How can we include and legitimize other voices in science?

Suzanne Webster · | Environmental Literacy | Science Communication |Last month I attended the Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences conference at American University in Washington, D.C. from June 20-23. This organization serves scholars who research and teach sustainability and other environmental issues through interdisciplinary lenses, and seeks to advance the "scholarship of science in service to society and the environment." The selected theme of "Inclusion and Legitimacy" was centralized in the conference discourse and culture.

In the opening plenary, keynote speaker Bob Perciasepe reminded conference attendees of the need to legitimize science in society, especially in our current climate where academic knowledge is increasingly challenged by policy makers and members of the public. Perciasepe argued that because the public largely determines to what extent our science will be permitted to serve society, researchers should consider public reception to be another component of the peer review process of science. Public engagement in science is not only a way to increase public buy-in for our research, but the additional diversity of perspectives, quantity and variety of data, and trust between academics and communities allows us to create science that is more actionable, relevant, and acceptable for service to society. In short, in order to legitimize science in society, we must work to include and legitimize other voices in science. This conference community was brimming with ideas for how to do just that:

Diversify whose knowledge and values are incorporated into science

Sustainability scientists, as a community, are often tasked with developing recommendations that protect nature and promote a more sustainable future. When scientists discuss what we, as a society, value about the earth and how we should work to protect these values, they need to include the voices of underserved communities, people of color, children, and indigenous cultures. Including diverse voices in this conversation will allow scientists to co-create science and sustainability solutions that are more creative and representative of the enormous diversity of environmental value systems on our planet.

Include non-scientists in knowledge creation even when they seem "wrong"

Scientists have built an exclusive institution for ourselves, sometimes nicknamed the ivory tower. Environmental scientists have created an environmental narrative that vilifies people by dividing society into those who destroy nature and those who save it. In doing so, we have (unintentionally) delegitimized others' voices and alienated themselves from the rest of society. This strategy was arguably ineffective because many of the people that were not given a seat at the metaphorical table are now controlling the table and deciding how and when science is (or is not) allowed to serve society. Scientists need to build social capital with decision makers and ensure that scientific recommendations represent the best interests of society as a whole.

Legitimize environmental problems that are defined by the public

It is not sufficient to just invite other stakeholders to participate in research or offer input into science; rather, community partners and other non-academic stakeholders should have some degree of decision-making power and influence over what problems scientists research. Elizabeth Beattie argued that if environmental science is to truly serve society, scientists need to "be prepared to give up some power and privilege" for determining "what the science is about" and instead use our resources to support communities in researching issues that are important to them. An example that arose repeatedly during the conference was the Flint water crisis. If scientists had listened to communities and legitimized their concerns from the start, the environmental injustice could have been addressed much earlier and more effectively.

Start global conversations to reach global solutions

The "quick fix" age in sustainability science is fading away. Science and society have made a great deal of progress solving smaller-scale problems like sewage treatment and factory pollution, and environmental legislation often dictates that new development and facilities be built using state-of-the-art technology. Many of our most pressing environmental problems are global and require global consensus and action to make substantial large-scale progress. As scientists, our priority needs to be to inform and engage public officials around the world in order to ensure that future policy decisions are science-based and sustainability-driven.

Interest and engage citizens and students in environmental public policy

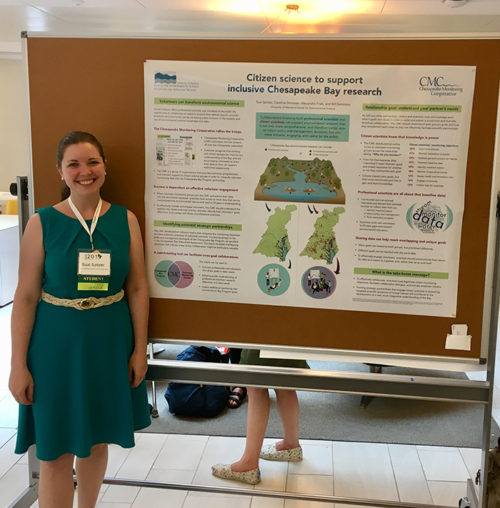

If we want science to inform decision making and policy, we need to empower citizens to use science to fight for their environment. Scientists should support and encourage citizen science groups to generate environmental data and then use it to advocate for environmental policy changes that protect their communities and natural resources. Maya van Rossum and David Wood encouraged us to also think beyond environmental laws and consider environmental protection as a right, and to teach this ethic and expectation in classrooms.

Communicate science strategically to promote science engagement and environmental literacy

We need to frame our research in ways that allow people to connect with our main message. To do this, we should use words, images, and stories that not only interest others, but resonate with their core values and speak to their worldviews and personal experiences. Perciasepe suggested that altering our vocabulary slightly and "engaging people on their terms" can open doors to communicating with certain audiences about polarizing complex issues (e.g. calling climate change "public health"). He also named IAN's Chesapeake Bay Report Card as an example of a science product that effectively increases science engagement and literacy by making environmental issues real at a local level.

Merge scientific data with narratives and visualizations to make science stories more salient

We can legitimize people's personal experiences of complex environmental issues, such as food insecurity and climate change, by incorporating stories from individuals and communities into science data visualizations. Dr. Sonia Stephens and Dr. Daniel Richards shared an excellent example of this kind of integration with their esri Story Map, which combines maps of sea level rise projections with stories and images from residents of coastal areas in order to explain climate change on a more personal level.

Harness the power of emotional communication through art, music, and place

Scientists should actively create opportunities for people to learn about their environment and develop a conservation ethic. We need to hook people into caring about the science of the environment by first getting them to connect with the environment itself. Science dialogue is not always the most effective way to do this. Sometimes art and music can help scientists intrigue their audiences and communicate the essence of a scientific concept. Other times, the best way to deepen this connection between people and environment might be to create opportunities for people to interact with place, itself. For example, Lissy Goralnik showed how interactive nature trails can promote environmental caring and learning, and Dr. James Mills argued that environmental pilgrimage routes could provide a spiritual commons for those who want to deepen their connection with nature.

Finally, rally devotion to the natural world by first rallying devotion to communities

Scientists need to stop communicating about the environment in ways that suggest that humans are not, or should not be, a part of it. Courtney Carlson urged us to advocate for a more inclusive understanding of the environment as being broader than just the natural world. Our environment includes ourselves, other humans, and the "built world," such as schools and homes. People need to see themselves and their communities as intimately connected to the natural world, rather than excluded from it, if they are going to commit themselves to caring for it.

All in all, the AESS conference was a very positive, eye-opening experience. I appreciated that every speaker contributed something to this important discussion of increasing diversity and inclusivity in environmental science, and I am excited to incorporate some of these ideas into my own research.

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.