Scientists Alone Won’t Save the Earth

Tan Zou · | Science Communication | Applying Science | 10 commentsBy: Tan Zou

Solving an environmental problem without creating new problems is not always as simple as unlocking a door with a key. Even if it is, scientists cannot always do it all by themselves. As Erle C. Ellis points out in his New York Times article, everyone is struggling for a better life defined by themselves, and sometimes there is no single optimal solution to satisfy all. In the age of humans, often referred to as the Anthropocene, experts and their scientific narratives should no longer be "at the center of decision making," because what we want to realize is a better future for all people and institutions, including but not limited to scientists and science.

The lecture started with a discussion of last week's blog and students' final projects. For our final project, students will work in small groups to prepare and present a group research proposal that discusses approaches to integrate cultural and natural resources for national parks in the National Capital Region. This final project will be good practice for students to apply some of the theoretical and applied social science approaches that we learned and will continue to learn in this class.

The lecturer of this week, Dr. Bill Dennison, is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES). Professor Dennison started his career as an ecologist studying seagrass and discovered a novel phytoplankton bloom (brown tide). Later, his career path was influenced by his postdoctoral fellowship at Stony Brook University and then he devoted his career to not only natural research, but also to scientific integration and application.

Before discussing any possible solutions for environmental problems, we need to first classify the environmental problems themselves. Dr. Brian McIntosh and Dr. Dennison discuss in a blog that environmental problems can be identified as: 1) simple, complicated, or complex problems; 2) puzzles, problems, or messes; and 3) tame, wicked, or super wicked problems. Environmental problems that are not easily resolvable can be complex or wicked problems, or even messes. Some simple or tame environmental problems may not even need integration beyond the field of environmental science, but science alone cannot always solve complex problems.

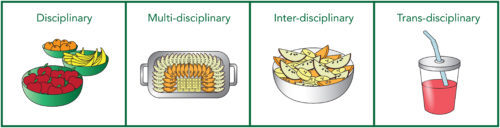

One possible approach to addressing complex and super wicked problems, or messes, is transdisciplinary research. As defined by Carolina Adler, transdisciplinary research is "an approach to understanding and solving societal problems by bringing together different knowledge streams". The word "transdisciplinary" is usually compared with three other terms: disciplinary, multidisciplinary, and interdisciplinary1. A variety of different definitions are available for these terms. For example, Jahn et al. proposed a comprehensive framework for transdisciplinarity in 20122. During the class, we discussed the differences between multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary. With Dr. Dennison's and Suzi Spitzer's help, we understood that one difference is that multi-disciplinary research only involves academics, while transdisciplinary research involves non-academic participants.

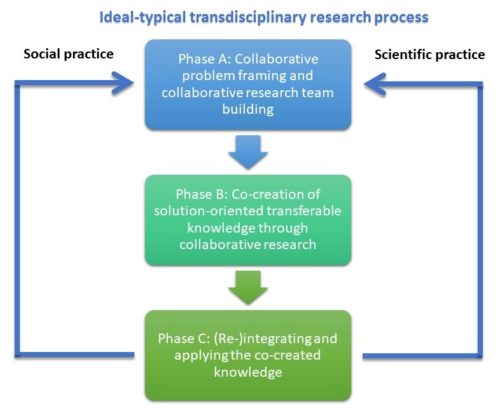

How can we conduct transdisciplinary research? Lang et al.3 developed a conceptual model that describes three phases of an ideal-typical transdisciplinary research process, adapted from multiple similar models in the literature. In their paper published in 2012, they discuss the design principles, challenges, and possible solutions of each phase, using illustrative sustainability project examples in Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Asia. Transdisciplinary research always involves a mutual learning process within stakeholder groups, and Roux et al.4 discuss three key questions that need to be answered during the process: ''who to learn with'', ''what to learn about'', and ''how to learn''.

Theories and models of transdisciplinary research in the literature are sometimes too abstract and simplified, thus further discussions on the conceptual model's realization are necessary. Some of the key factors for successful transdisciplinary research are a collaborative team that is representative of all stakeholders, effective participation, communication, and understanding. These were the major topics of our discussion in the second half of the class. At the beginning of any transdisciplinary research project, we always need to identify key stakeholders, enter their comfort zones, and invite them to join the study. Using our final course project as an example, important stakeholders of the National Park Service research include not only natural resource managers and researchers, but also park staff, park visitors, people living in the neighborhoods, and more. Dr. Dennison also mentioned, based on his experience, that it is important to involve all stakeholders in the project at the very beginning, and passion can work more effectively than empathy for engagement and problem-solving.

Communication skills are essential for transdisciplinary research. Unfortunately, cultivating these skills is not always part of our scientific training. The communication within a collaborative team is a two-way process among different groups of stakeholders. Even though this process can be more expensive and time-consuming than traditional one-way communication, it helps us achieve both desired research and societal outcomes. Dr. Dennison shared with us some communication tips that he has found useful for improving engagement, such as taking group pictures and mentioning people's names under the pictures. Communication does not only happen during team meetings. Sometimes great ideas, as Dr. Dennison mentioned, appear during breaks.

The purpose of communication should not be to persuade, but to understand stakeholders who are different from us. The cultural models and cultural consensus analysis taught last week by Dr. Michael Paolisso, are two effective approaches for understanding. For example, if you do not understand watermen's reasoning about blue crab management, you will not be able to find the right language and figure out the right avenues for collaboratively solving the problem of declining crab population. Another example from my personal experience is low-income people's food choice in Los Angeles. It had been hard for us working on a food justice project to understand why many low-income people had unhealthy diets. In the beginning, we thought it was due to their ignorance. After several interviews, we realized that for some workers, eating meat was the fastest way to gain enough energy before heavy work, and for workers who could hardly find time to cook at home and who did not have access to a kitchen at the workplace, they had no better choice than buying and eating fast food. What I leaned from that project is that the ignorance was sometimes not in the communities scientists work with, but in us.

In class, we also discussed possible obstacles to transdisciplinary research in the United States. The group gave examples such as political polarization, lack of belief in science-based decision making, and the difficulty of assembling a team that is truly representative of all stakeholders. Another possible obstacle is that scientific research process is full of doubts and debates, while in the real world what may be desired is a simple and quick answer.

Not all the challenges that transdisciplinary research currently faces were covered in the class, and there are more details to be discussed and clarified if we want to apply this approach successfully. Besides what is given in Jahn et al.'s definition, transdisciplinary research also emphasizes the equal rights to the pursuit of a better future. To realize the rights, I would suggest all stakeholders do John Rawls' thought experiment of the "veil of ignorance" when they start working on a transdisciplinary sustainability project. Stakeholder groups should include scientists, but we must remember that scientists alone won't save the Earth, because not only scientists live on Earth.

References

1. Stock, P.; Burton, R.J. Defining Terms for Integrated (Multi-Inter-Trans-Disciplinary) Sustainability Research. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1090-1113.

2. Jahn, T.; Bergmann, M.; Keil, F. Transdisciplinarity: between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecological Economics 2012, 79, 1-10.

3. Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M. et al. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science 2012, 7(Suppl 1): 25.

4. Roux, D.J.; Nel, J.L.; Cundill, G. et al. Transdisciplinary research for systemic change: who to learn with, what to learn about and how to learn. Sustainability Science 2017, 12: 711.

Next Post > Parramatta River Study Tour

Comments

-

Jessie Todd 7 years ago

I think you have written a well-rounded blog. We had a lot of content last week. Near the end of your blog, you mentioned that communication is not meant to persuade, rather understand stakeholders that are different from us. I agree with learning to understand differences among groups, but I might add to that statement "inform". I would argue communication to different stakeholders does a big job of informing different groups of knowledge that everyone needs to understand to really get down to the nitty, gritty and solve those wicked problems. Communication is such a key element in solving major environmental problems.

-

Srishti Vishwakarma 7 years ago

Nice job, Tan. I really liked your blog, and how you have connected the ideas of class. A very simplified summary of transdisciplinary.

You said a great point that "Identifying key stakeholder is important." This is true in any field of science. Also, communication is the key to everything. If we are not sharing our ideas and problems to these stakeholders, then they might not get acquainted with our viewpoint for an issue. Expanding the circle of transdisciplinary might be difficult initially. But once we are through it, we can achieve many more goals which are healthy for a society.

-

Alexander Sahi 7 years ago

I think that transdisciplinary research is an important step for ward for integrating multiple stakeholders, including extra scientific actors, into discussion with each other. As I learned in a workshop last night, it is not always necessary to agree with each other in these types of research situations. Transdisciplinary research can help illuminate that, and show that just because not everyone agrees with each other does not mean that a common goal/purpose is not shared.

-

Auzef Soruları 7 years ago

I strongly agree with you. Science needs the scientists of the universe we live in. This need is increasing day by day. Hopefully one day the world becomes more livable. Thanks.

-

Morgan Ross 7 years ago

Excellent description of our class discussion. I appreciate how you presented the material clearly and then linked it to your practical research observations. As we continue to become a more globalized community, transdisciplinary work will likely become widely used. Your proposed definition/purpose of transdisciplinary work is derivative of the ideals of sustainability. I can see how transdisciplinary methods can be used to create a more sustainable future. Wonderful post.

-

Brendan Campbell 7 years ago

Maybe I'm pessimistic but I feel that most environmental problems fall in the 'super wicked, complex, mess' category, which has to be the perfect phrasing for this topic. No one person has the capabilities of solving these problems alone which highlights the need for these trans-disciplinary approaches. Between the complexity of the natural systems and the varying different social systems that can be involved with any given environmental problem, there needs to be some common ground between all members of interest to progress towards a solution. I think one thing to note though is to what point are there too many 'cooks in the kitchen' and the problem cannot be solved? Is there a threshold that can be crossed that impedes forward progress? Can that threshold be defined?

-

Brian Scott 7 years ago

NIce content, Tan. You brought a lot more to the discussion than we got to in class. I sat up in my seat when I saw your first graphic. Good choice.

Brendan's comment also made me think...it's true that many environmental problems are complex and messy. However, I think many are not complex at all, and have easy solutions. WHether or not we have the will to implement those solutions is another matter. Transdisciplinarity sometimes may mean just getting people together to see that there are obvious solutions we can agree on. We solved smog in Los Angeles, acid rain on the east coast and stopped using ozone destroying chlorofluorocarbons in our refrigeration units. Those were not science-only solutions (although the science was a big help).

-

Shannon Hood 7 years ago

I really enjoyed this class and appreciate the framework that this approach provides for an inclusive approach to learning. I was confused by the differences among multi/trans/inter-disciplinary styles and found our in class discussion to be helpful. I also love the fruit analogy you provided in your blog.

Communication skills, as you mention, are critical to a transdisciplinary approach. How we speak (and listen) is just as important as what we say (and hear).

-

Natalie 7 years ago

Nice job Tan! Although we didn't get a picture of Bill will swollen eyes, you summarized the course well.

I am intrigued by the discussion between Brendan and Brian about the use of transdisciplinary. I am glad that Brian raised the point that this could actually provide some obvious solutions when everyone is working together. However, as great as that is, I think Brendan's point and the point in our readings is that these complex wicked problems can't be fixed with one discipline alone.

-

Alana Todd-Rodriguez 7 years ago

I'm glad you mentioned the necessity of involving all stakeholders in a project from the very beginning. I saw that as one of many main points of transdisciplinary research, and the best technique for successful outcomes of research and projects. Part of this does deal with communication, and maybe it is worth universities requiring courses that give new researchers the necessary toolkit for effective communication. You framed these concepts really well. Good job!