To Move or Not to Move: Relocating The Chesapeake Bay Program

Bill Dennison ·I recently attended a meeting in Maryland Senator Ben Cardin’s office in the Senate Hart Building. The meeting was with congressional staffers and representatives from a diversity of governmental agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency and the Government Services Administration. The topic of the meeting was the potential relocation of the offices of the Chesapeake Bay Program. The proposed move was to an Environmental Protection Agency building in Fort Meade, a large army base in Maryland, about twenty miles from the current Annapolis facilities.

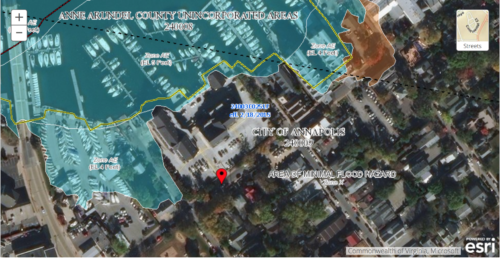

The Chesapeake Bay Program offices have been at 410 Severn St., Annapolis since 1985. When the offices were initially located in this complex in Eastport, Maryland, they were not in the 100-year floodplain. However, revisions of the flood plain have occurred, not surprising given the accelerated rate of relative sea level. Under the Clean Water Act, Section 404, an executive order (11988) was created in 1977 that requires federal facilities to avoid being located in the floodplain. The Federal Emergency Management Agency map of Annapolis shows the 410 Severn Ave. facilities to be largely, if not entirely, in the “Area of Minimal Flood Hazard,” so I am not convinced that this move is warranted solely based on the flooding risk.

The other factor that was discussed was the cost of paying rent by locating the offices in leased space instead of locating on property owned by the institution. This is an issue that I am familiar with in Annapolis, having leased office space for the past fifteen years. There are a couple of considerations that need to be factored into the equation. Leased space means that the upkeep and maintenance (and depreciation) of the facility is a burden of the owner, allowing the organization leasing the property to focus on their core business. Furthermore, the city of Annapolis uses taxes that the owner pays on the property to fund city services, whereas federal or state properties (which are common in Annapolis) do not pay taxes, thus leased properties enhance the city’s ability to provide crucial services. Finally, we have moved several times to different properties in Annapolis, based on our current space and parking needs and desire for co-location with other organizations. Leasing space allowed that flexibility. So, leased space vs. owned considerations are more nuanced than the concept of ‘free rent.’ For these reasons, I believe that there is a false economy associated with moving to owned facilities vs. leased facilities.

A point that I made at the meeting was that the Chesapeake Bay Program with all of its partners is essentially a campus. It is a safe place where collaborative learning takes place, involving many different disciplines. The co-location of different disciplines is important (e.g. fisheries, water quality, monitoring, modeling, communications, land use, remote sensing, geographic information systems) to develop a shared vision and mission. The campus ‘faculty’ are the 20 EPA and 65 other employees who work for various academic and federal institutions. In addition to these full time campus staff, there are roughly 800 people (including me) who regularly attend the various workgroup, goal team, and board meetings. Thus, the 85 ‘faculty’ and 800 ‘students’ constitute the campus. The current campus location is a place that is widely accessible for both ‘faculty’ and ‘students.’ Relocating just the ‘faculty’ to Fort Meade would effectively lose most of the ‘students’ due to access difficulties. Who can imagine a college campus without students?

Another point that I made was that the partnership is working. The partnership involves 6 states plus the District of Columbia, a diversity of federal agencies, various non-governmental organizations and universities. It is much broader and deeper than the 85 employees supported by the Environmental Protection Agency portion of the Chesapeake Bay Program. This partnership has evolved over three decades and is a global model for environmental management. After many years of diagnosing the problems, developing monitoring capabilities to track progress and modeling capacity to predict management outcomes, and instituting both voluntary and regulatory mechanisms to incentivize good environmental stewardship, we are now reaping the results of these efforts. The Chesapeake Bay is actually becoming healthier and more resilient. The aquatic grasses are resurging, the ‘dead zones’ of low oxygen bottom water are shrinking, the fish and shellfish populations are stabilized or improving, and these improvements have recently been linked to the partnership activities that have reduced the loads of sediments and nutrients into the Bay. It is my view that this move would jeopardize this progress, leading me to ask “If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”

The final point I made was that Annapolis is the nexus of activity for Chesapeake Bay management. Annapolis is fairly central within the watershed that includes New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and West Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay Program offices are immediately adjacent to the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office, National Park Service, and U.S. Forest Service. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has an office in Annapolis as well. Many different organizations associated with Chesapeake Bay restoration have chosen to locate in Annapolis. They have chosen Annapolis because they value the co-location of organizations that deal with Chesapeake Bay issues. Many of these organizations have regional offices in Virginia and Pennsylvania, but their central offices are in Annapolis. These organizations include the following: The Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Alliance for Chesapeake Bay, Chesapeake Bay Commission, Chesapeake Bay Trust, Chesapeake Conservancy, Chesapeake Research Consortium, and the Choose Clean Water Coalition. The University System of Maryland has an Annapolis presence, including the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science office, and the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center. Annapolis is the capital of Maryland and various state agencies based in Annapolis are active in the Chesapeake Bay Program, especially Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Moving the Chesapeake Bay Program office away from this nexus does not make sense.

In summary, I can appreciate the need to avoid flooding and to economize on operating costs, which stimulated this discussion. But for the reasons I have outlined; a false economy associated with renting vs. owning, the loss of the campus atmosphere, risking a partnership that is showing real progress, and the co-location of many Annapolis-based Chesapeake organizations, moving the Chesapeake Bay Program office from Annapolis to Fort Meade does not make sense.

Flood map from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Image not protected by copyright.

About the author

Bill Dennison

Dr. Bill Dennison is a Professor of Marine Science and Vice President for Science Application at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.