers to effectively communicate his "Commander's Intent". He wrote very unambiguous orders, focusing on his intended outcomes rather than prescribing methods or allowing for ambiguity as to his intent. It requires what Grant referred to as "Moral Courage" to make these decisions and commit to them on paper.

In summary, having the courage to find the core of an idea through careful questioning, and develop unambiguous statements is essential in creating elements of successful science communication.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.