Ten teaching tips from the Teaching & Learning Transformation Center at the University of Maryland

Suzanne Webster · | Science Communication | 1 commentsScience communication professionals at IAN regularly assume the roles of teachers when we develop semester-long courses, create science communication products intended to inform and engage diverse audiences, and facilitate collaborative workshops on a variety of topics all over the world. We recently reached out to education specialists Marissa Stewart and Andrew Webster from the Teaching & Learning Transformation Center at the University of Maryland College Park (TLTC) to help us learn how to be more effective instructors.

The following ten teaching tips are my takeaways from the workshop:

1. Emulate the qualities of your favorite teachers

At the start of the workshop, we were asked to describe our favorite teachers. Collectively, we named a wide variety of traits of teachers that were particularly effective or inspirational. Teachers made an impression on us when they were excited about their subject material, supportive of their students even when they made mistakes, approachable as a human, and able to explain concepts in creative ways. It is important to learn from those we respect, and emulate the traits that we most admire in our own teaching, but also keep in mind that not all teachers need all of these pieces. One person can't be all these things to all people at all times!

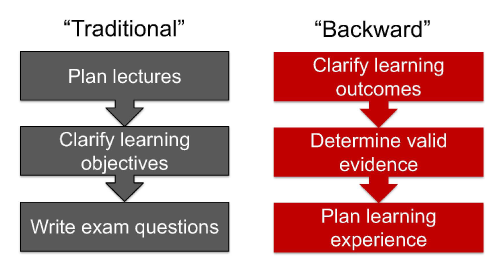

2. Design learning opportunities from the end, rather than the beginning

The traditional approach to designing a course or activity is instructor-centered and focuses on how material will be presented. In order to avoid the pitfalls of this approach, such as over-inundation of information, effective teachers instead adopt backward design, which is student-centered and emphasizes learning outcomes. Backward design requires teachers to prioritize consideration for the end result of the learning opportunity, rather than the finer points of the learning process or content. Teachers should begin by asking themselves probing questions, such as "What do I want my students to remember 10 years from now?" and "What should my students be able to do by the end of this opportunity?" This is similar to our motto in science communication or persuasive writing, in which we consider what it is that we want our audience to learn, rather than what we want to tell them.

3. Develop learning outcomes

Learning outcomes are the intended results of the learning process. They are scalable, so they can be developed for learning opportunities of all sizes, from graduate programs all the way down to single lectures or workshop activities. In contrast to instructor-centered course objectives that specify the intended result of instruction and focus on the role and responsibilities of the teacher, learning outcomes are student-centered and should focus on measurable skills that students ought to take away from a learning opportunity. Defining specific and transparent outcomes helps teachers create a road map for their course and provides a framework to use when making decisions about course development. Specific outcomes also help students understand what they should expect from a learning opportunity.

4. Use Bloom's taxonomy to articulate effective learning outcomes

There are many sequential levels of learning that characterize different levels of content mastery and application, from simple and straightforward skills such as gaining knowledge on a particular topic, to complex tasks that require more involved cognitive processes. Teachers should identify which levels they expect their students to reach, and use Bloom's action words to articulate specific learning outcomes. At IAN, we often begin workshops working towards learning outcomes that involve simpler cognitive tasks, such as "selecting" effective images and "identifying" the values and threats of a socioecological system. Over the course of a class or workshop, we build upon these skills into higher-level outcomes that ask students and participants to "develop" report cards or "create" conceptual diagrams, for example.

5. Assess student learning along the way

Assessments give students feedback on their learning while also providing the instructor insight into their students' progress towards achieving learning outcomes. Formative assessments are low-stakes assignments and activities that monitor student learning throughout the learning process. Some examples of formative assessments that we use at IAN are weekly critiques on individual assignments in the Science Visualization course and comments on conceptionary masterpieces during Science Communication workshops. Incorporating several formative assessments into teaching allows students to test their knowledge and receive real-time feedback, while also giving teachers an idea of their students' progress towards mastering the content.

6. Include a diversity of active learning activities

Long-term learning requires engagement. Teachers can engage learners by incorporating various active learning activities into their lessons. Activities should be designed to help students achieve learning outcomes, but should also provide the instructor with a measure of whether or not learning is occurring. Examples of active learning activities include think-pair-share discussions, focused listing, and concept mapping. At IAN we rely on these types of activities to collaboratively develop products with stakeholders, such as word clouds, stakeholder maps, and conceptual diagrams.

7. Create a balance between information quantity and quality

When designing a course or workshop, teachers must navigate the tradeoff between content and mastery when making decisions on how to make the best of their limited time with students. The Latin proverb, "Repetition is the mother of all learning," reminds us that in order for long-term learning to occur, students must have multiple opportunities (at least three) to interact with any given content. If students are given too much content to learn in a fixed amount of time, there will be limited opportunities for students to master skills and ingrain new knowledge.

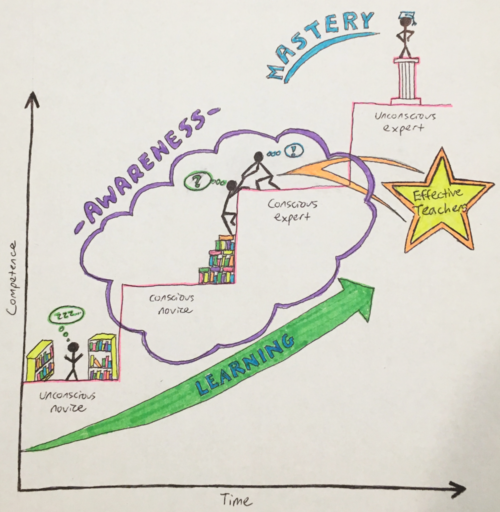

8. Be mindful of the stages of learning

Learners progress through four sequential stages when mastering a new skill. A 'blissfully ignorant' unconscious novice becomes a conscious novice when they gain awareness of their own incompetency. After acquiring and practicing a new skill, they become a conscious expert because they have learned the skill but remain cognizant that others don't necessarily share the skill. Over time, masters become unconscious experts who are effortlessly competent but have lost awareness that others do not share their skill. Effective teachers are able to maintain conscious competence that allows them to be empathetic towards learners. Teachers should strive to be aware of what it is like to not know something and seek to provide knowledge and support as needed to help a novice master the skill themselves.

9. Seek out feedback on your teaching

Teachers can improve their teaching strategies and content by considering both positive and negative feedback. When requesting feedback from students and participants, ask specific questions about their knowledge or learning experience in order to obtain more detailed and helpful information. For example, instead of asking "What did you like or dislike about the course?" ask "What about the course helped you to (insert learning outcome here)?" and "What do you wish you could have learned in this workshop that was not covered by the instructor?" For additional perspective, elicit feedback from peers and supervisors, hire outside consultants, and don't forget to invest time into personal reflection. It is crucial to receive feedback from multiple people in various positions because people experience your teaching in diverse ways and draw from different areas of expertise when offering compliments and constructive criticism.

10. Remember that "teaching is never done"

Like science, teaching is an iterative process that requires apprenticeship, reflection, and repetition. As teachers, we must learn from those whom we admire, be self-aware of where our weaknesses lie, and embrace a growth mindset and an eagerness to continually update and improve our techniques as we become more experienced.

Our IAN team will undoubtedly incorporate many of the techniques and ideas that we learned from this workshop into our upcoming semester-long classes, workshops, and other teaching opportunities. These tips will also serve us well in our more indirect teaching roles as science communicators, as we develop communication products that are designed to share knowledge with diverse audiences. Thank you again to the Teaching & Learning Transformation Center for a productive and enlightening professional development experience!

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.

Next Post > Science Cafe and science communication training in Boston

Comments

-

Pat Harcourt 8 years ago

This post gives excellent advice for how to approach the complex task of teaching. I especially applaud the focus on the learner, since learning is an active process where the learner must be engaged and the material must be presented at an appropriate level for the learner.

One note I would like to add is that the current standards for public science education focus much more on science and engineering processes than former standards did. Learners are challenged to consider phenomena from the natural world and to structure testable questions rather than only answering someone else's questions. They must make sense of data and propose explanations based on evidence. When the data are those collected by the learners themselves, they are eager to dive in and look for patterns.

A favorite quote of mine is "education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire"(William Butler Yeats). Let's share our passion for science and inspire all our learners!

-Pat Harcourt, MADE CLEAR