Uncovering five values of citizen science at CitSci2019

Suzanne Webster ·

Last month, Caroline, Alex, and I attended the Citizen Science Association (CSA) conference, CitSci2019, from March 13-16th in Raleigh, North Carolina. This conference was a great opportunity for us to learn more about what is happening in the field of citizen science, network with other professionals, and share updates on some of the projects that we are involved in at IAN.

This was my second time attending the CSA conference, and I noticed again that this conference community has an underlying culture unlike many others. For example, attendees seem to be especially well-connected, notably ‘artsy,’ and particularly focused on making others feel included. In 2017, one of my mentors helped ease my anxieties about giving my first presentation by assuring me that I “could not present to a friendlier audience”. As I reviewed my conference materials in preparation to write this blog, five major themes emerged from my notes on both the session content, as well as the organization of the conference. I think of these themes as five distinct values of this conference community, and of citizen science, more broadly. Funnily enough, I discovered that CSA has already specified five values of their organization, and several of these overlap with the five themes I pulled from the conference! In this blog, I will share some thoughts on my conference experience, using my own version of the five values of citizen science as a guiding framework.

1. Connectivity

The theme of CitSci2019 was “Growing our family tree”. There was a lot of deliberate discussion throughout the conference about how citizen science researchers and practitioners must continue to build tools and share resources that allow the broader citizen science community to build lasting, fulfilling, and productive partnerships. For example, Caren Cooper discussed how meta-platforms can help foster collaboration between distinct citizen science projects, facilitate research on the science of citizen science, and guide volunteers as they engage in a “landscape” or “ecosystem” of projects. Caroline Donovan led a roundtable discussion to provide guidance for how to form a regional partnership, like the Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative, which links together citizen science initiatives in the same areas and builds partnerships between volunteer monitors, academic institutions, and government agencies. During his talk Bill Zoellick emphasized the importance of supporting local science capacity by connecting community institutions, activating local resources, and building strong networks of practitioners who can sustain community science projects without having to rely on academic scientists. The conference also kicked off with a morning networking session, and provided many opportunities for me to reconnect with one of my academic mentors, Dr. Andrea Wiggins, as well as some colleagues at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and the University of Maryland iSchool.

2. Creativity

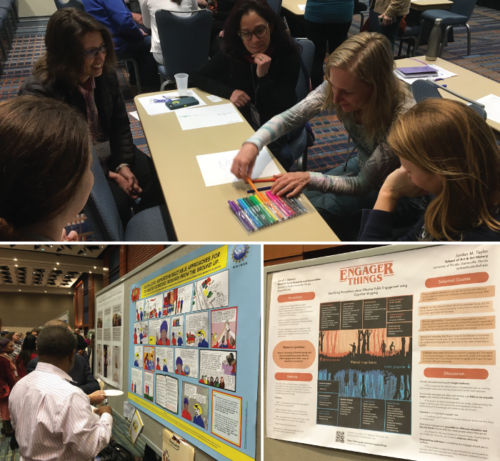

There was a clear emphasis on art, imagination, and creativity throughout the conference sessions and social events. The poster session was full of visually-appealing posters, many of which cleverly incorporated design elements that are not traditionally found at academic conferences, such as pop-culture references, memes, and comic strip art. Several workshops were offered on diverse topics such as storytelling, science communication, and improvisation theater. Alex, Caroline, and I presented a workshop called “Best practices of Science Communication,” which taught attendees how to communicate scientific concepts to targeted audiences by investing time in writing active titles, and creating compelling and informative graphics, such as conceptual diagrams.

It was also very clear that the conference organizers put quite a bit of effort into planning the evening events, in particular. The conference opening reception was hosted at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. It was fun to explore the interesting and interactive museum exhibits (especially the hands-on Naturalist Center), listen to a live band and project slams in the three-story globe-shaped SECU Daily Planet theatre, and learn more about ongoing citizen science projects and other research efforts in the Museum’s research labs. The second evening of the conference was an IMAX movie night featuring the new film, “Backyard Wilderness,” about the importance of exploring the natural world around us and forming connections to Nature. The film was artistic and relatable, and it motivated me to get outdoors more (In fact, I am writing this blog outside right now!). The movie screening was followed by a reception and panel discussion with the creators of the film, and it was interesting to learn more about their inspiration behind the film and the process of creating it, while enjoying beautiful nature-themed cocktails and desserts!

Whether through museum exhibits, film, or food, the

emphasis on showcasing different forms of imaginative and nature-inspired art

contributed to my overall conference experience, making me smile, re-energizing

me for more listening and learning throughout the conference sessions, and

inspiring me to put that level of care and creativity into my own work. Beyond

the conference, itself, the city of Raleigh also provided some creative

inspiration. We enjoyed exploring the downtown area and admiring the colorful

murals and other public art.

3. Diversity

The citizen science community is growing more diverse

every day, and this diversity was also reflected at the CSA conference, itself.

Conference attendees included elementary school teachers, project coordinators

and Waterkeepers, citizen scientists, academics from different disciplinary

homes, and more. Attendees also represented a wide diversity of countries,

cultures, and ethnicities. Just from this conference, it was clear that the CSA

community embraces diversity and is eager to take deliberate actions to make

everyone feel welcome and included.

For example, every conference attendee was invited to provide their preferred pronouns during registration, and these were included on the nametags that we wore all week. I thought the conference organizers did a lot to promote the visibility and acceptance of the LGBTQ community. Perhaps in light of the decision to relocated the CSA meeting after the “bathroom bill” (HB2) was passed in 2017, there was a particular emphasis on recognizing the transgender community at CitSci2019, with informative workshops, roundtable discussions, and other conversations focused on transgender equity dispersed throughout the program. Finally, there was also a written code of conduct for the conference, which specified expectations for interactions between all conference attendees in a push to “ensure a positive, equitable and open culture”.

This year, there was also a targeted emphasis on the topic of environmental justice (EJ). In fact, EJ was one of the three major conference tracks this year, which was fitting given that North Carolina is the birthplace of the environmental justice movement. Many workshops and sessions specifically addressed the intersection of EJ and citizen science, highlighting citizen science projects that involve and benefit indigenous communities, at-risk rural populations, and other underserved groups. Conference organizers also offered a field trip to tour important EJ sites outside of Raleigh, as well as a scholarship for people who are engaged in citizen science efforts that promote EJ. Furthermore, the Environmental Justice and Community Science panel discussion on Friday evening presented an excellent opportunity to learn about some of the successes, challenges, and best practices associated with community-driven research that addresses EJ issues.

4. Equity

Equity, according to Max Liboiron, is the idea that we should be sensitive to the fact that people enter into situations from different positions (social, economic, political, historical, etc.), and we should acknowledge and address the causes of these differences in our research. Equity is not the same as equality, which involves treating everyone the same, regardless of their starting position. In order to promote equity in citizen science, all participants must acknowledge their privilege, and be aware of how it causes them to experience life differently from others. During her keynote presentation, Max provided an example of this process, saying that sometimes scientists enter into a research partnership with the upper hand (more direct access to funding, control over research questions, increased credibility in a political context, etc.), whereas other times scientists are the ones at a disadvantage because our privilege effectively blocks us from being able to form certain relationships or “see and know certain things”.

Equity can transform power relations in collaborative

work. Max also encouraged us all to continuously question our subconscious

conceptualizations of who or what is normal (powerful), and by contrast,

abnormal (lesser). For example, to promote equity in citizen science, we should

abandon the “deficit model” of viewing citizen scientists as “undercooked

scientists”. That is, we should stop continuously comparing citizen scientists

with professional scientists, and asking “Why is this person that’s not like

me, not like me?” Similarly, we should stop conceptualizing citizen science as

a lesser form of “real” science. We should stop thinking about traditional

science as the default, or normal, privileged model, and instead start viewing

science as one piece of the puzzle or one tool in the toolbox. We should

recognize that citizen science is totally distinct from traditional science,

with its own unique set of contributions, assets, and challenges. And finally,

we should focus our attention on creating equitable citizen science

opportunities that explore concepts and phenomena from multiple perspectives,

keep everyone engaged throughout the process, offer support and ample access to

necessary resources, and make space for sharing knowledge and ideas.

5. Advocacy

Scientists often devote years, or even entire careers, towards researching phenomena that spark passion or interest on a personal level, without necessarily thinking about how their research could (or should) make a difference to society. Furthermore, in the world of academia, especially in the natural sciences, scientists also often shy away from being known as an advocate out of fear that their research will be labelled as biased or lacking objectivity. Citizen science, by contrast, frequently breaks this tradition. Max Liboiron reminded the audience that “As soon as you do any science, you are making a political statement” because the choices we make throughout the scientific process (where you get grants, who you work with, etc.) reproduce our own values. Dr. Sacoby Wilson also urged conference attendees to never shy away from serving as an advocate. He said that his lived experience inspired him to become an environmental scientist, and he takes pride in the fact that his research builds communities and leads to environmental change. He also said “Science, alone, does not promote action” most of the time. Instead, we need a combination of science and advocacy, as well as a political strategy, in order to truly impact decision making and policy.

Both speakers had a clear message: Doing scientific research is personal, and the work that researchers do is a direct reflection of our values as scientists. Not only that, but as researchers, it is our responsibility to do work that does not purely satisfy our own personal curiosity, but that also leads to real and significant change for the environment and society. Citizen science allows us to take this one step further, and do research “for the community and by the community,” which gives people the power to use science to make a difference in their own lives.

CitSci 2019 was a productive and thought-provoking conference. I am inspired to try to incorporate these five values— connectivity, creativity, diversity, equity, and advocacy— into all of my future work in the field of citizen science.

About the author

Suzanne Webster

Suzi Webster is a PhD Candidate at UMCES. Suzi's dissertation research investigates stakeholder perspectives on how citizen science can contribute to scientific research that informs collaborative and innovative environmental management decisions. Her work provides evidence-based recommendations for expanded public engagement in environmental science and management in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Suzi is currently a Knauss Marine Policy Fellow, and she works in NOAA’s Technology Partnerships Office as their first Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Specialist.

Previously, Suzi worked as a Graduate Assistant at IAN for six years. During her time at IAN, she contributed to various communications products, led an effort to create a citizen science monitoring program, and assisted in developing and teaching a variety of graduate- and professional-level courses relating to environmental management, science communication, and interdisciplinary environmental research. Before joining IAN, Suzi worked as a research assistant at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA and received a B.S. in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Notre Dame.