Northern Australia floodplains research workshop in Brisbane

Heath Kelsey · | Science Communication | Applying Science | Learning Science | Australian cities and waterways |I met Jane Hawkey in Brisbane May 18-19 to facilitate a synthesis workshop on floodplains research in Northern Australia under the National Environment Research Program Northern Hub (NERP Northern). Our goal is to piece together the larger story being told by individual research components. As always, it was exciting to learn more about a new ecosystem - although I've been here discussing these issues for several months, it's fascinating to get to a new level of understanding that only happens when a group of experts are in the room together. In this case, that next level was about the linkages of the Kakadu floodplains to the issues that the rest of Northern Australia will face over the next few decades.

Kakadu National Park is about 3 hours drive East of Darwin, and is the largest national park in Australia, at about 20,000 square kilometers, or almost the size of New Jersey. Except for the uranium mine on the middle of it, it's protected, so development pressure within the park presumably won't be an issue. However, research in Kakadu lends important insight into the potential development pressures that will continue to be a part of the discussion about sustainable development in Northern Australia. Kakadu is an ideal place to discover how these systems work, and what implications that has for other systems in the north, and potentially in the rest of the world.

Tropical floodplain river systems occur in equatorial South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Northern Australia. Australia's tropical floodplain river systems represent some of the last, large, free-flowing tropical floodplain river systems in the world, and are relatively un-impacted by development and large population centers. However, talk of water diversion and extraction for irrigation schemes and supplying new development centers is ongoing. Understanding how these systems function is hugely important to sustainably managing the inevitable development in the North.

The story being told by the research in Kakadu is one of connections, and new thoughts about how energy is moving through the system, the things that are likely to affect that, and the cultural implications to traditional owners of the land. Kakadu is managed jointly, by the commonwealth and by traditional owners; information provided by the research here is providing new recommendations for maintaining a healthy land. I've explored a few of these connections already in previous blogs, but the key things center around:

- Processes that support high biodiversity, like animal movement, hydrology, food webs, and productivity,

- Social and economic considerations like stewardship, cultural resources, and connections to land,

- Threats to ecosystems and cultural resources from invasive weeds, feral animals, sea level rise, and land development, and

- Management options like weeds control, sustainable development methods, and control of feral animals.

The workshop discussions brought to light the importance of the research in Kakadu to the implications to the rest of Northern Australia, and in other tropical floodplain river systems worldwide. Development discussions in Northern Australia include water extraction for irrigation schemes, and understanding the hydrology and it’s linkages to fish, food webs, energy, and cultural resources helps predict the possible outcomes under water extraction.

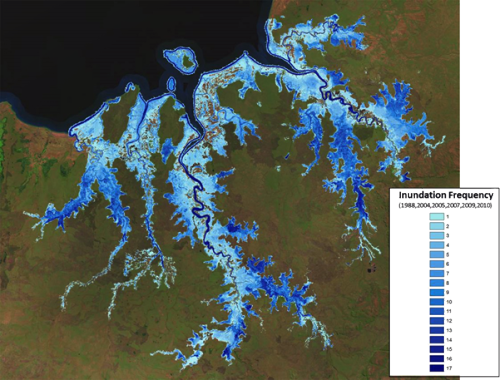

For example, flood and inundation in the North is relatively predictable in timing, but the extent of flooding varies. The rich biodiversity in Kakadu is adapted to these variable flooding conditions, so extracting water in a relatively normal year may not have dramatic consequences. However, extracting water in a low flood year may have dire consequences for the ecosystem. These effects may not be seen until the dry season, when open water refuge areas may be deprived of water normally delivered through the wet season.

![Anbangbang Billabong. Credit: Heath Kelsey [Anbangbang Billabong]](/site/assets/files/2466/anbangbangbillabong-500x333.jpg)

About the author

Heath Kelsey

Heath Kelsey has been with IAN since 2009, as a Science Integrator, Program Manager, and as Director since 2019. His work focuses on helping communities become more engaged in socio-environmental decision making. He has over 15-years of experience in stakeholder engagement, environmental and public health assessment, indicator development, and science communication. He has led numerous ecosystem health and socio-environmental health report card projects globally, in Australia, India, the South Pacific, Africa, and throughout the US. Dr. Kelsey received his MSPH (2000) and PhD (2006) from The University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health. He is a graduate of St Mary’s College of Maryland (1988), and was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Papua New Guinea from 1995-1998.