All about the Bay: Exploring history, heritage, and habitat at the Chesapeake Studies conference

Suzanne Webster ·

Earlier this month, several IAN team members attended the first annual Chesapeake Studies conference. This multidisciplinary conference was hosted at Salisbury University from June 5th to 7th, and was focused on the scholarly study of the Chesapeake region. It was an excellent opportunity for us to meet other Chesapeake Bay researchers, and to showcase some of IAN’s approaches for learning more about the Bay, engaging Bay stakeholders, and communicating Bay science.

The conference opened with an evening reception at the Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art. The reception was a wonderful chance to meet many of the conference organizers and presenters, while dining on some of Maryland’s culinary classics, including hot crab dip and the famous Smith Island cake! I also really enjoyed exploring the museum and admiring the incredibly impressive and intricate painted wooden sculptures of waterfowl, along with an extensive collection of emotive Chesapeake photography.

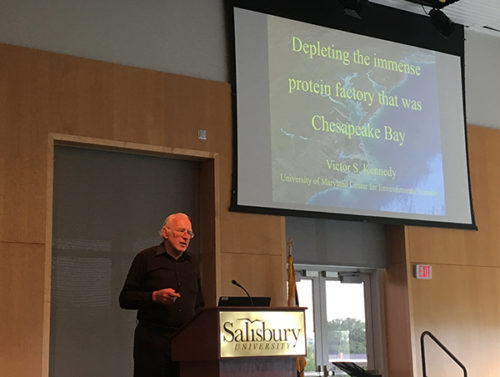

The next morning, UMCES Professor Emeritus Dr. Vic Kennedy delivered an interesting keynote address, during which he told us the stories of the Bay’s oyster and shad fisheries, from both a historical and ecological perspective. His extensive use of archival photographs really helped to paint a picture of the Chesapeake Bay of the past, and, coupled with contemporary environmental monitoring data, illustrated how baselines have shifted dramatically over the last centuries.

The first session I attended was a discussion centered around the Deal Island Peninsula Project (DIPP), which is a long-term, collaborative project that helps empower the community on Deal Island to build socio-ecological resilience to rising water levels and other impacts of climate change. During the session, several DIPP team members shared their individual perspectives on the work they are doing as part of this transdisciplinary effort, and it was very interesting to learn more about the research team’s approach from the points of view of experts in different disciplinary fields and a Deal Island citizen stakeholder. During their talks, the presenters emphasized the importance of slowing down the pace of collaborative efforts in order to build trust amongst contributors, create inclusive spaces for knowledge co-production, and establish a sense of mutual understanding, which they argued is the basis of implementing resolutions and driving behavioral change.

Perhaps in contrast to IAN, the DIPP team emphasized that they do not spend their time thinking about how to effectively communicate knowledge or build consensus. Instead, DIPP chooses to emphasize collaborative learning, community-building, and stakeholder empowerment. Furthermore, their presentation made it clear that their team is extremely deliberate in how they go about reaching these objectives—for instance, they strategically draw from their team member’s multidisciplinary academic expertise and diverse experiences working with stakeholders in different capacities. As IAN increasingly highlights the role of stakeholder engagement in our own projects, it will be exciting to see what our group can learn from other transdisciplinary research teams with different histories and approaches.

Next, we transitioned to our IAN session, during which we highlighted several of the transdisciplinary approaches that IAN uses to help teams collaboratively research the Chesapeake Bay and communicate Bay science to wider audiences. The session featured presentations by IAN employees in the style of lightning talks. Bill and Emily discussed how various science communication techniques, such as crafting descriptive narratives and creating artistic and informative conceptual diagrams, can help transdisciplinary teams conceptualize complex socioecological processes and synthesize a wide range of perceived values and threats to the Bay. Nathan and I highlighted two non-traditional monitoring projects, Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative and Chesapeake Bay SAV Watchers, which engage citizen scientists in generating new knowledge of the Bay and its watershed. Finally, Heath and Vanessa shared insights on the developmental process and stakeholder perceptions of the ongoing expansion of the Chesapeake Bay Report Card.

During the poster session after lunch, I particularly enjoyed speaking with Jen Dindinger, a Watershed Restoration Specialist with Maryland Sea Grant Extension, and a member of DIPP’s coordinating team. Her poster detailed her work with the Watershed Stewards Academy, which is a training program that is designed to empower community members to assess and improve the health of their local waterways. The session following the poster session was also very enjoyable and informative, and the speakers provided insights on different aspects of Chesapeake environment and policy, from a historical perspective. Dr. Andrew Ramey, from the Department of History at Carnegie Mellon University, outlined a timeline of Chesapeake Bay restoration, focusing on the creation of the Chesapeake Bay Agreement. It was very interesting to hear his archival research on how certain historical events related to Bay restoration and management came to fruition, and I am excited to look into his work further for my own dissertation. Finally, the conference concluded with a film screening of “An Island Out of Time,” a short documentary about the unique community of Smith Island, Maryland, and an engaging discussion with the film’s creators.

I was very glad to have seen the video and learned a bit about the cultural heritage and identity of the Smith Island community because the next day, I went on a guided field trip to Smith Island with nine other conference attendees. We visited the town of Ewell in the morning and met with the Island’s pastor, Rev. Everett Landon, to learn more about the local community. Then we had some time to explore the town, take a walk through the marshes, experience the Cultural Center, and visit the enormous Tabernacle where the annual camp meeting takes place. Next, we took a boat to Tylerton, an even smaller town where we were able to enjoy some of the Island’s famous crab cakes and Smith Island cake at Drum Point Market. We spent another hour wandering through the town, during which we visited all of the major sites: the church, the Crabmeat Coop, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Environmental Education Center, and the extensive system of docks where we could see all of the watermen’s fishing gear up close.

The field trip reminded me of how important it is for people to celebrate unique cultures, preserve stories, and empower communities to share and defend their heritage. Learning the story of Smith Island was particularly special for me because it reminded me of a different story that I heard during my first semester in college, about another island off the coast of Ireland. Like the people of Smith Island, residents of Inishark also faced devastating socio-environmental challenges that, in their case, eventually forced the shrinking community to abandon their island altogether. Cultural anthropologists and archaeologists have since worked with local Irish communities to document the story of this diaspora and the heritage of the island community. I have this story to thank for cuing me in to the importance of heritage and piquing my interest in the field of cultural anthropology. In the case of Smith Island, residents continue to fight tirelessly to preserve their island’s culture, as well as its eroding physical landscape.

When sharing the socio-environmental story of a community such as Smith Island, it is very important to acknowledge how aspects of the narrative (such as the way the characters are portrayed and the source of conflict) can change, based on perspective. For example, when resource managers talk about Smith Island, often the topic arises in the context of a larger discussion of climate change and sea level rise, and the island’s residents are painted as nostalgic watermen with admirably (and sometimes frustratingly) high levels of resilience and optimism. Conversely, many island residents tell the story of the demographic collapse of a forgotten people, brought on in large part due to the State’s unwillingness to invest resources into counteracting outside forces like erosion and economic migration. My point in illustrating this difference is this: When we communicate science at IAN, we know that it is good practice to consider all available data and represent scientific results as transparently and objectively as possible. As we begin to communicate more and more often about topics related to socio-environmental issues and human culture, it is imperative that we are equally diligent and mindful when working with people’s stories. Whenever possible, we should look for ways to help others tell their own stories and empower communities to protect their environment.

I really enjoyed attending the Chesapeake Studies

conference. It was great to meet some new people and potential collaborators,

and to reconnect with several others who I don’t often have the opportunity to

see. I walked away from the conference with several new ideas and contacts for

my own research, and I hope that our group at IAN, as a team, also can build

upon some of the approaches and concepts that we learned from other Chesapeake

scholars.

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.