Scientists underwater: Reginald Truitt, Gilbert Klingel, the Bentharium and the Aquascope

Bill Dennison · | Science Communication | 1 commentsCelebrating 90 years of UMCES series

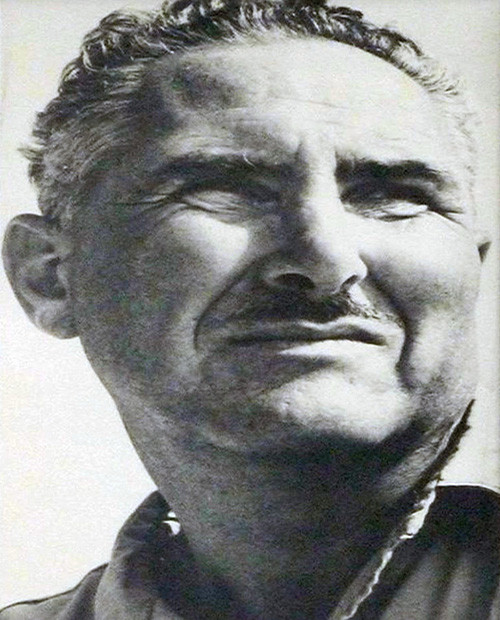

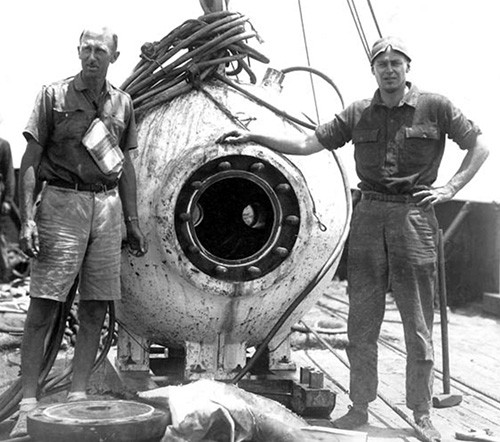

As I was looking through the newspaper clippings and photographs of Reginald V. Truitt, founder and first director of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, I was intrigued by a photograph of Truitt standing in a metal hatch protruding from the water and shaking hands with another gentleman. On the back of this photograph, the following words were inscribed "R.V. Truitt & Gilbert Klingel" and "Developers of the Bentharium" along with the year "1935". I had already begun to learn how impressive Reginald Truitt was in so many aspects of life, but what was he doing in this thing called a "Bentharium" and who was Gilbert Klingel?

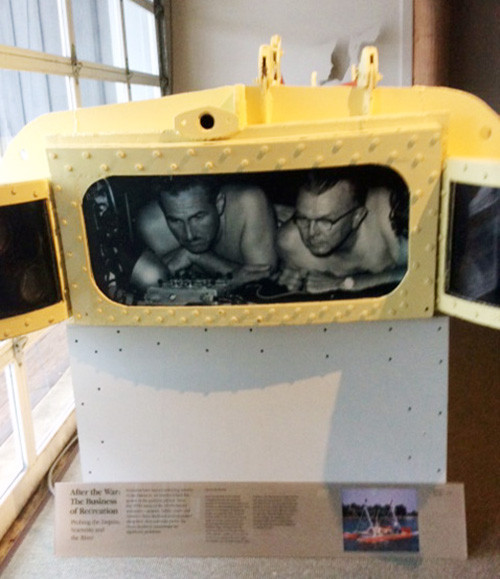

I visited the Calvert Maritime Museum and discovered an underwater device known as the "Aquascope" with a photograph of Gilbert Klingel (1908-1983) and another man peering out of the portholes in the front. The sign said that the Aquascope had replaced the Bentharium, so I began to look for information about how Reginald Truitt and Gilbert Klingel had developed the Bentharium and what they had seen when they gained their first underwater views of Chesapeake Bay.

I was able to meet Robert Hurry, the Archivist at the Calvert Maritime Museum, who has a model of the Bentharium in his office. He pointed out the bulkhead on the museum grounds where the Bentharium was buried as fill after it was decommissioned. Robert provided me with some back issues of the museum publication 'Bugeye' in which the Bentharium was discussed. He also pointed me to Klingel's book, The Bay, in which the Bentharium was described.

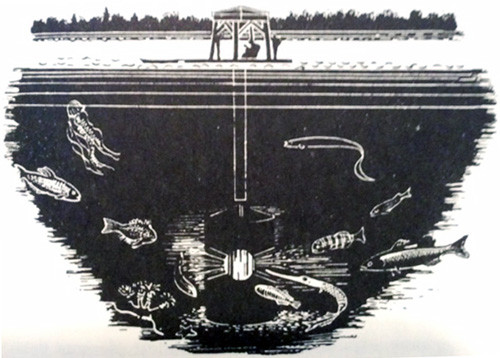

The Bentharium was a modified steel boiler that housed two people and was lowered from a specially constructed barge and winch system. It was the brainchild of Reginald Truitt and Gilbert Klingel. While talking with Reginald Truitt's daughter Trudy Truitt Guthrie, I learned that Truitt, in spite of his athletic prowess, was claustrophobic and after testing out the Bentharium, declined to descend and instead his adventurous wife Mary descended with Gilbert Klingel. The Bentharium measured six feet six inches by four feet and used a thick quartz glass porthole. Sand was used as ballast.

In Gilbert Klingel's 1951 book, The Bay, he describes the inception, construction and observations in the Bentharium. Klingel wrote "Dr. Truitt offered the facilities of his, then new, laboratory and the men of the society [Natural History Society of Maryland] contributed materials suggestions and labor." He also wrote the following about the launch of the Bentharium: "The Bentharium was built in a little creek at Solomons Island, Maryland, and when the motorboat arrived early one sunny morning to tow us into the broad reaches of the Patuxent River for the first trial, I am sure that the then-peaceful bayside village had never seen such a queer contraption pass through its pleasant little harbor. The Solomons Islanders, for the most part, were noncommittal, but a goodly number were quite certain that before long there would be first-class drowning."

Klingel also wrote about the observations that he made from the porthole of the Bentharium. They made descents during the day, at night using lights and they would also take down some bait to attract fish and shellfish. Air was supplied through a tube that reached the surface and a separate exhaust line was used to create a flow through system. Klingel wrote that the air quality was so good that you could smoke a cigarette in the Bentharium, which is a reflection of the time (1930s), but astounding nonetheless.

Klingel's book, The Bay, is a very nice accounting of his observations of Chesapeake Bay. It was reviewed for the New York Times in October 1951 by none other than Rachel Carson. She wrote the following about Klingel: "He has observed events below the dark green waters of the bay, through the glass face-plate of a helmet and through the windows of a diving device called a bentharium. With the endless patience of a true naturalist he has recorded the details of the pageant of life enacted by jellyfish and fiddler crabs and barnacles and all the rest of the bay's creatures."

It is important to consider that the early 1930s were when the depths of the ocean were largely a mystery. SCUBA (self contained underwater breathing apparatus) had not yet been invented so the only underwater scientific forays were using diving helmets or bulky and cumbersome hard hat diving gear. These techniques were quite limited in scope and the divers were relatively immobile and uncomfortable. The 1930s were also during the Great Depression, so funds for ocean exploration were hard to come by. William Beebe (1877-1962), a naturalist based at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, was an exception, and he was able to raise money and partner with Otis Barton to build the Bathysphere, a steel sphere with portholes that was lowered by cable to 3,000 feet below the surface off Bermuda. Beebe provided live radio broadcasts and wrote a book, Half Mile Down, about his exploits. So Truitt and Klingel along with Beebe and Barton were at the leading edge of ocean discovery.

Klingel was able to use his experience in the Bentharium to convince the National Geographic Society to fund the construction and operation of a successor to the Bentharium that he called the Aquascope. The Aquascope was built in 1954 and allowed two people to lay down and look out through a large viewing window and could be used to depths up to 100'. Chesapeake Bay is largely shallower than that depth and this allowed the Aquascope to provide access to the vast majority of Chesapeake Bay. Klingel wrote an article for National Geographic and the photo that is displayed in the Aquascope which is now at the Calvert Marine Laboratory includes Klingel and Willard Culver, a photographer from the National GeogGraphic Society.

It is interesting to reflect on the massive changes that have taken place since Klingel and Beebe were having themselves lowered underwater. The desire to gain an underwater perspective has been greatly enhanced with scuba diving and underwater videos carried by ships or by drones. To be among the first humans to explore the underwater realm must have been fascinating and it is nice to know that Chesapeake Biological Laboratory scientists were at the forefront of this effort.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Next Post > Mackay Report Card Workshop – Mackay, Queensland Australia 24 February 2015.

Comments

-

Melissa D. 11 years ago

This is very cool to think about. It's great that those great ideas were able to become a reality! Now I must revisit the Calvert Marine Museum to check things out.