We are Trailblazers: The Chesapeake Bay Program in 2019

Bill Dennison ·

As part of the “Rounding the Curve on Adaptive Management” meeting in Richmond, VA, I gave the opening plenary talk. Kristin Saunders told me that the title and topic of the talk should be “We are Trailblazers”.

The term “trailblazer” is described well by Ralph Waldo Emerson who said “Do not follow where the path may lead. Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.” The first time “trailblazer” was found in print was in a Montana newspaper: “The merchants thereupon, desirous of securing the trade of the new mines, offered the stranger $100 if he would blaze a trail through, and afterward it could be cleared sufficiently for pack animals to pass along.” (Helena Independent, 1883). The Oregon trail, which stretches from Missouri to Oregon, has led to the Portland, OR basketball team in the National Basketball Association to be named the Portland Trailblazers. So the word “trailblazer” is a relatively recent word with its origins in America.

Another use of the term “trailblazer” was used in World War II, beginning in 1943 by the U.S. Army 70th Infantry, which trained in Camp Adair, Oregon. My father, John B. Dennison, was stationed at Camp Adair and his unit was shipped to France in December, 1944. The Trailblazers were sent up to the front along the France/Germany border in the Alsace region. As part of the Ardennes/Alsace German offensive, known as the “Battle of the Bulge”, my father was wounded in Feb. 1945. This turned out to be fortuitous, as he was sent to a Paris hospital, thus avoiding severe casualties in his unit in early 1945. My father rejoined his unit in early April and the European war was over a month later. These heroic trailblazers are worth emulating in any way possible.

The question of how the Chesapeake Bay scientists and resource managers served as trailblazers was addressed. The current Chesapeake Bay Program logo includes the words “Science, Restoration. Partnership.”, and trailblazing has occurred in all three aspects of the partnership.

Trailblazing science: Estuarine science was essentially conceived in Chesapeake Bay, with the physics of two-layer circulation described in the James River (I pointed out that the James River was a short walk from the meeting location) by Don Pritchard from the Chesapeake Bay Institute, Johns Hopkins University. The biology of Chesapeake Bay was described by scientists like Reginald Truitt, Romeo Mansueti, and Gene Cronin from the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, now part of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. The Atlantic Estuarine Research Society, founded by Chesapeake scientists, expanded and eventually formed the international Coastal & Estuarine Research Federation. The scientific journal Chesapeake Science eventually became Estuaries and Coasts.

In 1972, Tropical Storm Agnes broke an extended dry period and created a massive flow event. The leaders of the three major research institutions, Bill Hargis (Virginia Institute of Marine Science), Don Pritchard (Chesapeake Bay Institute; Johns Hopkins University) and Gene Cronin (Chesapeake Biological Laboratory) deployed researchers to assess the impacts of Tropical Storm Agnes. The results from these studies were published in a book by the newly formed Chesapeake Research Consortium. In the 1970s, a suite of observations led to concerns that Chesapeake Bay was undergoing a major environmental degradation. Maryland Senator Charles “Mac” Mathias initiated a comprehensive study through the newly formed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This study served to demonstrate the crucial role that excess nutrients were being delivered to Chesapeake Bay. This led to the formation of the Chesapeake Bay Program, described in my tribute blog about Governor Harry Hughes.

Another scientific aspect that was trailblazing in Chesapeake Bay was the establishment of a physical model of the Bay. The initial large-scale model was housed in a Kent Island warehouse, but has been replaced by computer simulation models which include airshed models, watershed models, water quality models, hydrodynamic models and living resources models. Another trailblazing scientific effort was the development of an integrated monitoring program, with both watershed and Bay monitoring programs initiated in the mid-1980s and continuing until the present.

Trailblazing restoration: The development of innovations in sewage treatment processing have been occurring in the Chesapeake region for decades. The Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant serving Washington, D.C. was upgraded to tertiary treatment in 1983, becoming one of first large plants to achieve this level of treatment. Innovations at Hampton Roads wastewater treatment facilities, recent upgrades of the Back River Wastewater Treatment, Baltimore have continued this trailblazing.

Trailblazing partnership: The establishment of the Chesapeake Bay

Program with the federal government working closely with the states of

Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia and the District of Columbia to work

collaboratively was innovative in 1983. The Chesapeake Bay Program included

three advisory committees so that local government, citizens and scientists

would be directly involved with the restoration effort. The Chesapeake Bay

Program expanded to include the headwater states of New York, Delaware and West

Virginia. A novel partnership between research institutions within the

Chesapeake watershed known as the Chesapeake Research Consortium was

established in 1971. Additional institutions have been added to this

partnership, now including X organizations. A partnership of the legislative

bodies of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, known as the Chesapeake Bay

Commission, was established in 1980. This partnership allows state legislators

to align their actions to the benefit of Chesapeake Bay restoration.

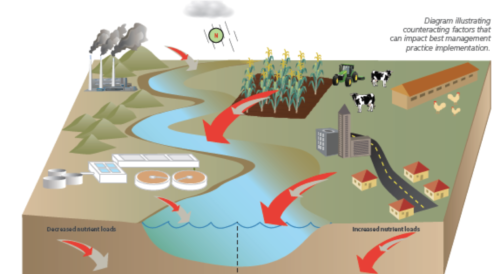

These historic trailblazing activities in terms of science, restoration and partnership continue to this day, but they will need to be accompanied by further trailblazing to tackle new challenges. For example, trialblazing will be needed to implement the 2014 Chesapeake Watershed Agreement, because it includes new challenges like expanding diversity in those who are involved in the restoration effort or incorporating climate change in the restoration efforts. The Chesapeake Bay Program will also need to trailblaze to fully implement an adaptive management approach, the subject of the Strategy Review System meeting that was the reason for this talk. The scientifically rigorous Chesapeake Bay Program report card produced by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science is being emulated globally, but an expanded report card effort to include ecological, social and economic indicators throughout the watershed has been initiated, which can be a trailblazing effort. The engagement of citizen scientists into the Chesapeake restoration effort is another trailblazing aspect of the Chesapeake Bay Program. The Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative is such an example, and they are working with a range of citizen science groups to develop protocols and training to bring in more citizen scientists. Significant progress in Chesapeake restoration has been made by upgrading sewage treatment and by cleaning automobile exhaust with catalytic converters and smokestack scrubbers. But the big remaining challenge is stormwater, both from urban impervious surfaces (roofs and roads) and from agricultural fields (excess fertilizer and manure). Trailblazing will be needed to partner with cites and towns to reduce urban stormwater runoff and will be needed to work with farmers to reduce agricultural runoff. To conclude this discussion of Chesapeake trailblazing, I like the quote by one of the original cowgirls, Dale Evans: “It’s the way you ride the trail that counts”. This is a reminder that it is the journey that counts and the learning by doing (adaptive management) approach that we embarked on is the way to ride the trail.

Additional credit: Lynch, M & G Sellner, K. (2005). AN UNPRECEDENTED SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY RESPONSE TO AN UNPRECEDENTED EVENT: TROPICAL STORM AGNES AND THE CHESAPEAKE BAY. (Photo 3 "Big Three").

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Next Post > Spanning boundaries at the Society for Applied Anthropology conference

Comments

-

Veronica M. Berounsky 6 years ago

This is great! What an informative blog! And its written in a style that is easy to read plus gets important points accross. The quotes are very good and appropriate.