Visiting the Nickel Preserve in eastern Oklahoma

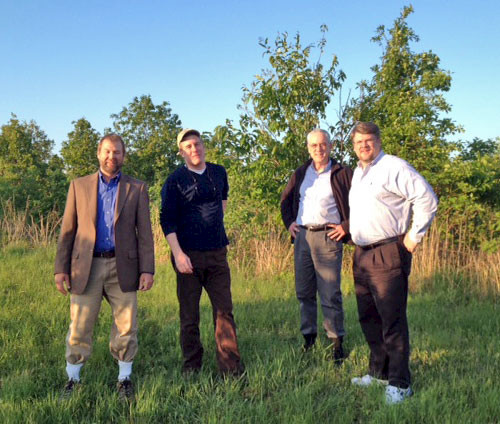

Bill Dennison · | Science Communication |As a follow up to the Arkansas/Red River workshop in Tulsa, OK where we facilitated a workshop associated with the development of a Mississippi River report card, five of us traveled to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) Nickel Preserve in Eastern Oklahoma. Jordy Jordahl, the Executive Director of America's Watershed Initiative, Patrick Brennan, the Sustainability Manager from Ingram Barge, along with me, Heath Kelsey and Bill Nuttle from the IAN team comprised the report card strategy group. The route to the Nickel Preserve took us past the McClennan-Kerr Navigation System, the subject of much of our workshop on the Arkansas River. We also traveled through some small rural towns and gravel roads that were reminiscent of rural Appalachia.

The Nickel Preserve is located in the Ozark Mountains near the Illinois River (same name, but different river than its counterpart in the state of Illinois). The headquarters for the Preserve is in a beautiful log house, complete with cathedral ceilings, a stone fireplace, wooden furniture, and beautiful nature photographs. We slept in bunk rooms adjoining the maintenance garage and had a beautiful, nearly full moon at night. We had a wonderful barbecue dinner delivered to the headquarters.

The Ozark Mountains are more hills than mountains, but provide for a unique geological backdrop to the Nickel Preserve. The Ozarks support a high biological diversity, enhanced by the diverse landscapes and the long stable geological history of the region. We hiked a nature trail along Pine Ridge where we could view the oak dominated forest on the north facing slope and the Shortleaf Pine dominated forest on the south facing slope. We learned that this is due to the fire ecology of the forest. The south facing slopes are drier due to the sun exposure and burn and experience drought more frequently than the south facing slope forests. The Shortleaf Pine trees are a fire tolerant species and they were the dominant tree when the early explorers arrived. Fire suppression by settlers has reduced the natural savanna type landscape that was dominated by prairie grasses and Shortleaf Pine trees. TNC is attempting to restore the 17,000 acre tract of land to its original vegetation. We noted that the soil is relatively thin and the trees were rather small.

We also hiked a trail in the savanna, which was more open canopy, but the grasses we hiked through were great habitat for ticks. We ended up returning absolutely covered in ticks, including wood ticks and the lodestar tick. We all ended up stripping off our clothes outside and jumping into the shower and changing into fresh clothes when we returned to the headquarters. We enjoyed talking with Jeremy Tubbs, the Preserve manager, about their reintroduction of elk, invasive plant control and developing a tall grass prairie community. We saw a coyote, lots of birds and, already mentioned, lots of ticks.

The purpose of our mini-retreat was to develop a strategy for the Mississippi River watershed report card release at the upcoming Mississippi River Summit in Louisville, KY on Oct. 1–2. We were able to develop a timeline for the report card completion, concocted some ideas to insure that we engage the audience, and discussed the long term strategy for developing commitments to improve the Mississippi River watershed, based on responses to the report card. We likely could have held this strategy session in Tulsa, but the change of venue and the opportunity to observe these unique ecosystems was well worth the trouble. We needed to switch gears from running a series of large workshops to developing a series of webinars, smaller, targeted meetings and producing the report card. The change of venue helped us make the transition.

It is an interesting challenge to come up with strategies for living up to our Integration and Application Network tag line: "Communicate better. Empower change." Thus simply engaging experts in workshops, accessing data, crunching the numbers and developing a transparent reporting scheme and then effectively communicating the results is not enough. We need to take it a step further and figure out how to effectively engage the key stakeholders in the Mississippi River watershed to act on the report results and develop the commitment to achieve the goals that the report card is designed to measure progress on: water supply, navigation, economy, flood control, ecosystems and recreation. Our mini-retreat helped us begin this process, in partnership with the various partners in America's Watershed Initiative.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.