You Can’t Spell Earth Without Art

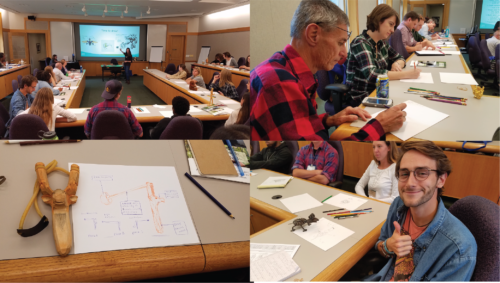

Emily Nastase ·It was really encouraging to see the room fill up for my session at the Chesapeake Watershed Forum on the Friday afternoon of November 3rd. The room seated 46 people, and nearly every chair was taken. I was holding not only the first session of the conference, but the first session I’ve ever taught, at the first conference I’d ever visited. I really wasn’t sure what to expect. My goals for the 45-minute time-slot were to demonstrate how the arts and sciences aren’t as different as people believe, to show how the two disciplines are used together, and to get my participants to “think like an artist” through a fun activity. How is all of this relevant to a room full of scientists?

Art is science. And science is art.

That’s probably not something you’ve heard before, right? But it’s true. Both art and science are human attempts to understand and describe the world. It is one of our primitive needs as humans to understand what’s around us and to share that understanding with others. This is something mankind has been doing for centuries. 40,000 years ago, humans made cave paintings. Whether it was to tell their stories, leave warnings for future generations, or document some religious practices, people have been communicating about the world around them through art far longer than through the spoken or written word.

If we fast-forward 37,000 years to the Renaissance era, we can find people actively combining the arts and sciences. The notorious “Renaissance man” studied not just one subject, but multiple disciplines, and often applied the skills learned from one subject to another. The Renaissance man was the first transdisciplinarian. Masters like Leonardo DaVinci, Michelangelo, Brunellischi, Galileo, and Machiavelli pioneered the crossroads between the arts and sciences – a skill we seem to have lost an appreciation for in the modern era.

Currently people seem to gravitate towards this idea that humans are either “left-brained” or “right-brained.” Left-brained people are those that are more analytical, logical, math-oriented, etc., while right-brained people are those that are more creative, artistic, and maybe operate on emotion rather than reason. That is total crap. We are all humans, and we all use all parts of our brains (although some sections more than others). This theory of a left vs. right-brained person is a misconception that supports the idea that the arts and sciences have very little overlap.

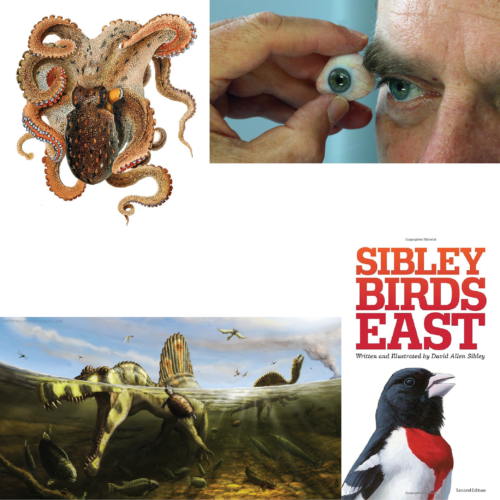

What many don’t realize is that the arts and sciences are being used together, and in many different ways. Some examples are scientific illustration, medical art, field guides and conceptualization.

And even in some truly weird ways: BioArt by Anna Dumitriu.

We also have some more practical applications of the arts and sciences together, such as conceptual diagrams, infographics, newsletters, and public outreach events.

All of these examples are great ways to use art as a learning tool, or to share scientific concepts with others. The beautiful thing about the arts is that they make for a wonderful engagement tool. This is something that proponents of “STEAM” programs (science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics) understand. Not only that, but communities already regularly engage with the arts, whether it be attending museums or movie premiers. So why not combine science with art to give the public a fresh perspective on research? Or even inspire new research?

The arts reach many people in communities who are not otherwise being reached. The arts are often the primary, and sometimes, the only motivation for some people to engage in a community activity or issue.

-Fiske, 1999; Kay, 2000; Volunteer Arts Network, 2005

The final aspect of my session involved an exercise. Like I said before, I wanted to get my participants thinking like artists. Together we made scientific illustrations of unique objects I had provided. The key to making a scientific illustration is that the artist must fully understand the subject they are trying to depict. Everyone was encouraged to thoroughly explore the object they were given - what does it feel like? Does it smell? What could this be used for? What is it made of? Why might it be colored the way it is? After analyzing the object, participants had to use a variety of techniques to communicate their intended message. Maybe they needed multiple images to describe their object. Maybe a cross-section was the best way to depict what the object was made of. Maybe a diagrammatic representation of the object in use was the best way to show the object and its utility. Unfortunately, participants only had 20 minutes to make their masterpieces. But even so they made some nice scientific illustrations!

After the session, my coworker Suzi and I celebrated with the biggest beers we could find.

All in all, I think this session was a great start to the Chesapeake Watershed Forum. For the rest of the conference I listened to and participated in others’ methods of engaging their communities about “Healthy Lands, Healthy Waters, Healthy People” – the forum theme from this year. It was well worth the trip to Shepherdstown, WV.

Image credits:

Untitled by Graeme Churchard, Flicker, 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Cathy Cheney, Portland Business Journal

, Wikipedia, public domain

David Allen Sibley, Sibley guides

Untitled, Samantha, Nature Walk Collection Sheet

Next Post > Mapping UMCES staff at CERF: A Fun Exercise in Networks and Impacts

Comments

-

Lou Etgen 7 years ago

Nice article Emily. Thanks for kicking off the Forum with a great presentation.