Following Alexander Bache’s Dream and His Example

Bill Nuttle · | Learning Science |"Scientists who made a difference" series

Earlier this month, Bill Dennison, Heath Kelsey and I attended a meeting at the headquarters of The Nature Conservancy in Arlington, Virginia, which is located just across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. We were there to discuss what will happen next after the Mississippi watershed report card is launched this spring. This project has challenged us to expand the report card format in two ways. First, we were working at a very large geographic scale – the Mississippi watershed includes all or part of 31 US states and 2 provinces of Canada. Second, the report card addresses a diverse set of issues – for example, it combines reporting on ecosystem health and the condition of transportation infrastructure. The report card’s scope is so inclusive that it will be difficult for any single existing organization to take it on. Designing a program capable of sustaining work to produce future versions of the report card requires some creative thinking.

Our meeting ended at noon, which left me with a couple of hours to kill before my train left for Montreal. It was a sunny day, clear but cold, so I decided to drop in on Alexander Bache, who spent a large part of his career directing the work of the U.S. Coast Survey. This would be a chance to re-acquaint myself with Bache’s work in collecting and analyzing data to map the coastline of the United States. As it turned out, my visit was quite stimulating in spite of the fact that Bache has been dead for almost 150 years. It got me thinking about similarities between the report card and the work of the Coast Survey and how the report card project might employ elements that Bache used to make the survey a success.

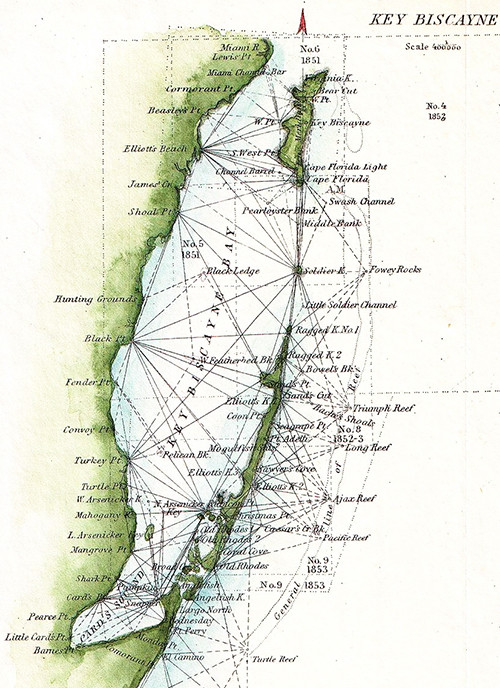

I first became acquainted with Alexander Bache a couple of years ago as the result of a discovery on a beach in Florida. I was visiting the historic lighthouse that marks the entrance to Biscayne Bay when something hidden in a copse of sea grape caught my eye. The object was a stone post, about 3 feet tall, apparently old and very out-of-place. The post was made of finely dressed granite, which means that it must have been transported there from 100s of miles away, because granite does not occur in South Florida. Carved on one side was the date 1855 and on another the letters “A.D. Bache.” The sign identified the object as a survey marker placed on Key Biscayne during the first expedition to map the coast of South Florida. The mapping was done by the process of triangulation, and this was one of a pair of monuments that marked the length of the baseline for the survey; the measured length of the baseline was used to calculate distances between all the points surveyed along the coast.

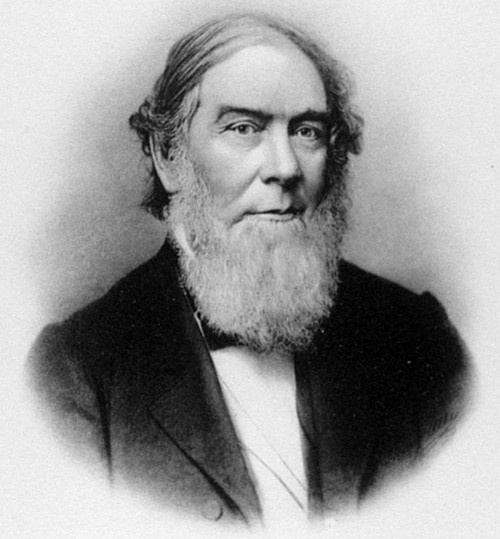

This discovery led me to find out who A.D. Bache was. Alexander Dallas Bache was a great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, born in Philadelphia on July 19, 1806. Bache’s family included influential leaders in national politics and administration and in civic affairs in Philadelphia. Philadelphia was a center of science and industry, and Bache was drawn into the less well-established profession of scientific research. Early in his career, Bache held a number of positions in and around Philadelphia in which he taught and conducted research. Later in his career, Bache directed his effort to combining science and public administration. Bache’s dream was that a healthy, vibrant American science community would catalyze progress, broadly defined to include an individual’s spiritual development and the perfection of society as well as material progress.

Alexander Dallas Bache was appointed as the second Superintendent of the US Coast Survey in 1843. President Thomas Jefferson established the Coast Survey in 1807 for the purpose of creating accurate charts to guide navigation. The Coast Survey was the first scientific program established by the US government. Charting the coast of the US while much of it was still wilderness was a technologically ambitious project. As with the program to go to the moon 150 years later, the technology required had to be created, and this stimulated a broad range of related scientific activities. Superintendent Bache was responsible for coordinating the logistics of the survey’s operations in the field, guiding the research and development of new instruments and methods of analysis, and sustaining the support in Congress required to keep the whole project moving. Under Bache’s leadership the Survey was the most important organization in American science.

The work of mapping the coast had to take into account the geologically dynamic nature of the coastline. Bache gave special attention to the task of mapping the treacherous coast of South Florida and he personally directed the exacting process of measuring the length of the baseline on Key Biscayne. This was a coastline like no other in the US, dotted with innumerable mangrove islands and surrounded by extensive shallow coral reefs, about which little was known. In particular, it was necessary to know how fast and in what ways the shallow reefs might change in the decades ahead during which the newly created charts would serve as authoritative guides to mariners. To address this critical gap in knowledge, Bache recruited the help of the world-renowned paleontologist Louis Agassiz, then at Harvard University. Agassiz’s study of the Florida reefs became a landmark in the discovery and exploration of coral reefs worldwide, in spite of being wrong about their origin and development.

Bache recognized that the work of the Coastal Survey was an investment in the human capital of the nation. The survey trained men in mathematics, astronomy and geodetic surveying and sent them into the field for months at a time required to carry out the exacting tasks of mapping. Bache came well-prepared to this task. Bache graduated from the West Point military academy, which provided him with the best education in science, mathematics and engineering available to anyone in the US at the time. Before joining the Coastal Survey, Bache led efforts to set up two new schools in Philadelphia intended to provide students with advanced training in science and technology. Bache toured Europe to study the approach taken by schools there that were the best in the world. While in Europe, Bache forged personal ties with leading scientists there, including Alexander Humboldt. Inspired by what he had found, Bache worked to build a vibrant scientific community in the US; these efforts resulted in the founding of both the National Academy of Science and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Alexander Bache died in 1867, and he is buried in the Congressional Cemetery, which is located southeast of the US Capitol building on the bank of the Anacostia River. To get there, I rode the Metro from downtown Arlington to the Potomac Avenue station. Then, I walked past a couple of blocks of renovated post-Civil War row houses, and through a wrought iron gate. Fortunately, I thought to ask directions at the cemetery office, because the coordinates I got from Google pointed to the wrong part of the cemetery. Bache’s tomb is more imposing than the granite marker I stumbled upon in Florida but less ornate than some of the other memorials. I read in the visitor’s guide that around me were “men and women who shaped the capital city and gave substance to the new nation”. Included are several who led expeditions to explore and map the Mississippi watershed and areas west.

The contrast between Arlington’s bustling downtown and the tranquil atmosphere surrounding Bache’s tomb mirrors the gap of 150 years that separates our work on the Mississippi watershed report card from Bache’s on the Coast Survey. Spanning that gap is the dream we share with Bache - that science can be a catalyst for progress. In the case of the report card, science is a double-acting catalyst. First, the report card gathers and analyzes data to measure progress with respect to each of 6 goals for the watershed. Providing a uniform measure of progress on all goals across the entire watershed will spark discussion and motivate action in geographic areas lacking in performance. Second, by scoring and reporting results for all 6 goals together, the report card will spark discussion of the interactions and interrelationships among goals that usually have been considered independently. And, this will promote a shared understanding of problems facing the watershed and a vision for its future.

Is Bache’s dream enough to assure the success of the report card project? Probably not. Fortunately, we also have the example of Bache’s leadership of the Coast Survey to guide us. Bache did three things that were critical to the Survey’s success and, therefore, worth emulating in the Mississippi watershed report card:

Support for related scientific research – Bache’s critics liked to point out that map-making is a relatively simple exercise in applied geometry. However, mapping the US coast at the beginning of the 19th century was a task that could not be accomplished with the available knowledge and surveying tools. Bache’s Survey supported research and development to close critical gaps in knowledge. Some of these activities included research not directly related to the mission of the Survey, as in the case of Agassiz’s biological research on the Florida coral reefs. The results assured that maps produced by the Survey were accurate, and they added to overall utility of the Survey’s work.

Nurturing a collaborative network - Bache built an extensive network of colleagues and contacts through his career, and this network was essential in supporting the work of the Survey. The network gave him access to talent, information and equipment that he could not have obtained solely within the Survey organization. He built mutually beneficial relationships with other scientific organization and with coastal communities, increasing the value and utility of the Survey’s work. And he mobilized the good opinion and support of his professional peer network when it was necessary to build confidence in Congress for the Survey’s work.

Attention to education and training –The work of the Survey required a high level of knowledge, mechanical skill, and self-reliance. Some, like Bache, came to the Survey having acquired these attributes elsewhere, through education abroad or service in one of the technological corps in the military. Bache saw the work of the Coast Survey as an opportunity to realize the benefits of science and technology for the nation by increasing the scientific literacy of its citizens. Therefore, many who lacked access to these pathways for training acquired their training on the job.